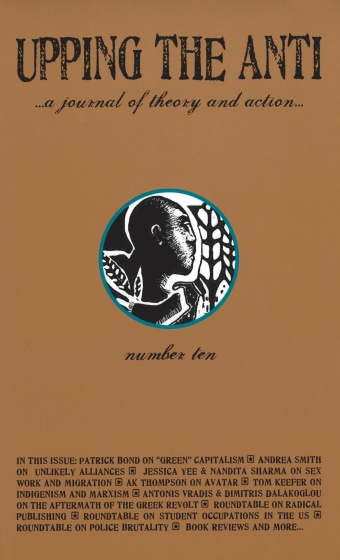

No Justice, No Peace!: A Roundtable with Ex-Cops on Resisting Police Repression

When Montreal police officer Jean-Loup Lapointe shot Fredy Villanueva to death on August 9, 2008, riots erupted, making headlines throughout the world. Montreal activists have organized against police violence and impunity for years, but the campaign stemming from Fredy’s killing caught mainstream attention and compelled many people to scrutinize the police. This high-profile case reset the stage, in Montreal and elsewhere, to challenge the prevailing belief in the sanctity of police institutions and their defense of police officers’ discretion in the use of force.

Anti-police brutality activists aim to reveal the oppressive function of the police – to show that racial and social profiling as well as police brutality are logical extensions of institutionalized systems of violence and repression. In this work, we can learn a lot from police officers who have left the force for political reasons. If we hope to de-mystify and de-legitimize oppressive institutions, it is valuable to dialogue with people who joined the police force because they believed it was a means for constructive social change and left because they discovered it is not.

Some people not only leave the police, but also become active in social justice movements. It’s important for movements to both recognize the humanity of such individuals while they were part of the police and the contributions they have made to various struggles since leaving the force. Their insights can inform anti-police recruitment and anti-police brutality work, as well as initiatives that focus on other institutions of state repression and imperialism, such as security-intelligence agencies and the military. In this roundtable, three former police trainees (two of whom worked as officers) share their experiences and perspectives about policing institutions, offer their ideas about how to oppose and eliminate police violence, and discuss the possibilities of building a society without police.

This roundtable originated with the Forum Against Police Violence and Impunity,1 held in January 2010 in Montreal. Over three hundred participants explored a range of themes, including: asserting oneself when dealing with the police, police repression of social movements, youth and profiling, profiling of drug users, campaigns for justice led by family members of people killed by the police, gender and police violence, and working toward justice without police. The opening panel featured Montreal-based activists Gaby Pedicelli, Marcel Sévigny, and Will Prosper, all of whom agreed to continue their discussion in the pages of UTA.

Gaby Pedicelli completed the police technology program at John Abbott CEGEP and the Nicolet police academy in the late 1980s, but never worked as a police officer because she very quickly became critical of police culture. She wrote the book When Police Kill: Police Use of Force in Montreal and Toronto, published in 1998. Gaby works at the People’s Potato (Concordia University’s vegetarian soup kitchen) and is active in prisoner support work with people serving life sentences.

Marcel Sévigny worked with the Montreal police force for almost nine years in the 1960s and 1970s. He eventually quit because of concerns that he would waste his life. He went on to work and organize in the community sector, and was a municipal councilor for 15 years in the neighbourhood of Pointe St-Charles. Marcel identifies as an anti-authoritarian, and is currently active with groups like La Pointe Libertaire and the Autonomous Social Centre. He published his second book: Et nous serions paresseux? Résistance populaire et autogestion libertaire in 2009. His answers in this text were translated from French.

Will Prosper joined the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) while in university, and worked in Manitoba for five years. Since the shooting death of Fredy Villanueva, he has been actively involved in anti-police brutality organizing in Montreal-North with Montréal-Nord Républik, and was involved in the organization of Hoodstock, a social forum and urban musical event, held in Montreal-North this past summer.

What is the police acculturation process? How do age, sexuality, race, ability, class, and gender inform this process?

Marcel: Some things have changed since I trained in the 1960s and 1970s. Police work has become professionalized, and the training is longer. But much of it remains the same. The police force is still regularly presented as distinct from, or opposed to, civil society – “civilians versus us, the police.” This distinction is used to ward off subversive or dissident ideas that could undermine the police force and imperil state institutions, as occurred with the police strike of 1969.2 In my time, we were constantly reminded that three subjects were taboo and not to be discussed: women, religion and politics. This was part of the acculturation process; it reinforced the false separation between the police force and civil society. To this day, this belief leads police to behave arrogantly and use their authority to intimidate people, especially people who do not trust the system. This distinction also favors the development of an esprit de corps (“gang mentality”) that ensures that the police remain immune from internal criticism, even if egregious mistakes are committed.

In my time, police officers received no sensitivity training about issues of social justice. Officers’ prejudices came out while on duty, including those against women, racialized people, and Quebec nationalists (who were considered a minority that had to be surveilled). Interestingly, homeless people were not actually the target of any specific repression at the time; in fact, it would not be unheard of for police officers to bring food to homeless people who slept on park benches. This situation has changed significantly since homeless people are now considered a menace to the social order.

Will: I trained in Regina about ten years ago. When I entered the academy, it was clear right away that it had a para-military quality. For example, we would have drills every morning. For a detached shirt button you would receive a penalty. Beds had to be made every morning. These rules served the purpose of breaking down cadets. New recruits would fall in line and quickly become part of the machine; cadets and junior officers learned to defer to pre-established rules and superiors’ orders.

I was different not only because of the colour of my skin but also because of my attitude and the way I dressed. There were certain things I didn’t want to change about myself. I had dreadlocks at the time; I told myself that if women in the force could have long hair, then I should be allowed to have long hair as well. My attitude didn’t sit well with everyone.

Gaby: People often decide to join the police because it is a good paying job with minimal education requirements; what other job offers a $40,000 salary, good benefits and a strong union that will defend you unconditionally? This attractive offer is strategic, because the policing institution is based on the military model whereby cadets, through their training, are stripped of their individuality. One of the many problems with the acculturation process is that officers usually begin working at the age of 21. It is beneficial for the policing institution for new recruits to be young and lacking in life experience, as they are more likely to follow prescribed methods. Training prepares them to accept orders without question and to respond to potentially stressful situations without emotion. Being young and being given so much responsibility, discretion and power – the right to carry a firearm and determine how persons should conduct themselves – often results in panicked and extreme responses and abuses, whether deliberate or not.

Policing is associated with physical force and has historically been a domain dominated by men. This informs gender dynamics within the institution. Women are encouraged to adopt ‘macho’ behaviors, and often do so in order to feel accepted by their male colleagues. The risk of being stereotyped as ‘emotional’ compels women to be hard-lined while on duty. Police culture is also very heteronormative; to avoid harassment, officers who are not heterosexual often remain closeted.

Many police forces strive to hire “visible minorities” to avoid accusations of systemic racism. They use these few as “poster boys,” placing them in ad campaigns and encouraging them to take on speaking engagements. They also often use these individuals to infiltrate their own communities.

The police do not hire persons with limited mobility or mental health issues. My entry into the police technology program was dependent upon a complete physical examination by a general doctor and a series of psychological exams. The exclusion of persons with disabilities is based on the assumption that use of force is always a possibility, even though many situations require only verbal mediation. This reinforces stigmas about physical disability and mental health, which then informs officers’ irrational and extreme responses, particularly when they encounter individuals with mental health issues.

The acculturation process indoctrinates new officers into certain views of the world and its “criminals.” Those on the fringe quickly find out that in order to assimilate, they must strip themselves of all personal convictions. Otherwise, the only option is to leave the force.

Are there parallels between the police force and the military in Canada? Is the local role of the police similar to the international role of the military?

Gaby: The military and the police are similar in many ways. Both institutions train with the goal of stripping persons of their individuality so they will unquestioningly follow orders, and neither institution values personal input or experience much. Training involves hazing rituals and rigorous physical activity aimed at breaking individuals down. Cadets at the academy, like in the military, are lined up to be berated and shouted at by their superiors for trivial things (boots not properly shined, creases on a shirt, etc.). Subservience is required – “yes, Sir!” – and talking back is unacceptable. Hazing is conducted in order to ensure that each person knows their place as a cog in the machine.

Like the military, the police serve the needs of those in power. After September 11, 2001, the police began a campaign of random detentions and interrogations, targeting members of Arab and Muslim communities. Laws were enacted to foster more police discretion. The police are fighting the ‘war on terror’ at home while the military fights it abroad. Once again a particular segment of the population was targeted in the name of public safety.

Will: The police and military complement each other, and their trainings are comparable at nearly all levels. When countries are in a ‘crisis’, the two work hand-in-hand. Moreover, they are both on the payroll of the government.

Marcel: There are differences between these two institutions (for example, in Montreal, the population has greater contact with its police than with the military), but they are part of the same system of “law and order.” Both try to uphold positive public service images to camouflage their actual social role: to maintain order through repression. If the two bodies are called to collaborate on the ground, a hierarchy stipulates that the military can control the police in case of crisis, and can replace the police force if necessary. This hierarchy creates distrust between the two institutions.

In comparison to the military, a local police force often walks on eggshells. Police blunders may be more easily denounced since police are in direct contact with the communities they “protect and serve.” When the military acts in another country, since it is intervening in an unfamiliar setting, soldiers assume that their presence confirms the inferiority of the local population. Oftentimes, civil society in these places is already suffering from significant repression, so monitoring a foreign military’s actions is more difficult. It is during moments of social tension that similarities between the police and the military are most obvious.

Some people join the police with good intentions. How are these people assimilated into police culture upon entering the force?

Will: In my experience, the majority of people who join the police do so with good and honest intentions, and most of them believe they will make a difference in the community they serve. One of the biggest problems for new police officers is hierarchy within the force. New officers with good ideas are rapidly shut down by the old guard, which perpetuates a repressive policing approach.

Gaby: Many well-intentioned people join the police force with the hope of making the world a better place. That is where I found myself as a 17-year old who was disgruntled with the police. I thought I could be a “good cop” who was compassionate and “human.” I realized quickly that this was impossible. From the beginning of training, the crime-fighting model of policing was instilled. Theft of private property was focused upon without exploring class or race issues. The cowboy attitudes of instructors and students (who could not wait to get out there and find some “criminals”) further convinced me that my initial reason for joining the police would never be realized. This cowboy sentiment was even more pronounced at the training academy. I would either have to go along with the others or branch out on my own and be ostracized by my co-workers. Not only is branching out difficult, it is also dangerous because it means that you will be on your own and can be sabotaged on the job. On that next call you may not get the backup you request. So, your only option is to leave the force.

Marcel: Many police officers who have humanist tendencies will avoid putting themselves in extreme situations; they will avoid joining units that engage in on-the-ground repression on a regular basis. Police officers with a ‘non-violent’ approach to on-duty interventions are often faced with internal contradictions. For example, in the ongoing public inquiry into the death of Fredy Villanueva, based on officer Stéphanie Pilotte’s testimony, it seems that she would not have intervened in a public park the way her partner, Jean-Loup Lapointe, did.3 However, once Lapointe initiated his intervention, Pilotte felt compelled to follow his lead, presumably motivated by a sense of solidarity, deferring to the aforementioned esprit de corps. In situations like these, prejudiced perspectives win out.

What kind of strategies can our movements adopt to exploit the contradictions of the police acculturation process? How can we encourage people to leave institutions like the police and get involved in social justice movements? Should it be a priority for anti-police brutality activists to get people to leave the police?

Gaby: We can continue to emphasize that police exist to enforce submission to all forms of inequality (based on race, gender, sexuality, class) and to quash social justice movements. Officers are the front-line tools used to achieve these ends. The policing institution is an economic extension of the state and was created to force vulnerable people to accept their disenfranchisement. Policing is perfectly consistent with capitalism: the rich get richer and the poor get prison. Important strategies that focus on educating the public must acknowledge this capitalist paradigm.

It is very difficult to encourage people to leave the police; they join because they believe in the institution’s legitimacy. It is true that repeated exposure to systemic police abuses is disenchanting for some, but most officers normalize and legitimize these abuses. The longer an officer works in the force, the more they become immersed in police culture and all its preconceived definitions of crime and criminals.

When I was in the police technology program, I hung out with someone who also did not quite fit in with the rest of the cadets. We often spoke of the contradictions and struggles that we would later face if we joined the police force. She later moved to Ottawa and became a police officer. We continued to debate the systemic problems of policing. She was well aware of the abuses but did not consider herself part of that culture. She considered herself a “good” cop among “bad” cops. Four years later, she had married a fellow police officer and her demeanor and outlook on crime and policing had completely changed. She started defending racial profiling; she said that members of certain communities were more likely to commit crimes and were more dangerous. We argued over this assertion (and others) and ultimately realized we were no longer able to be friends.

It should be a priority for anti-police brutality activists to discourage people from joining the police in the first place. We must focus our efforts on discouraging youth (in high schools and the police academy) from joining the force, before they become immersed in police culture. We should offer workshops outlining the inherent contradictions and systemic flaws in policing. I believe that many people who want to become police officers are not aware of the group mentality and codes of silence that come with the uniform. Several years ago, I gave two presentations on police brutality in a class called “Race and Ethnic Relations” for police technology students at John Abbott College. The professor, who was not part of the police technology program, thought it would be fruitful for students to be exposed to a critical perspective about police abuses. The lecture was about civilian deaths caused by police, which I had investigated in my book When Police Kill. The first class of about fifty students aggressively debated with me. However, the circumstances of many of the deaths were so blatantly unwarranted that all they could point to was the “bad apple” theory. I focused a large part of the talk on the Montreal Police Brotherhood – an entity foreign to most of the students – and the fact that the alleged “good” cops were abiding by the code of silence by not speaking out against the abuses.

I told the class that they would have to toe the line with the rest of the force. It was obvious that they did not have an accurate picture of what they were getting into. After the class, two students approached me in shock and said they would reconsider becoming police due to this “gang mentality.” The next day I gave a lecture to 50 new students, and the students who were there the previous day returned to continue the debate. The students didn’t dismiss my arguments, but came to inquire and engage. Although the professor valued my presentations, I was later notified that my lectures caused havoc in the police technology department; I was not invited to lecture there again.

I believe that we should pursue these types of initiatives that counter police recruiting and expose abuses. The problem with this strategy is the lack of access. Both high schools and CEGEPs will usually not allow activists to conduct workshops that are critical of the police. Community centres may be easier to access, especially those that fall victim to police harassment on a daily basis. We need to get creative in packaging such workshops.

Marcel: It really is a small minority of police officers who will have a radical critique of the police. Most officers who leave the force and want to get involved in society will likely try to do so by focusing their efforts on improving the role of the police and by trying to encourage police collaboration with different groups. I think movements that critique the police as a repressive institution can bring together people who have left the police force and together they can analyze the force’s organizational structure and strategies of repression.

I don’t think getting people to leave the police should be a priority for anti-police brutality activists. On the other hand, it is important to keep in mind that there will always be officers who leave the police on their own initiative. It is a good idea to reach out to these individuals, who may share our perspectives and could offer their “expertise,” although the possibility of infiltration arises.

Will: We need to address what kind of education youth are getting before they join the police. Schools don’t address racial and social profiling, police repression and brutality, or their negative impacts. It’s important for social justice movements to inform the population through grassroots organizing – through protest, social forums, flyers and other means – as this is the only way to sensitize the population, including police, to these realities.

Leaving the police force is a personal choice. An important question to grapple with is: do we really want to encourage a police officer to quit the police to join a social justice movement? Would that police officer have more impact to change policies within or outside of the force? And if that person leaves the police, will they simply be replaced by a more extreme police officer? The police is part of our society, whether we like it or not. This is why it is useful to have a roundtable like this one that encourages us to re-think the role of the police and their mandate. Hopefully, we will open up the discussion and start to question the role of policing itself.

Given the emphasis on security culture in activist circles, is it difficult for people leaving institutions like the police to become involved in social justice movements? If so, how do we deal with valid concerns of our movements being co-opted and infiltrated while also remaining open to people who genuinely wish to get involved?

Marcel: Police surveillance of radical social and political move-ments is standard practice. In the 1960s and 1970s, Quebec nationalists and far-left political and cultural groups were mainly targeted for their involvement in various social movements (including childcare, housing and food-security initiatives). When I left the police force in 1975, I was already an activist. I got involved with social justice movements and adopted an open and transparent attitude. I never hid my past as a cop and made an extra effort to ensure that as many people as possible knew about this past.

These days, police surveillance has expanded to other areas, even within organizations that are relatively well integrated in the power structure. In the 1960s and 1970s, we saw the growth of grassroots protest movements. Through the 1980s and 1990s, these movements reached larger segments of society, but became depoliticized along the way. In the 1980s, the police started liaising with community organizations, joined coalitions and even created police action committees in certain communities. The influence of the community sector’s collaboration with the police is obvious; there is a respect for “law and order,” while activists and other “social agitators” – those who are wary of social control and organize for social change – are considered “de-stabilizing” elements. Some people involved in social movements ultimately end up acting, whether intentionally or not, as tools of surveillance for the benefit of the police within local communities.

In the last ten to twelve years, radical activists and anti-authoritarians have been involved with all kinds of struggles, including issues related to globalization, immigrants and refugees, political ecology, and Indigenous peoples. Meanwhile, the security apparatus has become more aggressive, commensurate with restrictive governmental policies. It attempts to infiltrate activist networks to better surveil them. We should avoid becoming

paranoid but remain conscious of the fact that the police gather information to learn more about activists’ motivations and strategies, and that it is willing to use instigation to fulfill its goals. Activists should thus strive to be as open and public as possible from the get-go. For example, the “autonomous” community sector in Montreal is the most politicized within the community sector. Autonomous neighbourhood groups and committees (where police and other state representatives are not invited) can have open discussions about issues relevant to their neighbourhoods, including the role and actions of the police. Through these neighbourhood committees, activists and organizers who face police presence can share information more easily. It also becomes possible to discuss actions and/or pressure tactics that involve breaking the law (civil disobedience, office occupations of elected officials, etc.).

Finally, we should organize ourselves as part of affinity groups to develop a stronger rapport between us. For organizers who are more “specialized” and involved in work on issues where police repression regularly comes up (like racial and social profiling, sex work, etc.), it becomes necessary to adopt organizing structures that are more closed in order to be able to effectively challenge a powerful institution like the police. The affinity group or network requires a strong internal cohesion both ideologically vis-à-vis the role and actions of police, and a common understanding of the means to combat police repression. Affinities with respect to people’s personalities and behaviors are important to foster a trusting environment among organizers who end up building friendships through their work. This also helps minimize the risk of being infiltrated.

Will: Some people were skeptical of me because I used to be a police officer, but this never offended me. We have to be very careful about police infiltrating social justice movements. But, at the same time, it’s difficult to deny access to a person who genuinely wants to be part of these movements. We just have to limit the information we give them. It is important to remain conscious and vigilant about the possibility of infiltration and that we act accordingly, in line with our politics. There’s no special recipe or clear-cut guideline to deal with this kind of problem. That’s probably for the best because would-be infiltrators will probably read this roundtable!

Gaby: Persons leaving the policing institutions and wanting to join social justice movements should expect to encounter skepticism. They were part of a corrupt system they now want to fight against. Groups should be leery of a new person with a policing background who wants to get involved, especially because there is always the possibility of infiltration. Only over time and through action can ex-cops prove themselves. Initially, a group should not divulge all the information surrounding a particular cause until they are more certain that infiltration or co-optation is not the intention. If the ex-cop remains active with the cause, trust will eventually grow.

What strategies can we use to chip away at the legitimacy people accord institutions like the police, so that

individuals and communities are able to achieve self-determination without state interference?

Marcel: When we speak about strategies, we should distinguish between the violence institutionalized by the state (i.e., main-tenance of poverty, repressive legislation, etc.) and the violence produced by the police who – through the use of dissuasion, intimidation and gratuitous violence – are mandated to contain the anger of those who suffer and experience repression. Fighting against state violence implies simultaneously fighting against those who safeguard the status quo of state violence.

There are many groups and organizations who do not view the police favorably and who mistrust the security forces precisely because of the constant police presence on the ground, where realities of racial and social profiling play out. Those sectors of the population that are the most vulnerable, are the most dispossessed and have the least resources to self-organize for all kinds of reasons (e.g., migrants, Indigenous people, homeless people, sex workers), are the most likely to encounter police intimidation and humiliation. This ends up being fertile ground for the expression of social and racial prejudices. This reality, however, has also allowed for a more distinctive resistance movement to take shape.

The criminalization of social movements must be interpreted as a declaration of low-intensity warfare, where we find ourselves part of a police state. In order to challenge this, we must strive to weaken the credibility of the police. We have to highlight the police force’s repression of social movements, which they justify via a panoply of social- and security-based excuses. How can we do this? Our main strength is solidarity. Together, within our various organizations, we must learn to monitor the police: we should reinforce cop-watch committees, make links and circulate information; we should organize demonstrations in front of police stations, confront politicians about police actions; do systematic poster runs in our neighbourhoods to let people know about what the police are doing; file complaints and go public with these complaints.

The goal of this approach is not to improve the functioning of the police force, even though our efforts might lead to reform in some cases. Rather, the goal is to develop a critique of the system of repression while developing alternatives to the police.

Gaby: A very effective way to undermine the legitimacy of modern policing is to highlight that it is a relatively new phenomenon, created in the middle of the 19th century in Britain and the US. It arose as a strategy for quashing working class struggles that emerged as a result of rapid industrialization and urbanization. As people began resisting their new factory and unskilled labor conditions, a police force was established to stop the rebellions through force; modern police forces were created to help wealthy factory owners. In the United States and Canada, the initial need for policing also evolved from the realities of racism, slavery, and colonial conquest. The RCMP, the national Canadian symbol, was established to aid in the acquisition of the resource-rich land of the Indigenous communities of Western Canada. They took over this land by force and handed it over to the settlers who planned to ‘open up’ the west and build a transcontinental railway. Given that the institution of policing is founded on corrupt capitalist roots over the last 150 years or so, why should we not assume that they continue to exist in order to serve an elite minority at the expense of the majority?

Another possible strategy to decrease police legitimacy is to keep the abuses and the complete lack of accountability at the forefront of the debate. We need to demand accountability from the mass media at every turn. The police are workers of the state and are afforded privileges and power the rest of us do not get. I believe they should be held to a higher standard than the average person. In cases like that of Martin Suazo (killed on May 31, 1995 by Montreal police), in which the officer reacted excessively and without conscience – Suazo was shot in the head and killed while he was already arrested and on his knees with his hands handcuffed behind his back, after shoplifting a pair of jeans – there is no justification. How can people trust that this officer will not be a danger to society and shoot someone else? He should have been fired immediately. Instead, there was a media ban preventing his name from being published so that we did not even know who he was! When an officer steps out of line and shoots someone or decides to engage in a chase and runs someone over, our lives are at risk; the police should be held accountable just like the rest of us would be or, at the very least, be fired.

Instead, officers involved in abuses benefit from the complicity of their colleagues and are investigated by other police officers. If and when they get criminally charged (an exceedingly rare occurrence), they are tried in the same court where they are usually the “authorized knowers” who give testimony and often have a

prior rapport with the Crown attorneys. Police officers are usually there to help ensure convictions so it is difficult for Crown attorneys when police become the defendants; it is a conflict of interest. If the police can not be held to a higher standard, then we can, at least, demand that they be held to the same standards as us. We must drive home the point that it is a matter of public safety.

Given your experiences within the police force and your knowledge of the inherently problematic role police play in society, what alternative structures of justice and accountability do you envisage to deal with violence and injustice within our communities?

Will: Throughout Canada and Quebec, statistics suggest that crime is on the decline, including murder and other violent crimes. Yet, the number of police officers continues to rise. This strange phenomena is a good starting point for challenging people’s perceived sense of insecurity (exaggerated by mainstream media) and exposing the police institution’s location in a system of state violence.

The most important thing is for people to become self-reliant and take responsibility. Education is important. Many youth don’t know their rights and, until our education system teaches them, we need to teach them. We must advocate against “pro-active” police work and only call police when they’re truly needed; I generally prefer that those doing interventions be from the affected community and have an immediate stake, rather than have them come from outside the community. People can form “intervention groups” within their communities that respond to different situations for which the police would normally be called. These groups will know the community and can propose solutions that reflect the realities and suit the model of that community.

Gaby: We can’t discuss alternatives to the police in a vacuum. Through years of reliance on the police and state, we have lost the ability to govern ourselves. Along with the community policing initiative in the 1980s came the breakdown of the community. Neighbourhood Watch instructed us to watch our neighbours instead of working with them. Community policing contributed to further “dividing and conquering” the community. We need to rebuild social ties in our communities so that we can begin to govern ourselves. We know that the policing structure has deeply-imbedded systemic problems; it will never work because it is built on a faulty foundation. At the very least, we should demand a return to reactive styles of policing whereby police, like fire-fighters, only respond when called, as opposed to proactively looking for crime on the street. When they look for crime, profiling occurs and certain communities are targeted without recourse. We also need to counter fabricated mass media reports of impending crime. This propaganda supports a booming crime and legal industry – lawyers, judges, police, prison guards, weapons, Tasers, crime prevention equipment – when, in reality, crime has steadily been decreasing over the past five years,4 even though our prison population is increasing.5 We should initiate campaigns that tackle our internalized reliance on the police. Only calling the police for incidents of a violent nature is a useful start, but the ultimate solution involves taking back our communities.

Marcel: In our communities, we have to do two main things. First, we have to respond systematically to every police intervention when there is unnecessary repression (with an understanding that it is difficult to directly respond when the intervention involves violence: hostage-taking, gunshots fired, etc.). We have to attack the morale of the police. We must devise means to monitor the police: be witness to police interventions, take pictures, take notes, ask questions, and spread the word that there are cop-watch programs in our neighbourhoods. Complaints should be filed with the ethics commission or other bodies, and these complaints should be widely publicized. Popular education sessions, initially within our movements, and then more broadly, should be instituted.

Second, we must analyze society’s dependence on police as a barrier to constructing a convivial society. We must build infrastructure (street committees, alley committees, neighbours’ committees, residents’ committees) that favor mutual aid and can deal with neighbourhood problems (unnecessary noises, disagreements) without resorting to the police. An example of this is the Café La Petite Gaule, in Pointe-St-Charles, which I was involved with. During its two-and-a-half years of operation, we collectively developed our own ways of dealing with internal problems through dialogue, and only called the police as a last resort. As it turned out, we never called the police; they intervened on their own in a situation two weeks prior to the Café closing down, resulting in one injury and one arrest. These kinds of initiatives demonstrate our capacity to maintain a desired order within the community, to build social and collective links, to make our neighbourhood more secure, and, importantly, to challenge inappropriate police interventions. Ultimately, this can shift the power balance in favor of the people. H

Notes

1. Readers are encouraged to visit the Forum’s website at http://www.forumcontrelaviolencepoliciere.net. Video and audio of this opening roundtable, as well as other sessions from the Forum, will be available online in the near future.

2. On Oct. 7, 1969, Montreal police walked off the job for 17 hours, until they respected a back-to-work law rushed through the Quebec legislature, ultimately returning to their posts after midnight on October 8 (“1969 police strike left city in chaos,” Kevin Dougherty, The Montreal Gazette: Oct 7, 1999, p. A1). The period of the late 1960s corresponds to a significant expansion of state institutions. This meant several hundred police officers were hired each year, most of them coming from working class backgrounds. In 1969, more than half the police force had less than five years of experience on the force, and was strongly influenced by Quebec nationalist and social struggles. During the negotiations around the improvement of working conditions in the force, the Brotherhood resembled a union organization in a labour struggle (i.e. workers vs. bosses), which created a large rift between the police administration and the street level police officers.

3. Lapointe has alleged that he intervened because he saw a group of (racialized) youth playing a game of dice, which is considered a municipal infraction. Tickets for this obscure infraction have been issued only twice in the last fifteen years on the island of Montreal (“La peur de l’agent Lapointe”, Yves Boisvert, La Presse: Feb 15, 2010).

4. “Police Reported Crime Statistics in Canada, 2008”, Marnie Wallace, Statistics Canada, July 2009, Vol.29, no.3: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2009003/article/10902-eng.htm

5. “Incarceration rate rises in Canada”, CBC news, December 9, 2008: http://www.cbc.ca/canada/story/2008/12/09/prison-stats.html