Indigenous Sovereignty Fuels Pipeline Resistance

An Interview with Freda Huson and Toghestiy of the Unist’ot’en Camp

When Canada’s fossil fuel industry launched an aggressive plan to turn the country into a major energy exporter and triple tar sands production by 2030, few of its supporters could have foreseen the Indigenous-led resistance that has now delayed or blocked almost every proposed mega-pipeline. Grassroots organizing in British Columbia has thus far frustrated efforts by industry and government to build pipelines to the Pacific coast. These pipelines, by facilitating export of the dirtiest fuels on the planet to international markets, would allow Canada to massively expand its tar sands and LNG (liquefied natural gas) industries.

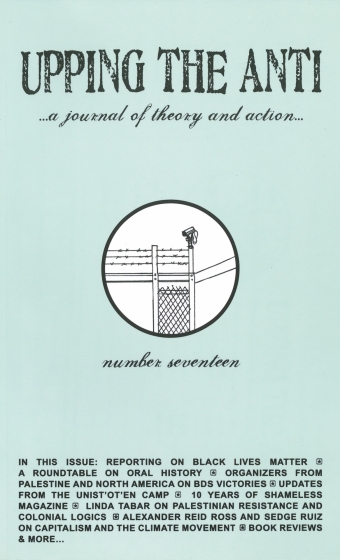

The Unist’ot’en Camp, situated in Northwest BC, stands out as an uncompromising site of resistance to pipelines and to colonization. It is a community determined to protect sovereign Wet’suwet’en territory from several proposed tar sands and fracked gas pipelines. Established in 2009, the Camp is one of the continent’s longest-running active blockades. Supporters have built cabins, pithouses, and permaculture gardens directly on the GPS coordinates of several proposed pipelines. They enforce a Consent Protocol that determines who is allowed access to the area, and have evicted pipeline crews found working on Wet’suwet’en territory several times. Pipelines being blockaded include Enbridge’s Northern Gateway, Chevron’s Pacific Trails, and TransCanada’s Coastal GasLink and Prince Rupert projects.

Freda Huson and Toghestiy, Wet’suwet’en land defenders and representatives of the Camp, live permanently on the blockade. Freda (Unist’ot’en Clan) is spokesperson of the Camp, and Toghestiy is a hereditary chief of the Likhts’amisyu Clan. Amani Khalfan interviewed them in October 2014.

Could you put the Unist’ot’en struggle against pipelines in context? What sort of industry has impacted your territories most? Who and what has been affected?

Toghestiy: I wrote a report for the Unist’ot’en about five years ago explaining the cumulative impact of industry on our territories. It started way back when the Unist’ot’en as well as the other Wet’suwet’en were forcibly removed from the territories and put onto Indian reserves. There was a forced disconnection from the land that was really tough because a lot of family members didn’t make it. They either froze or starved to death. We weren’t allowed off those reserves, so we had to find ways to survive there. Before contact, our people thrived and had a lot of food and health benefits from being out on our traditional lands. Reserves were the first big impact and they blazed the way for industry to make its way into the territories. Not long thereafter, small logging camps started to open up, and the railroad came in.

Eventually in 1952 there was a hydroelectric project slated for Kitimat, called the Kemano Project. There’s a huge man-made lake that spans the southern part of the Wet’suwet’en territories called Ootsa Lake. The company dammed the entire area and flooded a massive span of land that belonged to the Unist’ot’en. They drilled a massive tunnel through a mountain, and the water in the reservoir flowed through the tunnel to turn giant turbines, which generated electricity for the Alcan aluminium smelter. Through that process, the Wet’suwet’en Nation lost a massive caribou herd that used to migrate down into Secwepemc country near Kamloops and north through Wet’suwet’en territory up into Gitxsan territory. All the caribou drowned when they were trying to cross over the reservoir following their migratory routes. Up until 1952, caribou was our staple food.

After that, mining, agricultural, and logging companies began to create a huge footprint on the land. Settlers migrated in by the hundreds, establishing homesteads that were initially cleared by Wet’suwet’en people; they basically kicked Wet’suwet’en families out of their homes, killed their cattle, burnt their buildings down, and took over the land.

More recently the small logging and mining companies have begun to amalgamate and create bigger projects. Now we have one really big logging company in Wet’suwet’en territories, the Canfor forest company. Our people have been impacted by mining companies destroying watersheds. One of the big ones was the Equity Silver Mine disaster in 1984 when a tailings pond burst and wiped out a huge salmon run that used to make its way up close to Freda’s dad’s territory.

We’ve also faced a lot of agricultural expansion. Grazing leases were handed out to farmers to bring their cattle out, and eventually these farmers fenced off a large area of the bush and converted that into private land. The Ministry of Forests and the Ministry of Environment handed over this land to the farmers because they invested so much time and energy into it. Because of that, quite a few people are landowners of Wet’suwet’en territory. There was no consultation with the people at all. Even today, the Ministry of Forests is facilitating landowners in taking massive swathes of unceded Wet’suwet’en land. Even if we challenge them, they continue to hand out permits.

More recently we’re dealing with pipeline companies. Fracking pipelines and bitumen pipelines are being proposed to bulldoze their way right through our territories. Our people are all facing up to them. And that’s where Freda and her Clan stepped up.

You have said that people always ask you how you became activists or environmentalists, but that you’re not – you’re traditionalists. What is traditionalism and how does this approach influence your strategies and actions?

Freda: We grew up this way, as traditionalists, learning how to only take what you need and how to always give back – industry doesn’t do that. Logging companies have clear-cut massive sections and actually tripled their allowable cut. They use these machines that just tear up the ground. They say, “Well, logging is a renewable resource because we plant trees back.” But they only put back the species that they plan to cut down again, like balsam, spruce, and pine.

It’s quite dry and the soil is dead every where they’ve clear-cut. The same vegetation doesn’t grow back. The whole ecosystem is out of balance because of it. It impacts all the animals; we’ve noticed there are fewer and fewer of certain species and when some of the forests are allowed to grow back, you see these species start resurfacing again. Then the company comes along and does more clear cutting.

Our people have always used all our territories according to the seasons. For our salmon, we went back to the home community where we grew up to do our fishing. Certain areas are more plentiful with moose, so we usually ran our hunting camps in one of our other territories. And this area that we’re protecting from the pipelines is one of the best for trapping. Each of our territories had a specific purpose, and we still practice that today.

Our berry picking has been impacted because clear cutting wipes out our medicines and berry patches. As Toghestiy mentioned, farmers and ranchers branch out on to territories where we normally hunt. They’ve put up fences that say ‘no trespassing’ and they have cattle guards everywhere so the moose can’t roam freely anymore. They’ve clear-cut a lot of the areas and now there’s grass there. So more and more, it’s looking like farmland when it’s supposed to be forest. That causes an imbalance for the atmosphere too, and the lake is not the same. We should be able to drink out of the lake but now we can’t because the cattle have polluted it.

At what point did you decide that it was necessary to start living on the blockade, in the path of the pipelines?

Freda: It was probably five years ago when we started talking about our concerns and saying we had to do something. We put up the cabin, but nobody was actually living here and we were finding we couldn’t effectively monitor our territory. My dad always said that the strongest thing that you can do is to actually occupy, to show that you’re still using that land – and then they won’t be able to remove you because it’s not just a blockade. We’re actually living here, and we’re occupying our land and reclaiming our responsibility.

Even now we’re practicing conservation; we’re not allowing hunters in. We’re trying to let the population replenish, then once there are a lot more moose we can open up again – maybe to our people and not to the general public, because our people are having a hard time finding moose. Everybody else’s staple food is beef and chicken; our staple food is fish, moose, deer, and everything we get off the land.

Toghestiy: Another thing we noticed over the past few months is a herd of caribou that were reintroduced to Wet’suwet’en territory. They were transplanted in the mountain range north of us as an experiment, and they’re doing well now. We actually sighted some

caribou in the back of the territory behind the blockade. It’s the first time we’ve seen caribou in this part of Wet’suwet’en territory since before 1952. We know that if we let the hunters in somebody might accidentally shoot one of them and we don’t want that to happen, so we decided to close it off this year.

processed food everybody eats. If the weather doesn’t cooperate and the land has been impacted so much that all the vegetation dies, what will the animals eat?

Toghestiy: There are a lot of prophecies around the world, especially on Turtle Island, about this. The Wet’suwet’en have a prophecy about what’s to come. We have one significant glacier that sits right in the middle of our territories, and the prophecy says that when that glacier melts away, the earth will catch on fire. Our people need to be prepared if we’re to survive. That’s always in the back of our minds. We’re always thinking, how are we going to prepare for surviving in really rough conditions? How do we put seed away? How do we put food away? How do we store water? Where are some places of refuge?

That’s exactly what we’re doing here; we’re preparing. Our ancestors survived the Great Depression; we had no idea that the Great Depression was even here until the settlers started showing up at our doorsteps. Our people who survived the first couple of decades on Indian reserves began to thrive again because we were survivors.

Freda: More and more people are talking about doing the very thing we’re doing, because they’re realizing that it is actually working. When we stayed confined in the prison of the reserves, industry was continuing business as usual. Since we reoccupied, people have to ask our permission to come onto the territory. But people still freely come and go on our other territories because we only can fight one battle at a time.

On the bridge over the [Wedzin Kwah] River that leads to this territory we have a sign that says “No access without consent.” We don’t give people permission to come in unless they answer a series of questions: who they are; why they are here; how long they plan to stay; whether they work for industry or government that’s destroying our lands; and how their visit will benefit our people. That last one is key. If it won’t benefit our people and if it will negatively impact our lands, we’re not going to permit entry.

We were hoping that once we showed people we could do this successfully, others would join us. Right now we have a neighbour 40 minutes drive from us who has moved into a cabin and is doing what we’re doing. They’re trying to protect their territory from a tailings pond and mine that’s proposed for the lake next to their cabin.

Toghestiy: We’re not just fighting the pipeline; we’re fighting colonization. Colonization is rearing its ugly head because colonization is basically the industrialization of this planet. Governments are in place to facilitate the voracious industrial appetite for resources that don’t belong to them in the first place.

We have the Delgamuukw court case, and now we have the Tsilhqot’in case. Our people are bolstered by this. But you know, that’s not the only reason why we’re here. Our traditional laws dictate that our people should be doing exactly what we’re doing. And it’s not just our people; it’s all Indigenous people. I think a lot of First Nations people are getting that: they’re realizing that if they stay in their Indian reserves or urban centres and just exist in the system, nothing’s going to change. But if they get onto their ancestral lands, they’ll see exactly what’s happening to them and begin answering the call of their ancestors to protect them. That’s really inspiring for us.

What sort of tactics have the provincial and federal governments used in attempting to delegitimize your resistance or dissolve your resolve? How have they approached you or tried to deal with the Unist’ot’en Camp?

Freda: They haven’t. They’re saying that the only legitimate organization or legal entity they choose to recognize is the Band Council. To me, Band Councils have never had jurisdiction off the reserves and they don’t have any decision-making powers because the federal government makes all the policies that govern how the Indian Act Bands operate. But the federal government is trying to say they’re the only people they recognize because they decide for the reserves. They’re using that as an excuse to push forward even though Bands don’t have jurisdiction off the reserves. We proved it through Delgamuukw, through their highest Supreme Court: the hereditary chiefs and their members have a legitimate claim to the Wet’suwet’en territory.

What the government and these companies have done is extract resources from our territories and then give crumbs to the Bands to operate on. They’ve deliberately impoverished our peoples so that they can dangle a carrot in front of them. A lot of our people are struggling, and the leadership is thinking they’re doing good by trying to sign these deals – even though they’re for crumbs compared to the billions of dollars from a pipeline project. When the government decided they wanted these pipeline projects to go through, they said there was an “Indian problem” they needed to get rid of. Brian Mulroney and a bunch of other ex-Prime Ministers sat down and dreamed up this idea of putting money forward from the federal government to start what they called the First Nations Limited Partnership to try and get the Bands to sign on to Chevron’s Pacific Trails Pipeline, so that they could say they have Indigenous support.

The 2014 Supreme Court decision recognized the Tsilhqot’in Nation’s title to a large area of traditional territory in BC sets a precedent for Indigenous land rights. What needs to be done to establish those rights on the ground?

Toghestiy: Our people need to begin doing exactly what we’re doing. Our people need to begin moving out onto their territories, managing them the way their ancestors did. They need to design a protocol process that determines who they let into or prohibit from their territories. If we don’t do that, all will be lost forever. Nobody else will do it for our people.

Unfortunately, a lot of our people are in survival mode right now. We’re living life day-to-day, making sure that we can still find enough money to pay the rent, to put food on the table. As Freda explained, our people are put into a poverty situation and we’re still in survival mode. A large part of our diet, because we live in poverty, is processed foods, and that’s killing our people with diabetes, and with obesity. We need to be learning how to live off of our lands, learning how to harvest animals and plants and medicines the way our ancestors did so that we can begin to live healthy again.

Is that part of the reason you argue that instead of thinking about human “rights,” we need to start thinking about “responsibilities”?

Toghestiy: Absolutely. Rights contain the assumption that somebody has given you the ability to act out your responsibility. Rights create the illusion that somebody somewhere is going to say, “Okay. I’m going to give you this permission, my permission– and I hope you feel special about it – to act out your responsibilities.” That’s where the mistake lies, at the beginning of that thought process.

In order for us to exist as human beings on this planet, we have to take a really good look at our responsibilities as human beings. Rights are only there because we have this idea that somebody somewhere is going to give us those rights. That’s not how it works. We have a responsibility to treat each other well, to treat each other with respect.

If we start looking at responsibilities, maybe things will change. That’s what we did here with our permaculture garden. We went into a place that was clear-cut, where the soil was dead. It was our responsibility to the land to find a way to nurture that soil back to life. Now we have a vibrant permaculture garden, but that took a lot of work.

Everybody should stop thinking about trying to be a good citizen of the country that imposes itself on them and instead focus on becoming a good citizen of the planet. All of our ancestors were like that at one time.

What do you think that would mean for international solidarity with people with similar struggles for sovereignty, in places where there’s a higher level of impunity for government and industry who use force to get communities out of the way of development?

Toghestiy: We have the responsibility to make sure that those people are supported. Not just morally, but by getting out there and actually doing something tangible. A lot of people visit our website or the Victoria Forest Action Network website and find a way to support us. A lot of people come out and do stuff voluntarily for us: they spend a week, a month, a year. They want to contribute what they can because they know it’s making a difference. It’s a tangible difference, not an abstract idea.

When grassroots people want to get out and start looking after the land because they want to live up to the responsibilities their ancestors had, they should be supported in a real way. We need to set up an international network of people who are inspired to go and do something like that. We need to make sure that they’re protected, and that their children are protected, so that they can nurture that part of their soul that understands what responsibilities are, and live up to those responsibilities in a really good way.

People in Ecuador have also been fighting Chevron for decades. What are the links between their struggle and yours?

Toghestiy: Our sisters and brothers in Ecuador are suffering from the industrial decisions Chevron made in their backyards. Chevron had pipelines running through the Ecuadorian rainforest and oil wells that weren’t containing the oil properly. The government and corporations were corrupt and were hiding these spills. And then people started dying. The Ecuadorian court ruled that Chevron had to pay for the spills, and Chevron packed up and moved out.

Recently the Canadian Bar Association was attempting to intervene on behalf of Chevron, in the Supreme Court of Canada case where Chevron will be challenged for what they did in Ecuador. There was a huge uproar in Toronto, and the Bar Association decided to back down because of the public pressure. That’s what needs to happen here.

We’re fully aware that Chevron is trying to get a pipeline through our territories. They came right into our communities, we saw them and asked them questions. It was ludicrous, listening to them. I said point blank, “You guys are responsible for what happened in Ecuador. Now you’re trying to come into our backyards and do the same old thing and you expect us to ignore your history.” They tried to explain their way out of it and they couldn’t. The community just sat there and watched these guys fumble their words.

We have decided to join forces with people in Ecuador who are fighting Chevron. Over the next year we’re going to be doing a lot of things in conjunction to bolster our fight against Chevron, because they’re attempting to set up shop in other countries and totally dismiss the fact that the countries where they did the damage are trying to hold them accountable. What they’ve done is atrocious. They should be held responsible.

Given that history, can you describe how Chevron and other companies working to get support in your community, to get people to believe that they are capable of being the good neighbours they advertise themselves as?

Toghestiy: The corporations Chevron and Apache are working on the Pacific Trails Pipeline in our territory. They’ve actually taken quite a few people from our home community of Moricetown –community members, Band Councillors, and their families – and flown them out on a private jet to Calgary and Vancouver and to Fort St. John where the fracking fields are. They’ve entertained them in these places, given them massive honoraria, and convinced them that natural gas is safe. Industry and government are spending millions of dollars every year to fool the general public that fracked gas is the same as natural gas, when it’s very different.

In the more recent development, in June or July of 2014, the Moricetown Band was attempting to sign a deal with Chevron and Apache for the Pacific Trails Pipeline. The first draft of that deal was leaked and we got access to it. If they’d signed it, this is what they would have gotten away with: after five years of running the pipeline, Chevron and Apache would be able to sell it to a bitumen company – a tar sands company, like Enbridge and Kinder Morgan, like all these other fools who want to run this mock oil into international markets.

As soon as we saw that, our suspicions were confirmed. Now they say, “Well, the new deal we’re doing with the Band says we can never ever sell it as bitumen.” But what they leave out of that statement is “Unless the First Nations Limited Partnership agrees that it’s okay to do so.” The people in the First Nations Limited Partnership are very corrupt leaders of Indian Bands. If they decide they want to make a lot of money selling a fracking pipeline to a bitumen company, that’s what they’ll do. If they become members of this First Nations Limited Partnership group, they’ll have decision-making powers that don’t require them to consult with their own community members.

Do you think there’s a possibility that Moricetown Band will sign this agreement with Chevron and Apache?

Toghestiy: We almost got them the last time we had a meeting in Moricetown. The community was just outraged that the Band Council was even considering it. The chief councillor was going to get up and say that Moricetown Band will not consider signing a deal with that company, but one of the hereditary chiefs stopped him and said “no, sit down, don’t say that.” And they decided to see if they could negotiate another deal with that company. It’s bizarre: one of our hereditary chiefs stopped the elected chief from saying that they will not be signing any deals with pipeline companies. So, the corruption isn’t just amongst the elected chiefs, it’s beginning to be spread amongst the hereditary chiefs who are willing to get wined and dined by these guys. This one hereditary chief that stopped the elected chief gets hockey tickets to go watch the Canucks play in Vancouver. He gets season tickets in one of those private boxes. That’s his motivation to keep these pipeline companies really close. I’m not afraid to say that because it’s

the truth.

A lot of the struggles that we’re facing today are people not living up to their responsibilities – not just the chiefs, but the house members themselves. We need to find hereditary chiefs who understand that the territories need to be protected for future generations. Hereditary chiefs have a responsibility to look after the territories and determine when too many resources have been taken. That’s not happening. A lot of our hereditary chiefs today don’t even spend time out on their traditional territories. I don’t like saying that in public, especially in a public interview, but it’s the truth. It pains me to see our people struggling because we’ve allowed some hereditary chiefs to come into power who aren’t connected to the lands, who aren’t making sure that the future generations will benefit from the decisions they make today. Hereditary chiefs are supposed to be very selfless in their decision-making.

There is already a lot of opposition to the Energy East Tar sands pipeline that TransCanada plans to build from Alberta through Quebec, Ontario, and New Brunswick. Based on how your struggle has evolved, what guidance can you share for people resisting that pipeline?

Toghestiy: People need to realize that they’re not going to have the full support of their community right off the bat. That will grow over time. They need to have faith in the decisions that they’re going to be making to begin empowering the responsibilities that they have as grassroots members of their communities who want to see a better future for their people. If people are going to succeed at stopping the pipeline project, they’re going to have to come out and just do it. They can’t sit back and hope that their cousins or their best friends are going to finally step up and do something. They’re going to have to get out and do it themselves.

What do you think are the responsibilities of non-Indigenous allies in terms of support or solidarity work with Indigenous resistance?

Freda: I think it’s everybody’s responsibility to wake up and realize that if everything continues as it is, and if they continue to destroy the water via fracking, tar sands, mining, and even this foolish proposed pipeline, there won’t be any more fresh drinking water. And if you kill off the water, everything else goes with it. Vegetation won’t be possible; animals will be contaminated.

People need to go back to the basics, where – not only Indigenous people, I’m pretty sure wherever people came from – they took care of the water, and just took enough to sustain themselves and their families. It’s your responsibility to change the mentality that you have to have more of everything in order to feel like you’re alive. If you destroy this planet, you destroy yourself.

Toghestiy: This is going to be our sixth year of resistance against pipeline companies, but we’ve been resisting industry for a long time. That’s something our people should be doing all the time –not just Indigenous people but settlers as well. We need to protect the waters and set in motion a trajectory that will allow waters to be decontaminated, to reclaim areas, to work hard to allow them to return to their original state. Right now, things are going in the opposite direction: aquifers and watersheds are being destroyed because of industry and because of what government is allowing them to do.

I think all settlers need to become real, strong, tangible allies with the Indigenous resistance. There are a lot of Indigenous people who are suffering in their homelands right now because industry and government are destroying everything that they need to maintain their cultural identity. If people are aware of that and are actually sympathetic towards that, they need to really think about decolonizing. They need to decolonize their thinking and their decision-making, decolonize the way that they participate in society, and begin working with Indigenous people who need that help.

UPDATE:

In January 2015 the Moricetown Band Council voted to sign on to two pipeline agreements: TransCanada’s Coastal GasLink and (by joining the First Nations Limited Partnership) Chevron’s Pacific Trail. The Unist’ot’en Camp continues to grow, with the establishment of traplines on traditional Wet’suwet’en territory, and the building of a Healing Centre for Indigenous youth at the Camp. In May 2015, the Unist’ot’en Camp issued an urgent action alert when TransCanada began fieldwork on the Coastal GasLink pipeline in Wet’suwet’en territory. In late May, camp supporters peacefully evicted TransCanada workers found on the territory. TransCanada crews are making continual attempts to do survey work on the land, and have been evicted from the area several times by camp supporters. Chevron has received permits from the BC Oil and Gas Commission and has begun to clear a ‘right of way’ for the PTP pipeline. For some ideas on how to support the Unist’ot’en Camp’s resistance against Chevron and the PTP visit

www.unistotencamp.com. H