The Politics of Solidarity

Six Nations, Leadership, and the Settler Left

This article will address some issues which have arisen in the context of non-native activists doing solidarity work with the Haudenosaunee (Six Nations) people of the Grand River Territory who recently reclaimed land near Caledonia, Ontario.1 I will begin by discussing the problems with how many non-native activists have used the concept of “taking leadership” to guide their activism around this struggle, and I then will look at the spaces and places where I think non-native activists should focus their efforts in support of indigenous sovereignty. In order to do so, I will draw on the work of black power activists Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton as their work provides a relevant model for non-native activists looking to build solidarity with Six Nations. I will conclude by addressing the importance of the work being done by trade union activists supporting the people of Six Nations.2

At the outset, I want to suggest that the theoretical claims that I am advancing are contingent on the historical specificity of the Six Nations community of the Grand River Territory. And so, while there are aspects of my argument that may be relevant to other indigenous struggles and aspects of solidarity work more generally, the Six Nations community is unique in many ways. With over 20 000 registered residents, the Six Nations people of the Grand River Territory comprise the single largest indigenous community in Canada and, in certain regards, they have managed to withstand the pressures of Canadian colonialism better than many other indigenous nations in the south of Canada. The alliances the Iroquois Confederacy made as equals with European nations and the cosmology which frames their constitution – the Great Law of Peace – provide them with a clear political framework to guide contemporary relations with settler society. Finally, their claim to the Haldimand tract – almost a million acres of prime agricultural land in southern Ontario on the outskirts of one of Canada’s greatest industrial and commercial conurbations – strikes at the heart of Canadian capitalism and the state’s appropriation of indigenous lands. For these reasons, and in light of the fact that indigenous resistance and the solidarity movements that support it are constantly evolving, it is important not to mechanically extend the claims I advance here to other contexts where they may not be applicable.

The Problems With “Taking Leadership”

The question of how to relate to the struggle at Six Nations has been of great concern to many non-native solidarity activists. Discussions about how to get involved have largely been framed around the notion of “taking leadership” from the people of Six Nations.3 This approach stems from an anti-oppression perspective that grants epistemic privilege to those most oppressed by Canadian colonialism, those seen as best able to identify the kind of support they need. From this perspective, the primary role of non-natives is to act as allies standing in solidarity with a struggle whose decisive battles will be fought outside their own location in Canadian settler society.

While I would be the first to argue that any non-native activist interested in doing solidarity activism needs to work in close collaboration with indigenous activists and must be responsive to indigenous experiences and political perspectives, the notion of “taking leadership” has not been very helpful in building meaningful support for the people of Six Nations. As I will explain below, this is principally because the people of Six Nations have not operated on the basis of considering themselves to be “giving leadership” to their non-native allies. In practical terms, waiting for “leadership” has often meant that non-native activists have avoided looking at how their own social location implicates them in Canadian colonialism while simultaneously providing them with opportunities to disrupt it. By waiting for indigenous people to provide “leadership,” and by assuming that successful resistance to colonialism can only happen through high-profile barricades or occupations, many crucial opportunities to build non-indigenous support for the struggle at Six Nations have been missed.

Fundamental problems have arisen for solidarity activists who have determined that their activity can only take place with the permission of, and under the leadership of, indigenous people. The biggest difficulty has been finding an appropriate indigenous political group to lead them. For example, the Toronto-based Coalition In Support of Indigenous Sovereignty (CSIS) – through which anti-capitalist groups including the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP), No One Is Illegal, the Arab Students Collective, and the Canadian Union Public Employees (CUPE) Local 3903 International Solidarity Working Group have coordinated their efforts – was deliberately structured to be small, inwardly focused, and closed to new membership so as to better function “under the leadership” of the small Indigenous Caucus of the organization.

Unfortunately, the organization was limited by the fact that its Indigenous Caucus never consisted of more than three active members, none of whom were from Six Nations. Although the coalition engaged in some important activities like fundraising, organizing events, and bringing supporters to the reclamation site, group member Stefanie Gude points out that deliberately limiting the membership to “ensure that the group was not overwhelmingly non-native” contributed to the fact that it “failed to pursue the interest and energy being felt by countless people from all different sectors and populations outside of that structure and outside of OCAP.”4

The situation has been no less complex when solidarity activists have sought to take direction from the Six Nations community itself. Here, the difficulty arises from three particular dynamics. First, the existence of a wide and conflicting range of opinions and perspectives within the Six Nations community as to how their struggle should be advanced; second, the distinct and overlapping decision-making processes that produce many different layers of leadership within Six Nations; and finally and most fundamentally, the principles of the Two Row Wampum which govern the traditional Six Nations relationship with European settler societies and indicate that neither nation should interfere with the internal affairs of the other.

It should not be a surprise that, just as in any community, there are divisions within Six Nations. The community is not monolithic, and it is divided along lines of religion, occupation, and class, as well as by family networks and business interests. There are divisions between an older generation of traditionalists who have little interaction with non-native society and younger activists who use the internet to share their opinions and perspectives. On top of that, there are different and conflicting interpretations of the Great Law, or guiding constitution, of the Six Nations; tensions between the different nations that make up the Confederacy; political differences between warrior society-inspired groupings and some traditional Confederacy leaders; and differences based on people’s positions at the reclamation site and the length of time they have spent there.

When such a complex situation is refracted by the diverse channels through which political power is exercised within the community (including clan mothers and traditional chiefs, the band council, men’s and women’s councils, NGOs, and various levels of formal and informal on-site leadership), it is impossible to maintain that a particular person or grouping speaks on behalf of the people of Six Nations of the Grand River. The Six Nations Confederacy is perhaps the body that comes closest to functioning as a “traditional leadership” for the people, but it is important to keep in mind that Confederacy process and leaders operate in a very different way than “leaders” and government in non-native society do, and that even within the community there is debate about how “traditional” (and thus legitimate) the Confederacy leadership actually is.

The second aspect of this problem arises from the fact that, as Six Nations activist Brian Skye pointed out in a recent interview, outside organizations can and should relate to several different decision making bodies involved in the reclamation. Grassroots non-native organizations should, he argues, relate to the grassroots people present at the reclamation site. Skye suggests that more established “funded organizations,” including NGO’s and trade unions, would more appropriately relate to the negotiation table and its various side tables (including the archaeological, educational, and consultation side tables). For Skye, the highest level of interrelationship between settlers and Six Nations must take place at the national level where the Canadian government should relate to the Six Nations Confederacy on a nation-to-nation basis.5

If grassroots activists accept Skye’s framework of mutual and overlapping levels of Six Nations decision making, then it would seem most appropriate for them to build links with those people at the reclamation site. However, in building these relationships, it is important not to conflate the perspectives or politics of the individuals most active at the site with those of the traditional Confederacy leadership or the community as a whole. The composition of the people at the site is often in a state of flux, and there have been significant areas of disagreement between Six Nations activists and the Confederacy leadership.

In some cases, such as in the decision of Confederacy leaders to bring down the barricades (against the wishes of many site activists, and without following the established consensus-based process), it was relatively easy for non-native activists to get out of the way and allow the internal politics to work themselves out. However, another problem arose several months later when longstanding divisions between different traditionalist elements in the community became apparent. This time, it was not so easy for non-native activists to remain uninvolved. The divisions stemmed from wording in the Haldimand tract document that promises the granted land to “the Mohawks and their followers” – a phrase that has provoked disagreements between the Confederacy and a group of Mohawks within the community over who holds the title to the Haldimand tract and with whom the Canadian government should be negotiating.

Matters came to a head with the case of Trevor Miller, a Mohawk man arrested at another indigenous blockade near Grassy Narrows in August of 2006 for his actions in defense of the Six Nations reclamation site. Miller and his family felt that they had not received adequate community support because of their political differences with the Confederacy. Several months into his imprisonment, they turned to members of the Traditional Mohawk Council of Kanehsatake and to non-native solidarity activists for support. Because non-native activists felt that it was important to demand that the Canadian government cease its criminalization of indigenous activists, the matter quickly became an important area of solidarity work. Groups like the Caledonia based Community Friends organized demonstrations and vigils outside the Hamilton jail where Miller was being held.

At the same time, and because of longstanding political and personal differences they had with Miller’s friends and family, many people at the reclamation site were skeptical of the solidarity campaign. The situation was made all the more difficult by the fact that – in addition to the charges he faced for defending the reclamation site – Miller also faced an earlier set of charges relating to an alleged physical assault of his ex-partner who did not want him to be released from custody.

Although activists from groups like OCAP (Toronto), Community Friends (Caledonia) and the Committee in Solidarity with Six Nations (Montreal) made a distinction between their support of indigenous political prisoners and the actions of these prisoners in matters unrelated to their struggle against the Canadian state, the situation again intensified when a group of Mohawks associated with the Trevor Miller defense campaign launched a $4.5 trillion lawsuit against both the Canadian government and the Six Nations Confederacy. The case was filed by the same lawyer who had represented Miller in court and was backed by many of the Six Nations Mohawks who had been instrumental in building the campaign for Miller’s release, some of whom have radical politics and long-standing ties to indigenous and anti-racist movements in the US and Canada. Key in the debate over both the lawsuit and the question of legal defense for Miller was a critique raised against the Confederacy for having a non-traditional leadership because it followed the “Code of Handsome Lake” which mixes religious principles derived from Christianity with traditional teachings.

Since they needed to choose with which set of radical indigenous activists they would ally themselves, solidarity activists were left in in a quandary. In this kind of a situation, the question of “taking leadership” from the affected community becomes very complex. Because “leadership” in concrete situations always comes from specific individuals and groups operating in particular contexts, any solidarity group claiming to “take leadership” from the community must (whether they admit it or not) first make the political choice as to which element of the community they will take leadership from. This choice is based on what is perceived to constitute appropriate leadership within the community and is made all the more difficult given that non-native activists can only have a limited understanding of the internal debates and politics taking place within the community. Furthermore, the decision of outside activists to “take leadership” from a particular grouping also has ramifications within the community. Since the side with access to outside support and resources is strengthened, the support of non-native groups can often distort the internal dynamics of the community.

There is a third factor that makes the concept of “taking leadership” even less tenable. The Two Row Wampum agreement, which has historically defined the Six Nations relationship with settlers, holds that both the Six Nations community and the settler communities are to “steer their own boats” and not interfere with each other’s internal affairs. Since their first contact with Europeans, the history of Six Nations has been one of continuous struggle against encroachment on their lands and their systems of government. The political response of Six Nations has been to insist on the primacy of the Two Row Wampum and to demand that each nation mind its own internal business.

Given the principles of the Two Row Wampum, it is easy to understand why neither the Six Nations Confederacy leadership nor the Six Nations community more generally has stepped forward to “provide leadership” to the non-indigenous peoples that support them. The theoretical framework guiding their understanding of the inter-relationship between native and non-native communities works against it. Non-native grassroots activists at the reclamation site can clearly interact as individuals with native activists but, according to the Two Row Wampum, it would be inappropriate for the Confederacy – the traditional Six Nations leadership – to tell those activists and their organizations what to do within the Canadian state to push their government to come to a position in support of Six Nations. To do so would be a violation of the Two Row Wampum that would legitimize attempts by the Canadian government or its agents to meddle with the internal affairs of Six Nations.

Learning from Black Liberation

If the principle of “taking leadership” from Six Nations is deeply flawed, then what kind of model can guide the actions of non-native solidarity activists? I believe that one of the best parallels for understanding the situation can be found in the difficult relationship between the black liberation struggle and the radical white left in the US during the 1960s and 1970s. During this period, the black liberation movement became a focal point for many different communities and political struggles. As black liberation moved from “non-violent” civil rights struggles to ghetto uprisings and revolutionary political formations like the Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Army, white activists grappled with how they should relate to a clearly revolutionary struggle happening outside of their own communities.

Significant theoretical elaboration of this dynamic occurred within the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an important civil rights organization that spearheaded voter registration drives in the US South. SNCC leader (and later honorary Black Panther Party Prime Minister) Stokely Carmichael wrote and spoke extensively about the relationship between white radicals and the black liberation struggle. Although written in a different political context, much of what he argued is of great relevance to the question of how non-native activists should relate to the struggle of indigenous people within the Canadian state.

In a book Carmichael co-wrote with Charles Hamilton entitled Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America, they argued that black people must build their own organizations to represent their own interests. According to Carmichael, only once black people have their own “genuine power base” should they enter into coalition with white allies who, in turn, must also have their “own independent base of power.” Once each group had a power base and a political organization, they could come together in coalition to work for specific and identifiable goals.

The people of Six Nations are clearly working to build and strengthen their own organizations and “genuine power bases” on their territory. That this process has been strengthened by the reclamation is clear by the growing level of community mobilization and the fact that the Canadian government has been forced to negotiate with the Six Nations Confederacy – a body that continues to gain support within the community. Unfortunately, a comparable process of radicalization and organization is not taking place in nearby non-native communities where the left remains fractured, tiny, or simply nonexistent.

Carmichael and Hamilton were writing in a context of a significant upsurge of white radicalism. The problem was that, too often, the white left would ride on the coat-tails of black radicalism rather than confront sources of exploitation and oppression coming from within their own communities. As Carmichael and Hamilton noted:

One of the most disturbing things about almost all white supporters has been that they are reluctant to go into their own communities – which is where the racism exists – and work to get rid of it. We are not now speaking of whites who have worked to get black people “accepted” on an individual basis, by the white society. Of these there have been many; their efforts are undoubtedly well intended and individually helpful. But too often these efforts are geared to the same false premises as integration; too often the society in which they seek acceptance of a few black people can afford to make the gesture. We are speaking, rather, of those whites who see the need for basic change and have hooked up with the black liberation movement because it seemed the most promising agent of such change.6

In the context of ongoing anti-native agitation against the Six Nations land reclamation within pre-dominantly white communities such as Caledonia, the failure of the white left7 to intervene has been nothing short of scandalous. Slick media savvy personalities like Gary McHale have organized dozens of rallies and public meetings based on David Duke-type arguments against “two-tiered justice” where they have effectively demanded “equal rights for whites” who are seen as oppressed because the Canadian state has not moved in to stop the “terroristic” natives. Dozens of open neo-Nazis have participated in public events organized by McHale.

Despite this, the white left has not come up with a single meaningful response to the situation. While Toronto leftists tormented themselves with the question of whether or not it would be appropriate to organize in small communities where they have no pre-existing base, neo-Nazis and far right organizers plunged in, building networks and alliances that have successfully brought ever more pressure to bear on both Six Nations and the federal and provincial governments. By failing to organize within the predominantly white communities surrounding Six Nations, the white left has effectively ceded this terrain to racist demagogues and allowed McHale and his cronies to speak unopposed on behalf of the “average hard-working, taxpaying, middle-class Canadian” of the area.

Despite the privilege historically enjoyed by US whites in relation to black people, Carmichael and Hamilton did not simply write them off. Unlike many leftists today, Carmichael and Hamilton did not consider white settlers incapable of leftist activity or unworthy of political organization. Not only did they view poor and working-class whites as potential allies to the black liberation struggle, they argued that even white middle-class communities needed to be organized:

Across the country, smug white communities show a poverty of awareness, a poverty of humanity, indeed, a poverty of ability to act in a civilized manner toward non-Anglo human beings. The white middle-class suburbs need “freedom schools” as badly as the black communities. Anglo conformity is a dead weight on their necks too. All this is an educative role crying to be performed by those whites so inclined.8

While recognizing that white people can make certain important contributions to non-white struggles, Carmichael and Hamilton insisted that white people must not seek to live vicariously through the radical struggle of black people, but rather must take responsibility for their own communities and their role in their own liberation:

It is our position that black organizations should be black-led and essentially black-staffed, with the policy being made by black people. White people can and do play very important supportive roles in these organizations. Where they come with specific skills and techniques, they will be evaluated in those terms. All too frequently, however, many young, middle-class, white Americans, like some sort of Pepsi generation, have wanted to “come alive” through the black community and black groups. They have wanted to be where the action is – and the action has been in those places. They have sought refuge among blacks from a sterile, meaningless, irrelevant life in middle-class America. They have been unable to deal with the stifling, racist, parochial, split-level mentality of their parents, teachers, preachers and friends.

Carmichael and Hamilton’s words are of particular relevance to the white activists that came out to support the reclamation site during the tense period of the standoff when barricades blocked nearby highways and rail lines. For many white activists, this was the revolution, the high point of struggle, and they were living it by washing dishes or doing menial labour around the camp, or just by being there as physical or moral support. Very few of these activists made an attempt to understand why thousands of white people not so different from themselves were protesting against the reclamation site only a couple hundred yards away, or to figure out how this racism could be effectively combated.

While cooking and cleaning did make a contribution to the camp, I believe that it was more effective in assuaging white guilt than it was in shifting the balance of forces arrayed against Six Nations. The focus on cooking and cleaning as the most appropriate expression of non-native solidarity flowed from the premise of “taking leadership” from Six Nations. When faced with dozens of (mostly) white hippie/punk youth with few camp-related skills and no prior contact with people at Six Nations, it is not surprising that Six Nations people directed them to do menial labour around the camp. Because this is what they were told to do, and because many of these white and/or middle-class activists were uncomfortable talking to white working-class Caledonians that they perceived as the enemy, food preparation was fetishized as the primary way for non-natives to contribute to the struggle. The possibilities of leftist non-natives intervening in the anti-native protests was never openly broached as a potential political strategy. Given that it was not safe for indigenous people to intervene in the Caledonia protests or to organize within the Caledonia community, and given that the indigenous activists at the reclamation site had their own community to organize, people from Six Nations stayed within the perimeter they had set up. Most white activists assumed that they should do the same.

Like the rest of settler Canada, and like Six Nations, Caledonia is not monolithic. From the very beginning of the standoff, it was Caledonian business interests that organized resistance to the land reclamation and purported to speak on behalf of the whole community. The Caledonia Citizens Alliance was formed and funded by the Caledonia Chamber of Commerce and represents the bankers, lawyers, and realtors who stood to make vast profits from “developing” Six Nations land. Middle-class and business-oriented political organizations with deep ties to local government also played key roles in attacking Six Nations and providing support for individuals from outside of Caledonia like Gary McHale.

There are certainly deep currents of anti-native racism within the community. Nevertheless, it would be truly shortsighted to label all Caledonians and settlers in the nearby area as racists or as people with interests objectively opposed to Six Nations people. First of all, there are people from Six Nations and various different ethnic groups living in Caledonia. Although they have tried for the most part to keep their heads down during the standoff, they form a potential base of support for anti-racist activity. There are also many white Caledonians who do not support the growing racism in their community and who would be willing to take action in support of Six Nations if they had a framework from within which to work.

Unfortunately, because most of Caledonia’s “civil society” organizations are connected to the business interests that want to develop the Haldimand tract, such organizations must be built from the ground up. In the words of Carmichael and Hamilton: “this job cannot be left to the existing institutions and agencies, because those structures, for the most part, are reflections of institutional racism.”9 The unorganized and atomized people of Caledonia who support Six Nations include people with indigenous friends and family, church goers, high school youth, and people with no personal connection to the issue but who to varying degrees support Six Nations. Anti-native racism no doubt poses serious barriers to building solidarity with Six Nations. Nevertheless, we must recognize that white people in Caledonia are not intrinsically any more racist than white Canadians anywhere else.

Caledonia is located in Ontario’s “golden horseshoe” – an area with one of the largest unionized populations per capita in North America. This concentration of trade unionists has influenced the nature of support for Six Nations. Not only have significant union organizations supported the reclamation by passing motions and sending donations, but the majority of solidarity activists involved in building groups like Community Friends are unionized workers even when they are not actively involved in the trade union movement.

There are many possibilities for organizing in support of Six Nations in Caledonia and other metropolitan communities. Of particular importance are the large racialized communities in nearby cities like Hamilton, Kitchener Waterloo, and Toronto whose members experience many of the same kinds of racism and class oppression faced by the people of Six Nations. Especially because these groups live in such close proximity to one another (Six Nations is a one hour drive from each of these large population centers), it is a lot easier to build links and connections with Six Nations than with indigenous communities located thousands of miles away.

In Carmichael and Hamilton’s analysis, various communities interested in working with each other should operate on the basis of developing political organizations rooted in each community that are able to work together as allies – not on the basis of one organized community providing a one-sided “leadership” to an another atomized and disorganized community:

It is hoped that eventually there will be a coalition of poor blacks and poor whites. This is the only coalition which seems acceptable to us, and we see such a coalition as the major internal instrument of change in the American society. It is purely academic today to talk about bringing poor blacks and poor whites together, but the task of creating a poor white power bloc dedicated to the goals of the free open society – not one based on racism and subordination – must be attempted. The main responsibility for this task falls upon whites. Black and white can work together in the white community where possible; it is not possible, however, to go into a poor [white] southern town and talk about “integration,” or even desegregation [together]. Poor white people are becoming more hostile –not less – toward black people, partly because they see the nation’s attention focused on black poverty and few, if any, people coming to them.10

The situation today is analogous. Racism is growing in towns like Caledonia, and recent polls have suggested that non-native support for indigenous rights is decreasing as conflicts intensify. While some of this backlash clearly arises due to racism and fear that their own standard of living will inevitably decline if indigenous people gain rights, this erroneous position remains unchallenged precisely because there is so little anti-racist, anti-colonial, and anti-capitalist work taking place within non-native communities. Non-native people do not have to suffer in order for the rights of indigenous peoples to be respected, and the left needs to make the argument that the funds needed to pay reparations to native people should come from the coffers of the corporations that have profited from the plunder of native lands and the exploited labour of all workers. A radical approach to actualizing indigenous sovereignty requires both political and economic transformation – the full sovereignty of indigenous nations must be recognized and the capitalist economic system that exploits both non-natives and natives must be overturned.

Organizing Our Own

For non-native radicals, the fundamental question raised by the reclamation relates not only to how we organize as non-natives in solidarity with oppressed people, but also to our vision of a movement that can challenge the oppression facing the working class majority of Canadian settler society. This requires overcoming the dichotomy between two disparate positions that have long afflicted the radical left. One position holds that it is impossible to build a mass based radical movement among the (predominantly white) Canadian working class due to its relatively privileged status, while the other maintains a narrow and economistic focus on specific (white) working-class struggles without making links to the intersecting relations of race, sexuality and gender that concretely define the reality of class oppression.

If we can transcend this dichotomy – that is, if we can accept that non-native North Americans can be mobilized around social and economic issues that are connected to a project of social liberation that we share with indigenous people – then new forms of solidarity and resistance can emerge. In the case of the Six Nations struggle, one urgent task is to organize among southern Ontario union activists who are supportive of the struggle for sovereignty and to build a grassroots organization that can advance indigenous and working class struggles. This strategy is not about abstractly “showing solidarity” with Six Nations. It is about building an independent and radical base in the union movement that can unite a wide range of anti-racist, anti-poverty, and class struggles which affect its members personally.

Looking to organized labour for support for Six Nations is not a fantasy. In fact, some of the best and most sustained support for Six Nations has come from labour activists. One of the most notable examples of this support has come from United Steel Workers Local 1005 at the Hamilton Stelco plant which has not only conducted intensive and ongoing internal educationals on indigenous sovereignty and the Six Nations struggle, but has regularly sent dozens of their members to bolster protest lines at the reclamation site. In addition to providing financial assistance, members of the local have also regularly attended solidarity demonstrations in Hamilton to support Six Nations political prisoners and helped to organize a contingent of people from Six Nations to participate in the Hamilton Labor Day parade. Enthusiastic support and significant financial donations have come from CUPE locals 3903 and 3906, who have also been active in organizing demonstrations and activities in Toronto and Hamilton. Many other unions have sent delegations to the site to learn more about the Six Nations struggle. Rank-and-file trade unionist involvement continues to be central to the Caledonia-based Community Friends group, which benefits from the regular participation of workers belonging to more than a dozen different trade union locals.

So, while there is obviously a disconnect between the press releases and sympathetic motions passed by the labour leadership and the need for committed and long term solidarity at the grassroots level, real connections between indigenous and labour struggles exist and they provide a basis upon which real solidarity can be built. Both Lindsay Hinshelwood (a rank and file factory worker at Ford with CAW 707) and Steve Watson (a CAW leader) have on separate occasions made the following observations about the connections between indigenous and trade union struggles:

- Governments and the corporations they represent seek to exploit workers and regularly seek to roll back or disregard the collective agreements which are intended to safeguard workers’ rights. Like the contracts of unionized workers, indigenous people have treaties which outline their collective rights. Governments and corporations constantly disregard these treaties in their search for power and profits.

- When workers feel like their contract isn’t being respected or needs to be improved and bargaining isn’t working, they set up a picket line, demand that no-one crosses, and are often required to use direct action (in contravention to the law) in order to win their demands. When indigenous people can’t get their rights respected they take similar direct action through organizing blockades or occupations of disputed land which similarly disrupt the economy.

- One of the fundamental axioms of trade unionism is that “an injury to one is an injury to all” and unions have become increasingly concerned with issues that matter to all people – sexism, racism, the environment, queer rights, support for indigenous struggles, and resistance to capitalist globalization. The worldview of indigenous peoples rejects the commodification of land and labour and is similarly concerned with universal questions of human freedom and self expression in the context of harmony with the natural environment.

Other parallels can be drawn. The European settlers who colonized most of North America, were themselves uprooted from the land through capitalist enclosure and the commodification of land and labour – a process later exported to the indigenous peoples of the Americas and the rest of the world. By becoming small farmers and independent commodity producers in the early stages of Canadian development, poor and working class settlers in North America clearly benefited from the theft of indigenous lands. However, over the past 100 years, capitalism has extended and intensified its reach. Non-native people have become increasingly concentrated in large cities (Canada has the most urbanized population per capita in the world) and have been integrated into the capitalist system as workers. Because of the inherently exploitative dynamics of capitalism, workers in North America have faced a decline in living standards since the neo-liberal offensive of the late 1970s.

As William Robinson has argued, the contemporary resurgence of indigenous struggle in the Americas is happening as the few remaining autonomous indigenous communities are being forced into compliance with the demands of capitalist world market. This market seeks to commodify their labour and their land. At the same time, it seeks to drive down living standards and commodify the lives of non-native people as well.11 These pressures are just as evident on the Haldimand tract as they are in Canada’s far north, in the mountains of Chiapas, or in the jungles of the Amazon. Traditional indigenous resistance to enclosure and commodification is increasingly assuming a directly anti-capitalist character. When this resistance takes place in large urban areas where a relatively small proportion of settlers directly occupy the land in question, new opportunities for joint struggles arise. Doing this kind of work will not be easy. Building radical organizations and combating white racism within predominantly white communities, workplaces, and political organization will be particularly hard. But it remains necessary task as a pre-condition to building meaningful solidarity with indigenous struggles.

Work to build and consolidate networks of grassroots union activists must be prioritized. This force can push the trade union bureaucracy both to give more meaningful support to indigenous struggles and to build autonomous rank and file networks to fight for their own interests. Unionized workers represent only one sector of the working class – but it is the sector which today can be most easily moved into political action. There is already a small but real base in the union movement of southern Ontario that can begin this project. The Six Nations struggle offers an important opportunity to build a solidarity movement with the social power and the long-term interest needed to challenge both colonialism and capitalism in Canada. We need to take the initative in building that movement. ?

Notes

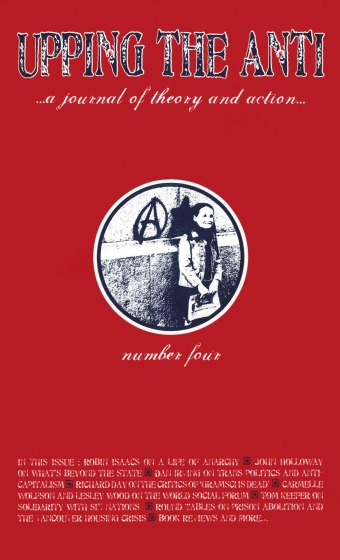

1 For more information and background about the Six Nations struggle, please see the various articles and interviews relating to Six Nations in Upping The Anti #3 as well as the online resources compiled at the A&S Six Nations Caledonia Resource webpage at http://auto_sol.tao.ca/node/view/2012.

2 In terms of situating my own experiences in this struggle as a non-native person, for the past year my work in this area has centered on working with a coalition of rank-and-file trade union activists drawn from the surrounding area, non-native people from Caledonia, and people from Six Nations who have come together in a group called “Community Friends for Peace and Understanding with Six Nations.” The group, which has a core membership of around a dozen people and which has had more than 150 people attend its twice-monthly organizing meetings over the past year, has worked in a number of ways to organize solidarity with Six Nations. Although most meetings have a significant presence of indigenous people (one third to half of the room is usually from Six Nations) the work of the group has primarily focused on strategies to identify and build non-native sources of support for Six Nations within surrounding settler communities. This has taken on a variety of forms including going door to door in Caledonia to meet and talk with residents, trying to organize funding and support from trade unions, and has also involved the holding of a number of educational meetings directed at the nearby settler population as well as attempting to raise awareness about the situation of Six Nations political prisoners.

3 See especially “From Anti-Poverty to Indigenous Sovereignty: a Roundtable with OCAP Organizers,” with Stefanie Gude, AJ Withers, and Josh Zucker in Upping The Anti #3.

4 Stefanie Gude, “From Anti-Poverty to Indigenous Sovereignty,” Upping the Anti #3, p. 162.

5 See “The Political Significance of the Reclamation: an Interview with Brian Skye,” Upping the Anti #3, pp. 135-142.

6 Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton, Black Power: the Politics of Liberation in America, pp. 81-82.

7 I should note that in using terms such as the “white left” and the broader term “non-native activists” I am making a distinction between activists groups which are primarily made up of white activists such as OCAP or various trade union or socialist formations, and groups primarily made up of people of colour such as No One Is Illegal, the Black Action Defence Committee, and the Arab Students Collective. I am arguing that predominantly white organizations have a special responsibility and ability to organize in predominantly white communities such as Caledonia and that people of colour groups often have a different set of priorities and responsibilities in terms of how they relate to indigenous struggles.

8 Carmichael and Hamilton, Black Power, p. 82.

9 Carmichael and Hamilton, Black Power p. 83.

10 Carmichael and Hamilton, Black Power p. 83.

11 See the interview with William Robinson “Latin America, State Power, and the Challenge to Global Capital” Upping the Anti #3, pp. 59-75.