Transforming the World, Transforming Ourselves

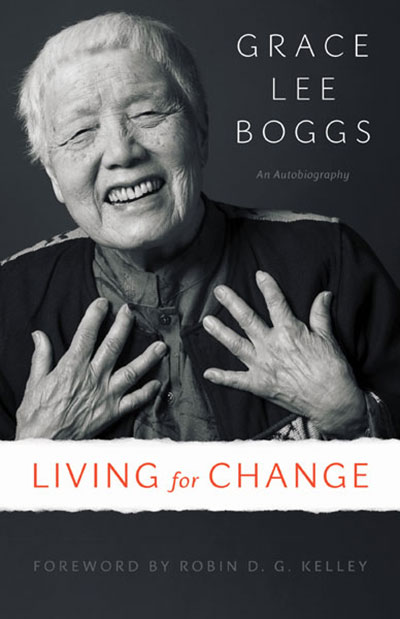

Living for Change: An Autobiography

Grace Lee Boggs

On October 5, 2015, Grace Lee Boggs passed away at the age of 100. A revolutionary, author, social activist, feminist, and philosopher, G.L. Boggs was a coordinating figure who played a key role in many political movements in the US since the 1940s. For this issue of Upping the Anti we wanted to commemorate the legacy of this American revolutionary with a review of her autobiography.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, and in the current atmosphere of global environmental crises, cascading rebellions, civil wars that cross borders, and the ripples of an ongoing economic slump, the campaign of Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders led “socialism” to become the most looked up word of 2015 on Merriam-Webster’s dictionary website. 1 This was a change from the 2007 top word, “w00t.” At such a crucial period, where an alternative to capitalism seems necessary, it is important for activists and organizers to begin thinking concretely about what alternatives may look like as well as how they will come about.

In her autobiography, Living for Change, G.L. Boggs forces us to grapple with these questions, challenging some of the taken-for-granted notions that remain in Left circles today. She demands that radicals contend with the conditions of life that are today “more complex than anything Marx could possibly have dreamed of.” (155). Change and adaptation are at the heart of her lessons.

As a text, Living for Change remains a tapestry of philosophic discussion and a rich history into the organizing and activism of an American Left from the 1940s to the 21st century. In this review, I will focus on key periods in G.L. Boggs’ life and key stages in her philosophic and political development through which her transformative politics emerge. The lessons she offers and her emphasis on communal self-transformation as a humanistic politics demonstrate why she remains a polarizing figure within a Left that oftentimes refuses introspection on the path to greater social change. For her, introspection is a shared growing and learning; a re-evaluating of our humanity.

The philosophers have only interpreted the world ... the point, however, is to change it

A first generation Chinese-American, G.L. Boggs began her intellectual journey as an undergraduate student, experiencing the social exclusions and alienation that would turn her “inwards,” forcing her to question pre-conceived notions about life and the world around her. These questions led her to graduate studies in philosophy where the seeds of her skepticism for timeless truths were sown. She continued her philosophical studies into graduate school, where her humanist approach to radical politics and organizing moved away from the deterministic politics of the socialist Left which limited human capacity to the sway of economic forces.

These first sections of G.L. Boggs’ autobiography, which reflect on her years undergoing philosophical study, can prove daunting and difficult to read, especially if readers are not previously acquainted with some of the concepts and theorists that she references. However, the underlying messages lay the ground work for insight into how she would think about political organization in the years to come. G.L. Boggs’ text also behaves as a rich catalogue of primary and secondary source references, deliberately stated so that future readers may peruse them for more clarification as they undergo their own journeys and growth as students, organizers, and activists.

Feeling informed and empowered to move into a world where she could practically apply her skills and where “doing had priority over knowing,” G.L. Boggs began to work with the South Side Tenants Organization in Chicago. The organization was involved in a struggle against rat-infested housing—a reality close to her experience living in a shared basement apartment with only a coal furnace. In this organization she was put in contact for the first time with the Workers Party—a small Trotskyist group—and with residents from the Black community. In these experiences G.L. Boggs testifies how she began to learn about organizing protests and demonstrations, and more about the realities of segregation and discrimination in people’s lives—on a scale much different than what was experienced by Asian-Americans.

In these chapters on her early experiences of organizing, G.L. Boggs describes how she began to perceive socialist organizations as “on their way out” just as “something new was beginning.” The groups that G.L. Boggs describes were internally divisive, mechanistic in their analysis of capitalism, and used “the writings of Marx, Lenin and Trotsky in much the same way that Christians use the Bible” (51). Developing her own more nuanced approach to the work of Marx allowed G.L. Boggs, along with C.L.R. James and Raya Dunayevskaya, to draw out an alternative interpretation of his work, one which they read in relation to that of Hegel. This reading stressed the need for liberating the self-activity and self-determination of the workers from the capitalist mode of production. In contrast to their comrades in the Workers Party, the members of the Johnson-Forest Tendency (named after the pseudonym’s of C.L.R. James and Raya Dunayevskaya) resisted the economic determinism that placed workers as mere appendages in the development of capitalism, and instead stressed the humanistic aspects of Marx’s work that focused on humankind’s alienation or estrangement from their “human essence.” For them, Marx’s earlier writings were important in that they reinforced the view that “the essence of socialist revolution is the expansion of the natural and acquired powers of human beings, not the naturalization of property” (102). 2

In reference to what was called “The Negro Question” at the time, G.L. Boggs described the predominantly white socialist radicals as being invested in leadership by a mainly “white working class.” Instead, the Johnsonites took the position that revolutionists should encourage and support independent Black struggles, and instead of trying to incorporate or control this struggle, “revolutionists should trust that the momentum of the struggle will bring out the hatred of bourgeois society that is latent in the black experience” (56). 3 Through her own organizing and political experience, G.L. Boggs came to see the role of Black liberation struggles in positioning Black workers as the vanguard of the struggle against capitalism.

In our current times, there are numerous lessons to be taken from these reflections by G.L. Boggs, as movements such as Black Lives Matter, Idle No More, and the campaigns against deportations and borders are emerging as powerful sites of resistance against the capitalist state. Those on the Left who are content with criticizing these movements unless and until they adopt a particular vocabulary of class politics forget to realize, as did many socialists from the past, the existing anti-capitalist character and potential of these movements.

These questions have been perhaps magnified in the atmosphere of a Trump presidency, where in an attempt to answer the questions “what went wrong?” and “how did this happen?” many on the Left have resorted to dismissing what they deem as mere “identity politics,” which in their minds has done more to fracture the working class than to unite it. At such a time, those who want to think seriously about the place and role of anti-oppression and identity politics in revolutionary movements need to be able to contend with these charges emerging within the Left, which have not changed much since G.L. Boggs’ organizing days. It is in her life story that we find companionship and direction.

Moving to Detroit

In the early 1950s, G.L. Boggs moved to Detroit to contribute to the workers’ journal Correspondence. There, she found herself further embedded in the Black struggle and continued the development of her reconsiderations of traditional Marxist concepts. G.L. Boggs’ discussion of the journal Correspondence highlights the ways in which a radical print journal was able to function as an organic publication that avoided speaking to or for the masses, and instead spoke with them. Correspondence included a column titled “workers journal” and six columns dedicated to “readers views” which were intended to reflect what workers were saying “in the plant.” As well, the editorial committee included workers like Johnny Zupan from the Ford plant and Jimmy Boggs, G.L. Bogg’s partner, whose approach to community and organizing would signal another stage of change and development in G.L. Boggs’ thinking and self.

Jimmy and G.L. Boggs would be the last of the remaining Johnsonites to continue organizing in Detroit after Raya Dunayevskaya had split from the organization and C.L.R. James was forced to leave the country by US authorities. Eventually, C.L.R. James too would part ways following disagreements with G.L. and Jimmy Boggs over their further criticisms of traditional Marxist concepts, which are further explored in Jimmy Boggs’ book The American Revolution. For Jimmy, Marx was developing his ideas in a particular time and history and that if they were to remain relevant to today, they would have to be radically altered in pace with the rapid changes taking place in American industry and society. What was needed was not a reaffirmation of, or education in, Marxism—which was C.L.R. James’ suggestion following a reading of The American Revolution—but a “serious study on the development of American capitalism” (107).

For G.L. Boggs, Jimmy’s commitment to adaptability and his respectful but critical approach to Marx’s ideas demonstrated the differences between an “organic intellectual” and a “revolutionary intellectual.” C.L.R. James, who remained isolated and exiled from the struggles playing out on the ground, and whose ideas came mostly from books, represented for her the revolutionary intellectual whose thinking was not rooted in the ongoing struggles and reality of the people. Echoing some of the characteristics of the “organic intellectual” as described by Marxist revolutionary and theorist Antonio Gramsci in his Prison Notebooks, G.L. Boggs describes the organic intellectual through figures such as Jimmy Boggs and Malcolm X, who she argues were constantly changing and developing their thinking as was required. Malcolm X, she contends, reflected the qualities of a real revolutionary, always transforming himself with humility, and always expanding his humanity.

Through their example, and following her break with C.L.R. James, G.L. Boggs states that her ideas began to “come from reality and not just books.” She began to entrench herself in the city she lived in and molded her activism and organizing further within the community. This commitment to transformative practice and organizing, as well as a focus on the place and importance of expanding one’s humanity and self, would influence her and Jimmy’s further reflections on rebellion and revolution, and of the place and role of the Black struggle at a new stage in history.

Rebellion vs. Revolution

In her discussions of societal change, G.L. Boggs draws from Hegel the necessity of transformation in terms of “dialectical thinking” and of “dialectical humanism.” Though an abstract term, “dialectic,” as G.L. Boggs uses it, tries to grasp an element of motion, change, and transformation, all happening in an interconnected way. To think dialectically means, first of all, to be able to “think,” an activity surprisingly denied by some on the Left who relegate every human thought as something determined and directed by an economic base or the economic organization of society. For G.L. Boggs, however, the creative potential of human beings must be appreciated, which allows us to engage in a critical way, not necessarily above and beyond, but in relation to and immersed within the social environment. Only as such can we modify our preconceived notions and adapt them.

Learning from the rebellions they saw unfold in Harlem or the 1967 uprising in Detroit, G.L. and Jimmy Boggs insisted on the need for people to transform themselves in order to transform the world: “those who need to make a revolution also need to transform themselves into more socially responsible, more self-critical human beings.” Drawing from revolutionaries such as Mao Zedong, Ho Chi Minh and Amilcar Cabral, they argued for a “build as you fight” strategy for revolution that went beyond Marx and Lenin. Instead, they insisted on fighting on two fronts: the mobilization of the masses against an external enemy, and the creation of structures and institutions for the transformation of the masses into new beings. G.L. and Jimmy Boggs described this latter form of change as “revolution,” whereas “rebellion” was simply a stage in the development of revolution—a breaking of the threads that held the system together.

This valuation of transformation both on a structural level, as well as on a human and personal level is one of the major issues that some organizers on the Left have had with G.L. Boggs. It was even, she admits, a reason for the split with C.L.R. James in 1962. G.L. and Jimmy Boggs were insistent that any movement, if it were to succeed, would have to be moved by new, revolutionary subjects. Though G.L. Boggs does not lapse into a new-age focus on individual transformation, she does force us to grapple with the possibility of self-transformation under the existing alienating conditions, rather than promoting a passive waiting for the abolition of private property before we re-emerge as fuller human beings. Such a balance is difficult, and the question of how to engage with both without minimizing the importance of the other remains inconclusive in her book—perhaps intentionally.

Not waiting for change

While the shape or form of future movements and societies is still unknown, what remains clear today is that change is needed. In Living for Change, through her own life’s story, G.L. Boggs provides us with a method for answering these questions without offering definitive solutions or secret formulas. Through her method of critique and emphasis on transformation, her own conclusions about the necessary forms of struggle, and the part and place of a particular movement or even the character of revolution, are bound to become contradictory.

For activists and organizers today, G.L. Boggs’ autobiography—an inspiring account of a life of revolution and transformation—reminds us that so long as the conditions in which we find ourselves continue to change, we must adapt our tactics and develop our strategies. Though it is true that socialism is making a “comeback,” for today’s serious activists intending to fight against oppression, it is important that we do not repeat the mistakes of the past—that our politics become reflexive and adaptable rather than static or a salute to bygone days and strategies of old. Through her life story, G.L. Boggs not only inspires us to do so, but compels us to.