Resistance, Reform, Revolution

Revisiting the Terms of Debate

Resistance, Reform, Revolution

Revisiting the Terms of Debate

Ross Wolfe

Almost five years have passed since Platypus hosted its first panel on “The 3 Rs: Reform, Revolution, and Resistance.” At the time, many of us were trying to come to terms with the profound sense of disorientation we felt during our involvement in the anti-war movement, which was rapidly disintegrating. In order to determine whether an emancipatory politics was still even possible, we explored these three categories – reform, resistance, and revolution – in relation to one another and to the greater project of human freedom. How can these three political modes be deployed to advance social and individual freedom? How might they reinforce each other? Today, with recent upsurges in global activism, we stand on the precipice of a rebirth of such a politics. In this context these questions acquire a renewed sense of urgency; now more than ever, they demand our attention if we’re to forge a way forward without repeating the mistakes of the past.

Reform, revolution, and resistance: each of these concepts exercises a certain hold over the popular imagination of the Left. While they need not be conceived as mutually exclusive, the three have often sat in uneasy tension with one another over the course of the last century. The Polish Marxist Rosa Luxemburg famously counterposed the first two in her pamphlet, “Reform or Revolution?” written over a hundred years ago. In her view, this was ultimately a false dichotomy. But even if she was able to conclude that reforms could still be pursued within the framework of a revolutionary program – i.e., without falling into reformism – this was by no means an obvious position to take.

Still less should we consider the matter done and settled with respect to our current context simply because a great figure like Luxemburg dealt with it in her own day. We do not have the luxury of resting on the accomplishments or insights of past thinkers. It is unclear whether the solution at which she arrived holds true any longer. History can help us understand the momentum of the present carried over from the past, as well as possible futures toward which we may be heading. But history offers no prefabricated formulae for interpreting the present, no ready-made guides to action.

The difficulties in relating these three concepts – reform, revolution, and resistance – cannot be avoided by invoking a “diversity of tactics.” Each of them ostensibly refers to an overarching strategy for achieving emancipation and thus cannot be reduced to a mere selection of tactics. It is uncertain whether the activity (or passivity) of resistance ever even attains the level of a conscious strategy, much less tactics. In Foucault’s metaphysics of power, resistance is an unconscious, automatic, and reflexive response to power relations wherever they exist. “Where there is power, there is resistance,” claims Foucault. As a statement, however, this says nothing of the world as it ought to be, or how such a world might be brought into existence. At most, it only describes a fact of being,1 inside of institutionalized power structures.

But perhaps all this already assumes too much. The more fundamental question that presently confronts us is: what do resistance, reform, and revolution even mean today? Each of these concepts arose historically in connection with concrete processes and events. These are hardly perennial categories reaching all the way back to the dawn of time; indeed, the oldest among them is only as old as the Left itself. A review of the contexts in which these concepts crystallized may help clarify their bearing on the present. Tracing the origins of a concept’s modern usage should not be thought of as a way to recover its “authentic” meaning. However, if substantial shifts have taken place in conceptualizations of reform, revolution, or resistance, we should be honest about any such departure.

This is especially true with the category of revolution, which has undergone the most significant renovation in Occupy discourse. If reform was the most problematic figure of thought for Luxemburg in 1900, and resistance for Platypus five years ago, then the most pressing concept in need of clarification for the Left now is revolution. Of course, if former conceptions of revolution prove to be inadequate or unrealistic today we are not forbidden from using the word. But we should at least be clear about the historic break, so as to not act like we’re somehow remaining loyal to a good old cause.

Resistance

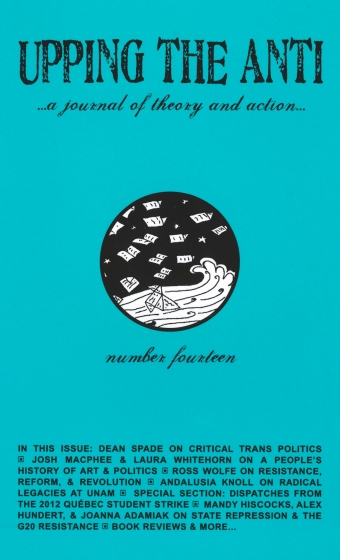

Of the three terms presently under investigation, “resistance” is the one of most recent vintage, at least to the extent that it has been conceptualized and self-consciously used on the Left. Some preliminary remarks will help to focus the discussion. As Stephen Duncombe pointed out a few years ago, the concept of resistance can be inherently conservative: it indicates the ability of something to maintain itself – to conserve or preserve its present state of existence – against outside influences that would otherwise change it.2 Thus, resistance signifies not only defiance but also intransigence. As the editors of Upping the Anti put it a couple of years ago, resistance automatically assumes a “defensive posture.”3 It thus appears to be politically ambivalent: it depends on what is being conserved and what is being resisted. Historically, the language of resistance was linked with conservatism. At least, this is how recalcitrant elements of society have understood their opposition to the Left ever since its inception in 1789. Against the rationalism and excesses of the French Revolution, the British statesman and archconservative Edmund Burke praised England for its stubborn resistance to radical projects of political modernization. He wrote:

Thanks to our sullen resistance to innovation, thanks to the cold sluggishness of our national character, we still bear the stamp of our forefathers…We are not the converts of Rousseau; we are not the disciples of Voltaire; Helvétius has made no progress amongst us…We fear God; we look up with awe to kings; with affection to parliaments; with duty to magistrates; with reverence to priests; and with respect to nobility.4

As late as 1848, the term resistance was chiefly deployed by reactionaries. Under the July Monarchy, conservatives founded le Parti de la Résistance against the more progressive Parti du mouvement. The forces of reaction in Europe were not merely content to resist revolution, however. Later, in the struggle for electoral reform in Britain in the 1830s, the Left once again had to contend with the resistance of conservative legislators.5

Only in the 20th century did resistance come to be associated with leftist politics, by virtue of a threefold historical development. First, it was ennobled through movements of opposition by colonial peoples in resisting imperial subjugation. But even here, the emancipatory character of resistance to imperialism was not always clear-cut. Vladimir Lenin, whose theory of imperialism is commonly invoked by Marxists today, was wise enough not to offer unqualified support to just any movement “resisting” imperialist aggression. Lenin argued against the Left cheering on uprisings against imperialism led by regressive social elements in the absence of progressive alternatives.6

The concept of resistance was romanticized yet further through the experience of La Résistance in France fighting the collaborationist Vichy regime. Quite a few of the resistance’s most prominent heroes and martyrs belonged to the Communist movement. Even this case was not without its problems, however. The French Communists’ much-touted resistance to fascist rule bore throughout the indelible imprint of Stalinist pop-frontism. As some perceptive Trotskyist critics noticed already in 1939, the strategy of the Popular Front siphoned off revolutionary energy from the more militant sections of the French labour movement by diverting them into mindless campaigns of coalition building.7

Finally, in the hands of postmodern and postcolonial theory, resistance received authoritative academic stamps of approval. It became consecrated as the standard mode of dissent under late capitalism. To provide just one example of the kind of needlessly baroque theoretical explanations given to resistance by postcolonialists, we need only look at Homi Bhabha’s 1994 work on The Location of Culture:

Resistance is not necessarily an oppositional act of political intention, nor is it the simple negation or exclusion of the “content” of another culture, as a difference once perceived. It is the effect of an ambivalence produced within the rules of recognition of dominating discourses as they articulate the signs of cultural difference and reimplicate them within the deferential relations of colonial power – hierarchy, normalization, marginalization and so forth.8

For all his obscurity, Bhabha at least elucidates an apolitical form of resistance. What is unclear from his explanation is whether a subject can actively “resist” forms of foreign cultural domination “in order to preserve the authority” of more familiar, traditional, or “indigenous” forms of domination.

It is necessary to understand postcolonial theory within the context of the Cold War politics from which it emerged. With the decline of revolutionary leftist politics in the most industrialized nations of the world, hopes for radical social transformation migrated to what the French demographer Alfred Sauvy dubbed the Third World.9 These hopes eventually reached their ideological apotheosis in what has come to be known as “Third-Worldism.” In the global system divided into blocs between the First World (the US and its allies) and the Second World (the USSR and its allies), the primary site of political struggle shifted to the Third World (the non-affiliated countries, which were often ex-colonies of European nations).

Ironically, such sentiments often survived the actual ideologies that engendered them. Enthusiasm for national liberation movements in formerly colonized regions continued in Western activist circles long after the USSR and PRC in the East ceased funding them – the former following its dissolution in 1991, the latter after the coup d’état that overthrew the Gang of Four in 1976. At this point, the streams of postcolonialism (arising from capitalism’s periphery) and postmodernism (arising from its core) converged.10 All the grand narratives of the past, it seemed, had collapsed. Edward Said’s Orientalism came out in 1978; Jean-François Lyotard’s Postmodern Condition was released a year later. Both works are seminal within the postcolonial and postmodern canons, respectively. Significantly, postcolonialism and postmodernism may be regarded as an outcome of the practical exhaustion and theoretical confusion brought on by the failure of the New Left. Tired, disillusioned, and largely depoliticized, many New Left radicals joined the very institutions they once opposed as full-time academics or professional activists.

The transformation of a large segment of the New Left into the self-proclaimed “post-political” or “post-ideological” Left placed a new premium on the concept of cultural resistance.11 Already by the late 1970s, postcolonialism and postmodernism’s most valuable contributions to radical politics already belonged to the past. The Albert Memmi of The Colonizer and the Colonized and the Frantz Fanon of Black Skin, White Masks (not The Wretched of the Earth)12 were vastly preferable to today’s figures, like Homi Bhabha or Dipesh Chakrabarty. The same can be said of postmodernism. Lyotard the member of Socialisme ou Barbarie was more interesting than Lyotard the relapsed Kantian aesthetician; the Jean Baudrillard of The Mirror of Production deserves to be prioritized over the author who later wrote Simulacra and Simulation. Either way, postcolonial and postmodern politics typically didn’t aspire to much beyond resistance toward the seemingly all-powerful forces of neoliberalism and globalization.13

Such is the genealogy of resistance in the vicinity of the Left. Last fall in New York’s Liberty Plaza, one could regularly see signs that read (in a perverse Cartesianism): “I Resist, Therefore I Exist.” The efficacy of such resistance is questionable, however. Recently, Marxian theorists such as Moishe Postone and Slavoj Žižek have suggested that a politics based on resistance is often unwittingly complicit with the very systems it purports to resist.14 It remains unclear, moreover, how resistance fits into any broader emancipatory program. As Chris Cutrone observes: “the Left today almost never speaks of freedom or emancipation, but only of ‘resistance’ to the dynamics of change associated with capital and its transformations.”15

Of course, this is not to deny any and all emancipatory power to acts of resistance. But resistance can really only be called upon to preserve or marginally extend those freedoms of which one already possesses, against the forces that seek to limit them. In this sense, the politics of resistance do not go beyond the “right of resistance” proclaimed by early liberals such as John Locke, who in his Second Treatise on Government wrote that “they who use unjust force may be questioned, opposed, and resisted.”16 An extension of inalienable bourgeois property, one possessed the right to protect his or her own “life and limbs.”

Reform

In its modern sense, “reform” stretches back quite a bit further, although this should not be extended to the point of anachronism. One might be tempted, for example, to include the Magna Carta in the history of reforms. It should be remembered that the king’s concession to the feudal barony was not obtained through established legal channels, but at the tip of a sword.

While the history of successful, sweeping reforms begins in Britain with the Great Reform Act of 1832, demands for reform had a significant prehistory. Originally, the meaning of reform, stricto sensu, was specifically related to matters of enfranchisement – “an extension of the electorate.”17 The earliest calls for parliamentary reform, in the decades following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, pertained to widespread political corruption. In 1776, the radical parliamentarian John Wilkes first advanced a proposal for universal male suffrage, largely as a reaction to the American War of Independence.18 Nevertheless, such daring calls for democratization were highly anomalous at this point.

Clamouring for reform rapidly accelerated in the aftermath of the French Revolution of 1789, however.19 Another great proponent of “radical” reform was the famous utilitarian philosopher, Jeremy Bentham. Even following Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo, on the eve of the Restoration, he posed the same disjunction Luxemburg would make 80 years later, albeit in a quite different register: “the country… is already on the very brink – reform or convulsion, such is the alternative.”20 Bentham barely lived to see the first fruits of such struggles for reform. The Great Reform Bill of 1832 granted broader voting rights to British adult males, at least in principle. Popular pressure for reforms came in large part from the nascent labour movement. Despite its successful passage, many of its supporters believed that these reforms had not gone far enough. The Chartist movement grew out of this overwhelming sense of dissatisfaction and persecution.21 Immediately following the enactment of the 1832 Bill – the foundational act in the history of modern reform – the terrain on which the battle for reforms was waged shifted. Reforms no longer centred exclusively on the issue of suffrage. Fresh on its heels came the Factory Act of 1833. Over the course of the next 30 years, the working class in Britain fought for the institution of regular limits to the working day. This was the struggle described in riveting detail by Karl Marx in Capital.22

Within the context of international Social Democracy, the struggle for reform was not conceived as separable from the goal of revolution until the end of the 19th century. The crisis of Second International Marxism that occurred during the Revisionist Debate of the 1890s was itself symptomatic of its success in building a popular movement. In other words, Eduard Bernstein’s contention that the working class could best realize its emancipation through a progression of social reforms23 had itself been precipitated by the movement’s strength in achieving parliamentary representation and the very real threat of revolution. It only became possible through the further articulation of working class politics in the years after Marx’s death. Reform, as Luxemburg argued, is not so much the antithesis of revolution as it is its practical form. The fact that reforms are even possible indicates that revolution may be on the table.

However, the gains made through social reforms by the merging of European Social Democracy, which drifted gradually rightward following 1917, and liberalism, drifting leftward in Keynesian guise after 1933, are presently deteriorating under cutbacks: “The abandonment of emancipatory politics in our time has not been, as past revolutionary thinkers may have feared, an abandonment of revolution in favor of reformism,” Spencer Leonard recently observed. “Rather, because the revolutionary overcoming of capital is no longer imagined, reformism too is dead.”24 Political events over the course of this last year seem to confirm Leonard’s judgment. The faint murmurs that were heard early on in Occupy movement protests, which called for the reinstatement of Glass-Steagall or the creation of a “Jobs for All” program, have all but subsided. Placards later appeared stating that “Capitalism cannot be reformed.”

True enough. But what would reform even look like now that the Left is in retreat? Are the austerity measures in Europe, one wonders, “reforms”? Bank bailouts and deregulation? Rescinded pensions and mass layoffs? Or has the fight for reforms instead moved toward a totally different modality of engagement, becoming a purely defensive battle to uphold the reforms of the past against the neoliberal onslaught? Must the struggle for new reforms be put on hold, if not abandoned completely? And are we really obligated to defend the last miserable scraps of the welfare state – the gutted remains of social programs begun over 60 years ago? Today, the options of “reform or revolution” seem to have been supplanted by the inevitability of “deformation and devolution.”

Revolution

If today the question of reform has once again entered into crisis, this is because the concept of revolution has lost its self-evidence. Luxemburg’s rejoinder to Bernstein steadfastly asserted that “the conquest of political power has been the aim of all rising classes.”25 And while Trotsky could categorically claim in 1924 that “y [revolutionary] strategy, we understand the art of conquest, i.e., the seizure of power,”26 it is not at all clear that this is still the case. The Occupy movement has, by contrast, largely followed the strategy formulated by the Marxian autonomist John Holloway in 2002, to “change the world without taking power.” The subtitle to Holloway’s book says it all: “the meaning of revolution today.”27

As with resistance and reform, the modern concept of revolution arose historically and should not be elevated into a trans-historical principle simply because of its venerable status in leftist political discourse. Revolution was born alongside the Left itself, as its conceptual twin. William Sewell has perhaps contributed the most to understanding this historical dimension of revolution:

We are by now used to the notion that revolutions are radical transformations in political systems imposed by violent uprisings of the people. We therefore don’t see the extraordinary novelty of the claim that the taking of the Bastille was an act of revolution. Prior to the summer of 1789, the word revolution did not carry the implication of a change of political regime achieved by popular violence… In ordinary parlance… the “uprising” or “mutiny” of July 14th could… be designated by contemporaries as a “revolution,” but this was… not because it was a self-conscious attempt by the people to impose by force its sovereign will.28

For Sewell, the concept of revolution – at least in its modern meaning – designates a momentous and irrevocable event: “[E]vents should be conceived of as sequences of occurrences that result in transformations of structures,” he explains. “Such sequences begin with a rupture… [and] durably [transform] previous structures and practices.”29 Any revolution worthy of the name would thus seem to require a radical discontinuity with the past – “blasted out of the continuum of history,”30 as it were. This would involve a compressed temporality. Lenin is said to have quipped that “there are decades where nothing happens; there are weeks when decades happen.” Revolution, in this model, would then necessarily hinge upon certain decisive moments: “turning points,” “breakthroughs,” “tipping points,” “points of no return,” “starts and fits” – moments after which nothing was ever the same, after which there was no going back. Removing these moments from a revolution would mean “reducing… [it] to [the] vague notion of a slow, even, gradual change, [with an] absence of leaps and storms.”31

Of course, a revolution cannot be accomplished in one fell swoop. At a certain level, there must be a dialectic between process and event involved in any truly revolutionary transformation. “The international revolution,” Leon Trotsky reminded us, “constitutes a permanent process, despite temporary declines and ebbs.”32 Nevertheless, Trotsky was always sure to stress the unevenness of this process. “Historic processes [hardly consist of] a steady accumulation and continual ‘improvement’ of that which exists. [History] has its transitions of quantity into quality, its crises, leaps, and backward lapses.”33 Certainly, some continuity with the world before the revolution will remain, but there will be important discontinuities as well.

The understanding of “revolution” just sketched can be usefully contrasted with that of David Graeber, whose thought has undeniably served as one of Occupy’s greatest sources of inspiration. Graeber provides the clearest expression of revolution as a kind of continuous, never-ending process unpunctuated by events. Accordingly, he rejects the notion of history as marked by qualitatively distinct “epochs”:

[T]here has been no one fundamental break in human history. No one can deny there have been massive quantitative changes: the amount of energy consumed, the speed at which humans can travel, the number of books produced and read [but] these quantitative changes do not… necessarily imply a change in quality: we are not living in a fundamentally different sort of society than has ever existed before, we are not living in a fundamentally different sort of time.34

In Graeber’s opinion, the mistake underlying these conceptions of revolution as rupture consists in their Lukácsean assumption that abstractions like “capitalism” or “society” exist as real totalities. “[T]he habit of thought which defines … society as a totalizing system,” Graeber argues, “tends to lead almost inevitably to a view of revolutions as cataclysmic ruptures.”35 In place of this more traditional version of what revolution may look like, Graeber instead advocates a “prefigurative” politics of creating a microcosm of the society one would want to live in. This notion is not wholly without precedent: echoes can still be heard of the old motto from the 1905 IWW Preamble, which prescribes “forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old.” Not all anarchists look to create models of prefiguration, however.

Among the Occupy movement’s insurrectionist tendencies, the French pamphlet on The Coming Insurrection still holds some weight. With its paramilitary pose and radical chic, its knowing matter-of-factness, the rhetoric from this mini-manifesto remains fashionable in some circles. The book refrains from glamorizing violence as such, but much of its appeal clearly comes from its literal call to arms: “There is no such thing as a peaceful insurrection. Weapons are necessary.”36 The Coming Insurrection still pales in comparison to the bellicosity of past works from the anarchist canon (insofar as there is one). Certainly, anyone who has read the terrifying Catechism of a Revolutionary, co-authored by Mikhail Bakunin and Sergey Nechaev in 1870, will look back at The Coming Insurrection as mere child’s play. Still, there are traces of the old revolutionary notion of irreversibility in the Invisible Committee’s “insurrection.” Nevertheless, the imagination of The Coming Insurrection is for the most part limited to the experience of the 2005 riots in the Paris banlieues, which were scattered, largely local affairs. World revolution is nowhere to be found in its pages.

It should be emphasized that these concepts of revolution depart not only from most of those passed down by Marxist theory through the ages, but also from the majority of anarchist ideas concerning revolution prior to 1968. Giants of revolutionary anarchism like Bakunin, Nechaev, and Errico Malatesta each adhered to the vision of a massive, sudden uprising, a simultaneous break with the past taking place on a worldwide scale.37 Some, like Paul Brousse and Johann Most, advocated the “propaganda of the deed” – i.e., acts of spectacular terrorism – hoping to spur the masses to spontaneous action. Peter Kropotkin understood revolution as “synonymous with… the toppling and overthrow of age-old institutions within the space of a few days, with violent demolition of established forms of property, with the destruction of caste, with the rapid change of received thinking.”38 One would be hard pressed to find any revolutionary program coming out of the Occupy movement with such ambitious scope or intensity.

Such departures from the way revolution was previously understood should not be thought unacceptable, of course. Trying to hold anyone, let alone an anarchist, to the authority of past thinkers would be an exercise in futility. The real question, it seems to me, is the following: what does it say about our own political moment that such past conceptions of revolution seem so outlandish, impossible, and unthinkable to us today? Were yesterday’s notorious revolutionaries simply deluded, mistaken, and misguided? Or is it rather that we stand on political ground that is considerably worse than theirs? Do we perhaps today inhabit a world in which politics has regressed substantially from the historical position it held a century ago?

Reflections

Having discussed these three terms in relative isolation from each other, it is only appropriate to reflect on how they might fit together to form a politics of the present. In so doing, however, a fourth figure of thought arises: that of emancipation. Resistance, reform, and revolution are only meaningful to the extent that they realize emancipation as their ends. Depending on the concrete contexts in which they move, different strengths and weaknesses are revealed.

Earlier this year, the Middle East specialist Charles Tripp addressed recent examples of resistance in his talk on “The Politics of Resistance and the Arab Uprisings.” Tripp’s lecture looked back on the spectacular success of coordinated non-cooperation and the occupation of public spaces in Egypt and Tunisia over the course of the preceding year. The kind of resistance he discussed was for the most part of a nonviolent nature, excepting, of course, such spectacular acts of suicide as the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia. For Tripp, the primary mode of political struggle in scenarios of resistance is “the symbolic order” – parade grounds and public spaces that symbolize the power or “hegemony” of a regime. Through public demonstrations and “embodied” expressions of discontent, Tripp argued, the symbolic order propping up such dictators like Ben Ali or Mubarak was delegitimated, subverted, or otherwise disturbed. Once overthrown, it seemed, the actual governments soon followed.

Undoubtedly, the success of the more or less spontaneous mobilizing of a “politics of resistance” in Egypt, Tunisia, and Bahrain was nothing short of miraculous. Indeed, despite the forms of resistance that subsequently took shape across Europe and North America amidst the widespread political radicalization of 2011, none achieved such significant victories as those won early on in the Arab Spring. Nevertheless, lurking in the background of Tripp’s talk were the far more troubling examples of Libya and Syria, where popular resistance to the established authorities and violence against the symbolic order were met with gunfire and government reprisals. After these initial skirmishes, opposition to the regimes assumed a very different form than in Egypt, Tunisia, or Bahrain, becoming armed resistance.

As pockets of resistance expanded, however, battle lines were drawn. Here it was no longer appropriate to speak of the opposition to Muammar Gaddafi or Bashar al-Assad as mere resistance, as this usually suggests the existence of an underground, with groups carrying out secretive operations in seclusion from one another. With (as in Libya) or without (as in Syria) the blatant intervention of outside forces like NATO, the regular and irregular soldiers joining arms against government forces now constituted an army of liberation. The goals they pursued were not limited to sabotage, misinformation, disruption, or defiance, as had been the case before. Asymmetrical combat zones and urban warfare may still have been fairly common in Libya after July 2011, but a telling semantic shift took place at this point. Armed resistance against the regime rapidly escalated into full-blown civil war – a revolution, at least on a national scale. Once forced onto their heels, the loyalists to Gaddafi holed themselves up in his hometown of Sirte. There they were maintained as “pockets of resistance.” The tables had turned.

Reforms, which are seldom as spectacular as revolutions or as edifying as daily resistance against domination, have been relatively few and far between in the past few years. Some victories have been achieved, while some major defeats have gone unnoticed. It is telling to note where the defeats and the victories have come from, as well. The issue of reforms remains undecided in the context of the Arab Spring. Most of the states whose old regimes have been replaced are currently in the process of drafting a new constitution, or have only just recently held elections. Egypt is still the only country in which a government has been elected, and even then the results are far from sunny: the threat of a military coup hangs over its parliament, and should the threat be removed, it is still unclear whether the representatively dominant FJP (the partisan wing of the Muslim Brotherhood) will enact progressive reforms that will promote gender equality and tolerance for religious minorities. They are unlikely to decriminalize homosexuality or recognize alternative sexual lifestyles any time soon.

Still, the broader reason that reforms have not already been instituted in the region is that revolution broke out mostly in countries where the existing rulers refused to entertain the possibility of reform. The revolutionary agitation, which called for the dissolution of stifling dictatorships, and the armed conflict that commenced against the state, came after popular appeals for reform had been denied. In countries where the old regime collapsed, the most basic reforms that have been put in place to date pertain to the establishment of legitimate electoral procedures. Further reforms are pending, for now.

Relatively speaking, however, advocacy for measures that would extend government social programs or introduce universal health care has met with far more mixed results. In Europe, the welfare state – the crown jewel of nearly a century of Social Democracy – is unraveling at an alarming rate. The victory of the teachers’ union in Chicago against legislation that would impose stricter vetting procedures for teachers is heartening, to be sure, but it remains unclear whether this victory constitutes a “reform.” It seems better classified as a successful instance of resistance against a proposal that would worsen their situation further, rather than push for a measure that would improve it. This is despite the increased salaries they won through their renegotiated contracts, which can hardly be written off as insignificant.

Resistance, reform, and revolution all aim toward what Marx called the solution to “the riddle of history”: communism. To date, however, this riddle remains unsolved. In the absence of a viable, international popular movement that could potentially overcome the rule of capital, answers are in short supply. Until such a movement is constituted, the only available options are micro-resistance, piecemeal reforms, and local/national revolutions – while the realization of total social and individual freedom is forestalled. H

Notes

1. Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction. (Pantheon Publishers. New York, NY: 1978). Pg. 95.

2. Duncombe, Stephen. “The 3 Rs: Reform, Revolution, and ‘Resistance’: The Problematic Forms of ‘Anticapitalism’ Today.” The Platypus Review, 4. (New York, NY: April, 2008).

3. “With Eyes Wide Open: Notes on Crisis and Resistance Today.” Upping the Anti, 10. (Toronto, ON: May, 2010).

4. Burke, Edmund. Selected Works, Volume 2: Reflections on the Revolution in France. (Liberty Fund. Indianapolis, IN: 1999). Pg 180.

5. Paul, Alexander. The History of Reform: A Record of the Struggle for the Representation of the People in Parliament. (George Routledge & Sons. New York, NY: 1884). Pg. 138.

6. Lenin, Vladimir Il’ich. “A Caricature of Marxism and Imperialist Economism.” Translated by M.S. Levin, Joe Fineberg, and others. Collected Works, Volume 23: August 1916-March 1917. (International Publishers. New York, NY: 1964). Pg. 63.

7. Spector, Maurice. “The Popular Front’s Guilt.” New International. (Vol. 4, 11: November 1938). Pg. 329.

8. Bhabha, Homi. The Location of Culture. (Routledge. New York, NY: 1994). Pgs. 110-111.

9. Sauvy, Alfred. “The Third World.” Translated by Christophe Campos. General Theory of Population. (Basic Books. New York, NY: 1969). Pgs. 204-218.

10. Cutrone, Chris. “The Relevance of Lenin Today.”

11. Said, Edward. “At the Rendezvous of Victory.” Culture and Resistance: Conversations with Edward W. Said, Inteviewed by David Barsamian. (South End Press. Cambridge, MA: 2003). Pg. 159.

12. Singh, Sunit. “Book Review: Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks.” Platypus Review.

13. Buck-Morss, Susan. “Postcolonialism or Postmodernism? An Interview conducted by Chris Mansour.” Platypus Review.

14. Postone, Moishe. “History and Helplessness: Mass Mobilization and Contemporary Forms of Anticapitalism.” Public Culture. (Vol. 18, 1: 2006). Pg. 108.

15. Žižek, Slavoj. The Ticklish Subject: The Absent Centre of Political Ontology. (Verso Books. New York, NY: 2000). Pg. 262.

16. Cutrone, Chris. “The 3 Rs: Reform, Revolution, and ‘Resistance’.”

17. Locke, John. Second Treatise on Government. (Cambridge University Press. New York, NY: 2003). Pgs. 402-403; 207.

18. Paul, Alexander. The History of Reform: A Record of the Struggle for the Representation of the People in Parliament. (George Routledge & Sons. New York, NY: 1884). Pgs. 1-2.

19. Ibid., pgs. 16-19.

20. Ibid., pgs. 61-62.

21. Bentham, Jeremy. “Plan of Parliamentary Reform, in the form of a Catechism, Showing the Necessity of Radical, and the Inadequacy of Moderate, Reform.” Collected Works, Volume 3. (Oxford University Press. New York, NY: 2012). Pg. 433.

22. “The Whigs’ Reform Act of 1832 extended the electoral franchise to a good section of the middle class, but the working class, who supported the Whigs’ Reform agitation, remained excluded from the franchise.” Black, David. “The Elusive ‘Threads of Historical Progress’: The Early Chartists and the Young Marx and Engels.” No. 36. (December 2011-January 2012).

23. Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1. Pgs. 389-411.

24. Bernstein, Eduard. The Preconditions of Socialism. Translated by Henry Tudor. (Cambridge University Press. New York, NY: 1993). Pg. 186.

25. Leonard, Spencer. “The Decline of the Left in the Twentieth Century: 2001.” Platypus Review, 17. (November 18th, 2009). Pg. 2.

26. Luxemburg, Rosa. Reform or Revolution? Translated by Integer. (Haymarket Books. Chicago, IL: 2008). Pg. 89.

27. Trotsky, Leon. Lessons of October. Translated by John G. Wright. (Bookmarks. London, England: 1987). Pg. 16.

28. “Holloway, John. Change the World without Taking Power: The Meaning of Revolution Today. (Pluto Press. Ann Arber, MI: 2010). Pg. 20.

29. Sewell, William. “Historical Events as Transformations of Structures: Imagining the Revolution at the Bastille.” Logics of History: Social Theory and Social Transformation. (The University of Chicago Press. Chicago, IL: 2005). Pg. 235.

30. Ibid., pg. 227. My emphasis.

31. Benjamin, Walter. “On the Concept of History.” Translated by Edmund Jephcott. Selected Writings, Volume 4: 1938-1940. (Harvard University Press. Cambridge, MA: 2003). Pg. 395.

32. Lenin, Vladimir. “The State and Revolution: The Marxist Theory of the State and the Tasks of the Proletariat in the Revolution.” Translated by Stepan Apresyan and Jim Priordan. Collected Works, Volume 25: June-September 1917. (International Publishers. New York, NY: 1974). Pg. 401.

33. Trotsky, Leon. “The Permanent Revolution.” Translated by John G. Wright and Brian Pearce. The Permanent Revolution & Results and Prospects. (Pathfinder Press. New York, NY: 1978). Pg. 133.

34. Trotsky, Leon. The Revolution Betrayed: What is the Soviet Union and Where is it Going? Translated by Max Eastman. (Pathfinder Press. New York, NY: 1983). Pg. 48.

35. Graeber, David. Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology. (Prickly Paradigm Press. Chicago, IL: 2004). Pg. 50.

36. Ibid., pgs. 43-44.

37. The Invisible Committee. The Coming Insurrection. (Semiotex(t)e. 2006). Pg. 84.

38. Bakunin, Mikhail. Revolutionary Catechism. Translated by Sam Dolgoff. Bakunin on Anarchy. (Vintage Books. New York, NY: 1972). Pg. 96.

39. Kropotkin, Peter. “Revolutionary Government?” Translated by Paul Sharkey. No Gods, No Masters. (AK Press. Oakland, CA: 2005). Pg. 313.