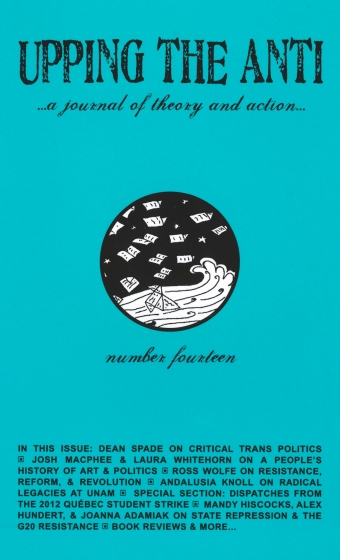

Occupying Then and Now

An Interview with Josh MacPhee and Laura Whitehorn

Occupying Then and Now

An Interview with Josh MacPhee and Laura Whitehorn

Josh MacPhee started making posters for punk bands when he was in high school. Twenty years later, he’s part of Justseeds, a not-for-profit, artist-owned and operated cooperative with members in a dozen cities across the US, Mexico, and Canada. He edited Celebrate People’s History: The Poster Book of Resistance and Revolution (The Feminist Press, 2010), a collection of over 100 posters by some 80 artists and non-artists, commemorating historic events, individuals, and acts of resistance. With his partner, video artist Dara Greenwald, Josh collaborated on a variety of projects, including “Signs of Change,” an exhibit featuring art from the archives of social movements, followed by Signs of Change, a book about the show (AK Press, 2010).

Laura Whitehorn, a sometime artist and full-time radical since the late 1960s, has played a small part in the history Josh celebrates. In 1985, she was arrested with five other activists and spent 14 years in prison on charges of bombing the US Capitol Building and other government sites in protest of the invasion of Grenada and other US aggressions. A few years after her release, Laura met Josh and they struck up a lively political friendship. Laura contributed a poster to Celebrate People’s History that honours Assata Shakur.

Motivated by Celebrate People’s History, Josh and Laura engaged in the following dialogue with Susie Day while Dara was ill with a virulent cancer and unable to take part. Dara died on January 9, 2012. Dara’s work and thought, so much a part of her life with Josh, are present here. We dedicate this piece – exploring unanswerable questions on art and politics – to her.

Let’s start with how you first began making activist art.

Josh: Celebrate People’s History started 14 years ago when my roommate, a Chicago public school teacher, lamented the lack of educational materials that teach progressive, grassroots, social justice history. In the US, we learn a history from above, not the history of masses of people. I was coming at it as more of a street artist, feeling like there wasn’t a lot on the street that was intellectually provocative. The first poster we did was a design based on a linoleum print I made in celebration of Malcolm X’s birthday. We used this quote: “Armed with the knowledge of our past we can charter a course for our future.” In a way, that’s become the motto of the project.

Laura: Before I went to prison, in the 1970s, I was part of the Madame Binh Graphics Collective.1 We were rooted in certain politics; our goals were socialist revolution and supporting national liberation struggles. We tried to get a very clear message across about these struggles.

But at the time I didn’t really see myself as an artist. That changed when I was in prison, where I drew more than ever before. When I made art by myself, it was a way of saying: “I’m still a human being, even though I’m in prison.” But I still find there’s more power in creating something with a group because of the change that goes on.

Describe the Madame Binh Graphics Collective (MBGC). How did it promote that change?

Laura: The MBGC was approximately four people, with additional people helping us screenprint at night. Two of the four had gone to art school and the others were just artistically inclined leftists. Posters were our main form, besides leaflets and t-shirts. We limited the text on most posters to three words.

I think some of our most effective posters were the least artistic. I’m proudest of ones like the little offset poster we made with press type that says, “Assata Shakur Is Welcome Here.”2 We made it with members of the Republic of New Afrika. It was right after Assata Shakur had been liberated from prison in New Jersey, and there was this huge search for her that turned into an attack on Black communities, particularly in Harlem, by the cops. They went into one apartment building in the middle of the night, lined people up in the hallway, and examined the women to see if they had some scar that Assata was supposed to have. They were terrorizing people.

We printed a few thousand posters and distributed them to Harlem stores and around Columbia University and other parts of New York and New Jersey. That poster challenged people to form some kind of security for this woman, who was actually widely loved. It tried to intervene in something that was already going on.

Josh: From talking to you and reading Revolution as an Eternal Dream,3 Madame Binh’s relationship to the movement seemed like a graphic designer’s to a client. You get an assignment, and then you fulfill their desires…

Laura: I don’t agree with you. We were working for an ideal, that’s true. Well, some posters were like that, but the Assata poster was not. It was something created with some of our Black comrades to say, “Let’s express something that this community embraces.” In some of the weaker Madame Binh posters, you can tell it’s more art-by-committee – it’s this image of struggle.

Josh: “There’s got to be red, green, and black…”

Laura: “And we can’t leave women out, so there’s got to be a woman…” That was not as successful as projects when everyone would get excited about an idea that one person had, and then we’d build on it.

Working in a collective, as opposed to working as individual artists, should involve the process of people changing, artists changing. Part of the problem for me in the MBGC was that we didn’t have enough respect for our individual selves; we saw everything in terms of oppression. Who cared whether we became “different people” as artists and human beings? We had to produce a better product to advance the Revolution.

But unlike Justseeds and Celebrate People’s History, it was possible for the MBGC to make a point and raise issues because we were working in a period of tremendous upheaval and resistance. We had already been through the Civil Rights movement, then the Black Power movement and the Vietnam War; when we set out to make art, we were handed the world situation. All we had to do was comment on it and say, “Support this.” The point of Justseeds as a collective and Celebrate People’s History as a collective work is more about creating ideas than creating the struggle. You’re not saying, “Here are the ideas you should support,” but “Let’s start changing so we can take it to the streets.”

Celebrate People’s History was part of building the Occupy movement. When you put out those posters for Occupy Wall Street, they were part of advancing a movement. You were expressing a larger demand that Wall Street should shut up. You know, the Bull with the belt around its mouth?4

Josh: That poster was directly inspired by the popular OWS tool of writing on the backs of pizza boxes. The writing and muzzle were hand-drawn, like the signs; it’s like graffiti on the bull. The cops had put barriers around the actual bull statue, so I was just grafitti-ing on its representation. The hand-drawn part was trying to capture that unique individual hand, not mass-produce a slogan.

How is each of you involved in the Occupy movement?

Josh: From the beginning, my involvement was limited because my primary role in life now is that of caregiver. But I immediately began making graphic work and putting it online to be downloaded.

For me, the graphic work was about channelling what I felt people were saying in a broad sense, and then attempting to put my own political spin on it. I had lots of conversations with people about slogans that pushed the boundaries of issues being discussed at OWS. That led to my getting involved in the Design Working Group.5 I designed a couple of early instructional flyers that got handed out at the park, like: “This is how you get to the info table.” Then I agitated for doing a poster edition of the Occupied Wall Street Journal.6 The idea was to collect images from people involved in the moment around the world and put thousands of copies into the hands of people in the streets.

My desire has never been to replace or supersede the cardboard signs at the park. I love those signs and I’m really sad they got supplanted. You can’t undervalue the role those strange backs of pizza boxes played, because there are so few venues in our lives where we’re encouraged to express ourselves in any way that’s meaningful.

Laura: The main thing I’ve been doing is participating in collective teach-ins on prisons. We immediately hooked up with the People-of-Color Caucus, which wanted to work on that. I’m learning all this process stuff I didn’t know. I’ve been down there every week. I love being there, even though sometimes it’s cold, it’s wet, and the police are intimidating.

I remember teach-ins, especially in college around the Cuban missile crisis and the war in Vietnam, as serious educational speeches and debates. But this is more about using the people’s mic. One person will say, “The prison industrial complex is…” And different people shout out things like, “More Black men in prison than at the height of slavery”; “Women giving birth in shackles”; “Scores of political prisoners.” Then they get repeated. It’s a democratic process.

I marched with some students today and I didn’t mind that they were demanding lower tuition for themselves. It never occurred to me, as it would have in the past, “Oh, that’s just for them. Why don’t they demand something more collective?” Something about the Occupy movement transforms individual demands into collective ones.

How would you two compare the artwork that has sprung up around the Occupy movement with the art that emerged from past political groups?

Josh: The goal of a modern artist, alone in their studio, cutting their ear off or whatever, is self-expression in and of itself, and that has value. But my goal is not to impose my self-expression on the world; it’s to work with larger groups of people to see what collective expression looks like. In the People’s History model, we take a series of individual voices, place them all together, and see what all of the interconnections and dissonances produce.

But what I think is harder, so you see it less often, is the suppression of the individual voice in order to craft a collective voice that’s unique and connected to people on the move. What this collective process produces can be very different from art that is more traditional. There’s something fundamentally different about creating culture outside a mass movement versus being part of a large mobilization. I mean, the People’s History posters are very much informed by the anti-globalization movement. But when there isn’t a movement, you functionally are an artist trying to make art about politics.

Laura: About your political ideas.

Josh: Yes, and when there’s a movement, there’s another option: to dissolve your individual artistic identity into the mobilization and create a cultural product that emerges out of a broader collective desire and articulation.

The most striking thing about Zuccotti Park during those first weeks was that a good quarter of the park was covered by cardboard signs, all done by different individuals. Taken one by one, a lot of them were really nutty – they didn’t make sense alone. You could only begin to understand them in their entirety.

Laura: Though I saw one that was brilliant, that everyone’s quoted, which was: “I’ll believe corporations are individuals when the state of Texas executes one.”

Josh: Sure, there were really cogent, sound-bitable individual signs. But part of what I think made the Occupy experience a movement – at least in New York – was that it provided a place for hundreds, if not thousands, of people to articulate their individual ideas around what was happening to them on these pieces of blank cardboard. Such an extremely heterogeneous articulation had a force that none of the individual signs possibly could – even the best of them. You could not encapsulate their entirety into a handful of words or a handful of pictures. You needed to take literally dozens and dozens of pictures to get a sense of what was going on. It’s a political laboratory like I’ve never seen in my lifetime.

At what point does art become propagandistic?

Josh: There’s a concept of art as somehow autonomous from social contexts. That may be a nice dream; I don’t think it’s possible. For the most part, contemporary art is marshalled to generate money. It’s an industry like any other. If art is going to be marshalled by default for capital, then why not try to marshal some of it in opposition to capital?

Within contemporary art, I would say there’s a bias against politically engaged work. One can be political, as long as the politics are opaque and it’s difficult to understand the artist’s intentions. I’ve gone to a number of art events recently where people have apologized for producing political or social art projects, because they supposedly don’t have the aesthetic staying power of other artwork. But I think the work looks like crap in 99 percent of the Chelsea gallery shows I walk into. Bad art is surely not the sole purview of the political! There’s plenty of nonpolitical work that is absolutely not sublime in any way. At the same time, there’s plenty of political work that is also effective as “art.”

Laura: Some years ago, I went to the Drawing Center in Manhattan and saw a show of drawings by Vietnamese people caught up in the war.7 They were encouraged to draw what was happening.

Josh: I have a book of some of those, Vietnam Behind the Lines: Images from the War 1965-1975.8 In Vietnam, people produced posters on the front lines, where they mixed dirt into the ink to make it last longer and hand painted posters over and over again. When I was in Germany, I found a book of Polish anti-Nazi posters from World War II – they’re rudimentary, stenciled posters made on the front. Very similar. There’s an efficiency that’s very powerful when you see these drawings now; the production is not separate from the message.

Laura: People have sometimes done work like that in the struggle to contain AIDS. But having been in Vietnam right after the war, I saw the country when it was still destroyed. In order to keep morale up and communicate with each other, people created art that was really effective and beautiful.

What did you do in Vietnam, Laura?

Laura: I was part of a four-woman delegation, invited by the Women’s Union of Vietnam in 1975. We went in July, two months after the US was kicked out. We were in the North and we saw the beginnings of an attempt to continue the socialist structures and rebuild after the war. We brought posters we had made with us and gave them to the groups we met with.

People were really touched – we got a huge reaction to these schmatta-looking posters we’d silkscreened, one colour on a piece of paper that probably disintegrated three minutes later. I came back with a much more developed sense of the importance of those political posters and art. To them, it meant there was an image of what they were going through, of their struggle, of their strength, in the heart of their enemy’s territory. And that, to them, was an amazing thing.

Josh: What caught me about the Vietnamese posters in the book was that if you look closely, just about every image has some US plane or helicopter in the background with flames coming out of it. It’s almost like Where’s Waldo? – where’s the F-15 being shot down?

Would you call that propaganda?

Josh: I would. This might be where we disagree. I mean, I didn’t live through that period of struggle, so I have no love for the Stalinist North Vietnamese government – there was a whole counterrevolution happening within the Vietnamese Revolution.

To me, propaganda is instrumentalized culture – and I think that under our current conditions, all culture is instrumentalized. So to me it’s moot. The popular perception of propaganda is Nazi posters or “Buy US War Bonds.” But “I’m Lovin’ It” is McDonalds propaganda.

Laura: Oh yes. But do you consider your work propaganda?

Josh: If people call it that, fine. The assumption that propaganda is bad creates an invisible shield around the fact that the realm where visual communication and ideological projection meet dominates our cultural landscape. Everything we see is propagandistic, yet it’s perceived as benign. It’s “just advertising.”

Laura: What I saw in Vietnam were almost mythic images. The art lionized heroism and sacrifice, and it was beautiful. It was moving. You’re right, Josh, there were always B-52’s that were being shot down. The images in Vietnam were not, “Poor us. Look at our children running down the street burning with napalm.” They were of tiny Vietnamese women dragging these huge planes, taking them apart, and making them into different things. They were beautiful images of women working together, romanticized, similar to Chinese peasant art in phases of the Revolution there. And I felt the purpose they served was to say, “You know what? It’s worth it. We’re fighting for something beautiful and strong.”

The Madame Binh Collective reproduced images of Vietnamese heroines, of the anti-feudalist struggle. But at the time, most of the images made in this country by artists in the anti-war movement were of victimization – which were also true – like the My Lai Massacre.

Isn’t it objectifying to produce images of either victory or victimization?

Laura: That’s one of the roles of political art. You want to expose some of the real brutality. There’s a poster Emory Douglas9 made for the San Francisco 8.10 We heard for months: Emory Douglas is making a poster! Some of my friends from the Defense Committee were there when the poster was finally presented. It’s of a Black, hooded body being tortured, with cattle prods put to the genitals.11 This is exactly what happened to some of the Panthers in New Orleans; in fact, that’s what produced the informant in this case, who was destroyed by weeks of torture.

My friend on the Committee said that when the poster was revealed, all the white people went, “Oh no! I don’t want to look at that,” and all the Black people, a lot of whom were former Panthers, said, “That’s fabulous!” These were utterly spontaneous reactions.

Josh: Dara and I developed a working theory, doing research for Signs of Change,12 that the cultural production of movements does a series of things. One of them is to communicate internally. So the billboards in Vietnam were for communicating with the Vietnamese; they don’t necessarily have the same meaning outside. Another purpose is to communicate with the outside world. There are different, discrete, sometimes overlapping intentions and meanings. I think there’s a tendency to collapse them all or to expect that any one cultural work will serve all purposes.

Laura: Right. And some of the drawings in the Vietnamese show were done by fighters – they’re almost what we might call occupational art therapy. When these poorly armed groups of guerrillas were preparing to be bombed or maybe die the next day, they would do these pen-and-ink drawings of each other the night before. I’m not sure some of that art was ever meant to be displayed.

Josh: It speaks also to the Emory Douglas question. In some ways, the image trumped the argument about whether or not it was the best one to broadcast the SF8 struggle to the outside world. It was equally if not more important that their experience was validated internally.

Who do you see as an audience for your work?

Josh: A lot of my peers and I came to politics through punk rock music and through the idea that we can create our own culture. We had our own bands, we made our own magazines, and we booked our own concerts. We created a world for ourselves that was very different from the world we had to exist in during high school. You’d go to school and drudge through eight hours, then you’d go to this other world that you’d created. One of my friend’s parents had a copy shop, and we would get out the pasting machine, run the copiers, and make publications. We’d have artwork, collages, poetry, and record reviews in them; we were making fanzines.

I came to politics through that culture, and I still treasure its existence. But I also think it becomes a cocoon that remains under the control of the larger world and contains the same repression and limits that everyone has to live under. At a certain point, I thought, “I don’t know if I want to pretend I’m so different from people who don’t have Mohawks or identify with my subculture.” Because, in fact, I have much more in common with them than I have differences.

The last ten years have been a struggle to figure out how to emerge from the counterculture with lessons learned from that experience. How do I move all that knowledge to a place where it really gets tested but still try to move the centre to my margins, rather than the other way around? How does somebody reach a broader audience and bridge those gaps? It’s really hard. There are amazing things about a subcultural identity, but there’s also a kind of built-in – I don’t know if inferiority complex is the right term – but a sense of limits.

Laura: There’s a contradiction at every point. Capitalism is adept at co-opting any system. We’re caught in this: “Are we too radical? Is our art too confrontational? Too jaggedy?”

Josh: I’m not sure that’s the question right now for me. The question is not, “Am I going to be included?” The question is, “Uh-oh, I’m going to be included – what does that mean?” We’re being co-opted, so how do we negotiate that? How do we ensure our labour retains its critical edge?

Laura: But don’t you think that’s a function of history? When I went to the “Signs of Change” show, I was completely floored because there were so many people seeing those posters we made, people who, in the ’70s when they saw the Madame Binh posters, wouldn’t have given us the time of day. They called us “far-left” – we supported Black militancy. So tragedy plus time is comedy? Politics plus time is “Right-On-I-Was-There!” But when art is trying to change people, it has to confront some values. MOMA is not about to show Palestinian art or anti-Zionist art.

Josh: The Guggenheim gave Emily Jacir a prize and her own solo show.13 We’re in a new moment. There’s a struggle going on within the ruling class. There are the Obama types who are confident in ideological control and believe that civil society functions largely as a siphon: within unions, art museums, etcetera, people’s frustration and discontent can be channeled into productive efforts. But you also have the Tea Party people who clearly don’t feel that way. They’re this throwback to an old style of power.

Laura: But the thing about Celebrate People’s History is that it takes art not only out of the museum, out of the gallery, but out of the artist. When I went to the first launch party of People’s History and heard people talking about making their posters, everyone was so passionate. They were studious and said, “I made this poster because it’s important for people to know about the history of the oppression of women in this colonial situation,” or they’d say, “This is my issue! I want to change this!” It was what I think revolutionary democracy is like – messy and all over the place. When I made my poster, I re-learned the power of artistic creation – imagination, passion, principle, personality. All those things that challenge the stranglehold of capitalism on creativity. Who owns it? Who gets to say it?

What about radical artists taking over the mass media occasionally?

Josh: I have mixed feelings about that. I’ve worked in activist art groups that had some ability to get into the mainstream news. I don’t know if you remember the World Economic Forum in 2002 in New York. We had a group in Chicago that brought these giant, six- or seven-foot heads of Bush, Cheney, Wolfowitz, and Rumsfeld. Cheney had an oil mustache; they all had tattooed teardrops coming out of their eyes, showing that they publicly recognized themselves as murderers, and Bush’s lips were sewn shut. Those images were in Newsweek and on the covers of newspapers around the world.

Three-quarters of us said, “That was a success. We need to do that again.” But I actually felt the opposite. When our goal became getting into the mass media, it destroyed the group in a lot of ways. At the same time, there’s increasingly less mass media and more overlapping micro-media, like Facebook and people getting news online. Hollywood movies are still mass, but decreasing numbers of people watch mainstream news on TV, and increasing numbers get their news from a hodge-podge of other sources. Maybe they watch The Daily Show one night, and next day they read the New York Times, and the next day they look at the Guardian UK on their phone.

But people may be starting to understand that there’s a law of diminishing return with this new technology. When the printing press was developed and dissident Protestants during the Reformation started passing out political tracts, they didn’t stop preaching, right? But now, if there’s email, people feel they don’t need to make flyers. Then we get Facebook and we don’t have to send email anymore. But look at what’s successful in the larger world: Starbucks, McDonalds, big Hollywood movies. They put billboards up for a reason – because they still work. They have print ads in magazines – they don’t abandon older strategies, they add newer strategies to their existing arsenal.

Laura: Older societies used storytelling, like African griots.14 But in terms of competition in a capitalist world, we’re at a disadvantage. When you send an email, you don’t change because you don’t actually talk to people.

Josh: That’s why, if a group wants to make propaganda, I advocate that they actually show it to people. With the internet, people can say, “I made a poster and it’s going around the world.” Just because it gets picked up by a couple of other places on the Web doesn’t mean it’s effective at communicating what you think it’s communicating.

Laura: I’m thinking about all the times I’ve seen people wearing Che images and wondered, “Do you really know who Che was?” You know, that cynical thing about the marketing of Che’s image?

There’s a connection between what Che stood for, which has been transformed since his death into meaning everything great about human creativity and love and struggle. Despite the marketing, that can’t be wiped out.

Josh: For lack of a better phrase, I think there’s a double-edged sword here. Within the context of the OWS upheaval, Che t-shirts embody broad conceptions of revolution and human spirit and such. But I think the flipside is that they simultaneously, because of commodification, fail us on another level. We’re no longer able to see Che as a real person and look at his successes and failures – or those of the larger Cuban struggle – in any critical way that lets us learn from those experiences, because Che isn’t tethered to any specific moment or political context. While I value the Cuban Revolution in many ways, we definitely disagree about Che’s legacy, so to me this transcendence from historical specificity means that his authoritarianism, his brutality, his complete and utter failure agriculturally, his dismantling of the unions – we can go down the list – he’s now liberated from those things as well.

Laura: So how would you create art about a martyr? About someone who was killed?

Josh: That’s difficult, and I haven’t successfully done it. I think there’s a tendency within the more vulgar, programmatic Marxism that says that things must happen historically in a certain way. But if that were true, a lot of things in the People’s History posters couldn’t coexist in the same time-stream because they don’t necessarily agree with each other. Other than in the broadest sense, for example, Sacco and Vanzetti aren’t in the same lineage as the Brown Berets, who aren’t in the same lineage as the Plowshares Movement. These are different paths that intersect at different points. The fact that all these things are messy and complicated leads to outcomes no one would have guessed. To me, that’s the opposite of the image of Che.

Laura: I don’t know. I think part of what people revere about Che is his spirit of self-transformation, from a member of the bourgeoisie to a revolutionary. Che’s whatever people want him to be when they wear his t-shirt.

Josh: And that, to me, is the problem. At the point where these people become symbols, they lose connection to their histories. The posters in Celebrate People’s History have dates and information that connects them to specific historical moments. This can make them “didactic” and “educational,” which are traits often seen as bad. But on another level, we’re trying to salvage this history from being a buffet for designers to get new ideas for t-shirts.

Laura: It’s very funny that you’re so much more cynical than I am, and I’m this old activist.

Josh: Initially, in the Design Working Group at OWS, there was a big debate about branding. A whole crew of people wanted to brand the movement because, to them, that’s what success is. I argued vehemently against it. My arguments didn’t stop the branding so much as the group’s inability to corral all the disparate people into a singular visual narrative. So the success of the movement is that it can’t be branded in a clear, traditional marketing sense.

One thing my OWS work has done is make me more confident about creating things that speak to our individual experiences with capitalism, which isn’t just about how Wall Street is extracting X dollars from Y people, but how I and most of the people I know spend increasing amounts of “personal” time on electronic devices. We’re sitting on the toilet taking a shit, but we’re also sending emails to people. Functionally, we’re always at work.

Laura: That is totally going to change how I feel the next time I get an email from you.

Laura, you’re an activist, and Josh, if you’re not an artist, then you’re a cultural worker. You share the same basic politics – but how did you each choose your path?

Laura: The reason I’m a revolutionary – why I made that choice in the ’60s – is because I love people. And capitalism, colonialism, and racism imprison and divide people; they make us less than we could be.

Josh: When I was younger, I did a lot of political activism and I wasn’t that good at it. I’m better at what I do now, so it makes sense to put my energy where there’s greater effect.

But I’m ambivalent about revolution. I feel increasingly ambivalent in general. I think we can be better, there’s absolutely no question about that. And I think there’s very little that human beings can’t accomplish if we actually learn to work together, rather than compete for individual gain. But I’m pretty open as to how we get there.

I look at history and I see that the things that have been relatively successful are often a strange mish-mash of all kinds of different perspectives and people and initiatives. The certainty that one line of political thought is the way just doesn’t seem historically tenable to me. It’s not how things happen. Things happen because thousands of people are doing thousands of things, and there’s a sort of explosive chaos that produces different opportunities. You never know what those opportunities are going to be before you enact those politics.

Things like posters, t-shirts, street performances, film or audio can seem marginal – and then something like Egypt or Wisconsin happens. This is the centre of the universe right now, people producing culture to liberate themselves.

Laura, is it more important to you to do nuts-and-bolts activism than art?

Laura: My vision of socialism – which I still believe in firmly, whether it’s worked so far in the world or not – is that it frees people to be collectively what they’re impassioned about individually. What I mean by revolution is not different from what Josh is saying about mass chaos, thousands of people moving something. I just think there have to be some guiding goals, which change as you get there.

Josh, you’re one of the best organizers I know, because you trust people, even when you disagree with them. And I think that’s why Celebrate People’s History is so successful. It’s a revolutionary act in itself. H

Notes

1. Madame Binh, now the Vietnamese Minister of Education, was a revolutionary leader during the war on Vietnam.

2. Assata Shakur, African-American revolutionary, was a leader in the Black Panther Party and the “Soul of the Black Liberation Army.” Imprisoned after a 1973 confrontation with police on the New Jersey Turnpike (in which she was shot by police), she escaped in 1979. In 1984 she was granted political asylum in Cuba. She continues to be targeted by US law enforcement.

3. Mary Patten, Revolution as an Eternal Dream: The Exemplary Failure of the Madame Binh Graphics Collective (Chicago: Half Letter Press, 2011).

4. “Money Talks … Too Much. Occupy,” poster by Josh MacPhee, 2011. See, http://justseeds.org/josh_macphee/04moneytalks.html.

5. Occupy Wall Street Design Working Group, created in New York City, fall 2011, is still active: https://facebook.com/OWSdesign?sk=wall.

6. The Occupy Wall Street Journal, poster edition, http://occuprint.org/Info/OWSJ and http://flickr.com/photos/akinloch/6338651280/.

7. “Persistent Vestiges: Drawing from the American-Vietnam War.” The Drawing Center: New York, NY, November, 5 - December 21, 2005. http://drawingcenter.org/exh_past.cfm?exh=82.

8. Jessica Harrison-Hall, ed., Vietnam Behind the Lines: Images from the War 1965-1975 (London: British Museum Press, 2002).

9. Emory Douglas was the Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party; his artwork was featured in the Party’s newspaper. He remains a graphic artist and lives in San Francisco.

10. In January 2007, eight former Black Panthers were charged in the 1971 shooting death of a police officer in San Francisco. The case, based largely on evidence from the tortured confession of some of the suspects, never came to trial. Two defendants pled guilty to voluntary manslaughter; charges against the others were dropped.

11. “Free the SF8,” poster by Emory Douglas, 2008. See, http://freethesf8.org/Emory_Douglas_poster.html.

12. “Signs of Change,” an archive assembled by Dara Greenwald and Josh MacPhee, includes over 350 posters, prints, photographs, films, and videos exploring global struggles for liberation and human rights. It was exhibited in 2009 at Exit Art, a cultural center in New York City. Much of the show can now be seen in Signs of Change: Social Movement Cultures, 1960s to Now, Greenwald and MacPhee, eds. (Oakland: AK Press, 2010).

13. Emily Jacir is a Palestinian conceptual and performance artist whose work depicts the plight of the Palestinian people. In 2008 she won the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation’s Hugo Boss Prize. http://nytimes.com/2009/02/13/arts/design/13jaci.html.

14. Griots are part of the West African oral tradition, conveying history through storytelling, praise singing, poetry, and music.