This is Where the Drug War Ends

Reflections from the Frontlines in Moss Park, Toronto

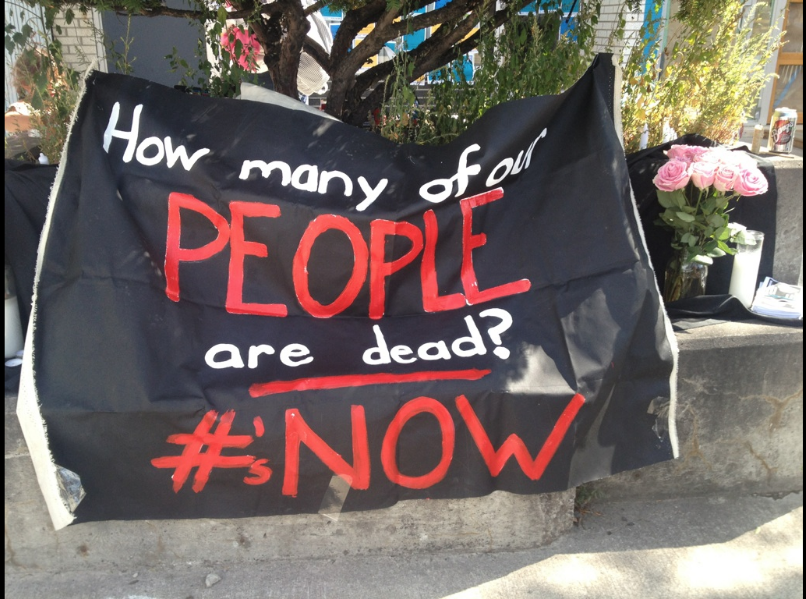

The Toronto Overdose Prevention Site (tops) opened in Moss Park in August 2017 to address the escalating opioid overdose crisis. The Public Health Agency of Canada predicted that at least 4,000 people across the country could die of an opioid overdose in 2017. There were 1,053 opioid related deaths in Ontario between January and October of 2017, representing a 52 percent increase from the previous year. 1 The death rate continues to be higher than any other infectious epidemic in the country’s recent history, and shows no sign of slowing down.

Following months of government inaction in the face of the escalating overdose crisis and bureaucratic delays in releasing funds to the three planned Supervised Injection Sites (sis) in Toronto, a group of harm reduction workers and drug users from the Toronto Harm Reduction Alliance (thra) 2 took action. thra decided to open an unsanctioned pop-up site in Moss Park—the first of its kind in Ontario. They set up makeshift tents for folks to use drugs in a safer environment, with medical and harm reduction volunteers on hand to intervene in case of overdose. The opening of the tops created pressure on the city of Toronto to speed up the process of opening a temporary sis at Toronto Public Health, The Works, in late August 2017, which was later replaced with the previously planned permanent site. 3 tops organizers also worked closely with harm reduction workers and advocates in Ottawa, which led to the opening of Overdose Prevention Ottawa, the second unsanctioned overdose prevention site in Ontario. 4 The existence of the Ottawa and Toronto sites also put pressure on the provincial government. After five months of operation, the Ontario government started accepting applications for the opening of Overdose Prevention Sites (ops) all over Ontario. 5

As of March 2018, the tops had over 5,000 people use the service for injections alone and the volunteer-run group has reversed over 185 overdoses. 6 The site continues to run seven days a week, operated entirely by volunteers. Nanky Rai and Gunjan Chopra spoke with two organizers, Matt and Fiona, a month and a half into the project.

Since this interview was conducted, another overdose prevention site has opened in Toronto’s west end neighbourhood, Parkdale. With the recent election of Doug Ford as premier, the future of all harm reduction sites in Ontario is in jeopardy.

Fiona White is an outreach worker with Queen West Community Health Centre (qwchc) and will soon be working at one of the three sis in the city. She is also a volunteer at the tops in Moss Park and a public educator on harm reduction, drug use, and homelessness.

Matt Johnson is a long time injection drug user and harm reduction worker. He is one of the organizers of the tops in Moss Park and continues to fight for an end to criminalization of people who use drugs.

What are your organizing principles and what does the structure look like for the pop-up overdose prevention site in Moss Park?

Matt: One of our principles is “nothing about us without us.” It was key that drug users be part of the ops from its inception to our last day. I’m a long time injection heroin user and an organizer. We made sure to reach out to and involve people who are drug users.

Fiona: And just being very low barrier. We are right in the park. You don’t have to sign in, you don’t have to check in, you don’t have to give your name if you don’t want to, which is really important as far as us having clients and making them feel safe. A lot of them really would not feel comfortable using inside of a shelter or a hospital or maybe even an indoor safe injection site. It’s part of meeting people where they’re at.

Matt: Also, becoming involved is low barrier. There’s a guy who was just in the park and showed up on the first day to use the service and became a volunteer who comes multiple times a week. After that first weekend we wanted to decentralize leadership, so we got a larger leadership group together. We’re really strategic about tapping people with a lot of experience and knowledge and giving people a lot of autonomy. We have tried really hard to get not just buy-in from the community, but help from the community. There are a lot of people from the community who are volunteering in some capacity. We have worked hard to get feedback, and make sure that people see that their feedback is put into practice. We have to build consensus. People have to agree with the policies or else it’s not going to happen.

Fiona: What a huge difference it makes when something is peer-led versus top-down! Somebody came into the tent and started sharing these great ideas for community consultations and the first thing I did was grab the shift leader and connect them. The shift leader responded immediately, took down the person’s contact information, and invited the person to join us. That’s bottom-up, not top-down.

Matt: Whoever is using the service owns that service. We really want community ownership, so if we have to turn things upside down to make that person feel comfortable, we’ll do it if that’s what that person needs. That’s what real harm reduction is always about. It’s about building community capacity, and supporting people who are drug users to take more ownership over service provision and planning. That’s how I got introduced to harm reduction, by people who really got it, and that’s why I am where I am. I got introduced to it as a client, and then as a peer worker. When I couldn’t go any further as a peer worker, I had people who supported me to go to school so I could become a program coordinator. If I’d gone somewhere else, they would never have seen it as being possible for me to go to school at all, let alone take over the job. You know, Barb Panter was one of my mentors, and I have the job she had. She really saw me being able to get there. How many people look at a heroin user who’s on and off the streets and say, “You can do my job, and get a salary”? That’s just a very different way of looking at the world. It’s a different way of looking at what’s often labelled as weakness. We aren’t just about opening one site where people can use; we’re looking at transformational change.

What inspired you to do this, and are there particular ideas or examples you had in mind of different forms of direct action that supported this work?

Fiona: I don’t know if “inspire” is the right word. It’s more that we were scared into it. It’s a really terrifying place to be, to be an opioid user in Canada right now. It’s absolutely terrifying to have friends who are users as well. Less “inspired,” more “what else can we do?,” because we can’t change the laws. From where we’re standing we can’t decriminalize it. Harm reduction looks at what we can do right here, right now, and that is the simplest most obvious answer, as far as what we can do.

Matt: There are many safe consumption services throughout the world. As harm reduction workers, we are really knowledgeable about the range of safe consumption services that exist in other countries. 7 So we were able to pick a model based on some of those, and pick and choose from different ones. We were inspired by the sites in Vancouver. They also started as unsanctioned pop-ups and then became funded. So there is a precedent for us to open, and say, “Other governments have come forward and funded, so if you don’t it’s not really about us, this is about you not being willing to tackle the problem properly.”

You have this sign up in the tent that reads, “You have permission to heal yourself.” How does the ops and harm reduction in general foster healing?

Fiona: You can look at it on the very basic level of somebody coming in and feeling sick because they need to use. When they use, they get better. But it’s more than just that—society has such a “don’t do drugs” perspective, and I think a lot of people use drugs to feel better, whether it’s to heal themselves emotionally or physically. We wanted a space that said, “You have permission to heal yourself” even though the rest of society may say these are illegal or you’re illegal, this space is not that.

Matt: It’s powerful when people see and hear that they have the right to safety. I think a lot of people would not really understand that. For users, especially street-involved or homeless users, you basically never have the right to be safe. To put forward this place where people can be safe for the first time in a while—the healing potential of that is enormous. Even if it’s just for a moment. There’s also the healing that takes place when you build a greater sense of community and greater community bonds with people. We have people who are volunteering with us who started off just using the tent and then really enjoyed it and wanted to help out. And the number of people doing that is increasing. We have people who are volunteering for us who don’t even identify as volunteers. They’re people who knew about us so they went out and grabbed a bunch of people that they care about and brought them to the tent to make sure that they use the tent. That’s doing volunteer work for us and that’s certainly healing on a community level. There’s amazing healing power in being able to give back to your community, being able to help care for your community, and doing the kind of work that’s done within your own community. It’s transformative.

Now that it has been over a month and a half of organizing, what would you want folks in other cities to know? What have you learned?

Matt: I would want other people to know that it’s very doable. We have people who come to the ops informing us how they do this for their friends all the time. We have a volunteer who gets extra naloxone kits because when we’re closed, he tours the neighbourhood finding people who are overdosing and he naloxones them back to life.

Fiona: The site is just a coming together of all these people who are doing it for their friends and their family members. It’s people who were doing it anyways and rather than doing it separately, now we’re doing it together. That makes it easier and it really does take the weight off. It makes it bigger than you. There’s something bigger happening. There’s a movement. So I’d like to remind people they’re doing it anyways, just put the pieces together.

Matt: You can get a lot of energy being part of some kind of movement rather than doing it alone.

What are some of the supportive and also challenging ways that people are responding to your organizing at the local, provincial, and federal level?

Matt: I don’t think the federal government knows we exist. We’re, at best, a pain for the provincial government. We’ve been pushing them on a lot of different fronts. We’ve been saying that they should be funding us. They’ve done absolutely nothing to show that they care about drug users at all. On the local level, it’s been really varied. Fortunately it’s been more positive than negative. We have a few city councillors who have been working with us. In Ottawa, they’ve had a really different experience. We’ve been in close contact with our fellow organizers there who are doing a similar thing. And there are a few of them there who are receiving death threats.

Fiona: People in the neighbourhood seem to really understand why we’re there and they do their best to be supportive. They’ve donated to our GoFundMe campaign 8 or they bring water or juice. We had some trouble with ems not being 100 percent supportive. I’m not going to say it’s been a challenge because we don’t really deal with them that often. I think they feel challenged by us.

Matt: City-wide it’s been mostly positive. There have been a couple of folks who have come and said crappy things to us, and that’s really difficult. It’s really hurtful. People are often too cowardly to say this to our faces, but occasionally there are people who have come to the site and said, “Just let them all die.” When people say that, it’s like they’re talking about me, and they’re talking about the people who I love and care about the most in the world. That’s hard to hear that there are people that wish death upon me and my community. And that’s a strong minority opinion. And it’s not that out there. People feel like they not only have the right to say that, but that nobody should even be trying to make them feel bad for saying it. It would be nice to feel like we’d made a bit more progress when it comes to recognizing the humanity of drug users.

In some ways, there have been shifts in perspective from the mainstream media. For example, now they use more humanizing language like “people who use drugs” in contrast to the language describing Black users and the “crack baby” image. How do you think that has changed over time and how does that influence your work now?

Matt: The way the media talks about it has drastically shifted. You see this with politicians too. We’re hearing statements like “this affects everybody,” “this affects all communities,” and “it’s not just ‘some people’ anymore, everybody’s dying from this.” Actually that’s not true, it’s still predominantly the same people who are dying. It’s the same people using drugs daily or non-recreationally. There’s this myth that suddenly it has hit white upper middle-class kids from the suburbs. The difference is that opioid overdoses are more often fatal than other types of drug use. So when cocaine was popular, cocaine users would not likely die from cocaine overdoses, they would have died from living in poverty for long periods of time. So the real difference is that opioid overdoses are more likely to be fatal, so people who are using recreationally are at a higher risk of a 911 overdose or a fatal overdose. And some people overdose when they’re early into their use rather than after they’ve been doing it for a long time.

Fiona: I’ve been seeing a lot less demonization of drug users and a lot more of “check your facts,” especially online. Anytime anybody says something, you can pick up your phone and see whether or not that’s true. I think there’s definitely a positive shift with the younger generation.

Matt: It’s true, they don’t want to demonize users. I think it’s also that in the 1980s, alongside the “crack baby” scare, the gay aids model became pretty thoroughly entrenched. There’s still a belief that being hiv positive was people’s fault. Nowadays, however, the disease addiction model is really prevalent. When I see the comments sections on social media there’s always someone talking about how drug use is a disease and that people can’t just stop.

At the same time, the neoliberal media says, “Yeah it’s a disease, it’s not quite their fault, but the fentanyl dealers, they’re the ones we should demonize, and they should be charged with manslaughter when they sell fentanyl.” The users they like to talk about are “nice white Timmy from the suburbs.” While the dealers they like to talk about are young men of colour from the inner city. And Timmy, who’s a white drug user, it’s not his fault, he got hooked by a doctor, he’s just trying to get his next fix. If he does something bad, it’s like, “Oh poor him he’s just trying to get by.” Whereas the guy who’s selling it, it’s like, “Oh he’s evil, he’s a predator. He’s not trying to get by from day to day, he’s not dealing with poverty, he’s a bad person.”

How do you think the organizing you’re doing right now, both the service provision and also the movement building that’s happening as a result of the ops, is building solidarity across different movements, especially around anti-capitalism, decolonization, and racial justice?

Matt: There has always been a strong connection, at least locally, with anti-capitalist movements. Our hopes and goals align with organizations like the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (ocap) who have done a lot around drug use. A lot of us harm reduction activists are also anti-capitalists and involved in these other movements. Our harm reduction beliefs and activism aligns with what anti-capitalists want. We want to go beyond the decriminalization of drugs, we would also like to see the decriminalization of poor people.

Fiona: It’s great that we have an overdose prevention site, but what about everything else? What about getting safe housing, a safe place for people after their high? All these other services are a part of anti-capitalist movements. We’re connected with Indigenous individuals and with people of colour but I wish we were more connected with groups that discuss the racialization of drug use and drug users and how people of colour are more targeted by police when it comes to drug crimes, and by stigma.

Matt: I’ve been thinking about this lately, that harm reduction isn’t white. The people who get to talk about harm reduction are. If you look at the people who are using the tent, it’s a mixed group of people. But then when you look at who gets hired at The Works, nurses are white and people with a master’s degree in social work are white. This is a problem that happens again and again: a group of drug users push for change, funding comes through, and then a bunch of white middle-class nurses end up getting hired. I’m a white man and I get it too. We just did a speech at the Board of Health and one of the city councillors made a comment about me that put me in a position of speaking on behalf of a group. I’m not saying anything different than what everybody else is saying, you’re just picking me out because I use certain language, I am a white male with a home and a good job. It’s easy for me to get up there and identify as being a drug user. There are other people who spoke but I’m the one who’s more likely to be praised based on the privilege that I have. Harm reduction gets co-opted by white people with money, but it isn’t actually a white movement when drug users are leading it.

With regards to movements for decolonization, a lot of people have not been supportive of harm reduction given that substances and substance use have been a tool of colonization. People have been concerned about harm reduction just being another tool of colonization as a way to keep people on drugs and therefore unable to organize. I’ve seen that shifting for a lot of people and a lot of different organizations. We’ve partnered with different Indigenous organizations 9 and individuals to make sure that other voices are heard. We’re not interested in representing a small group of people. We want to make sure that we’re not focusing only on settler issues. And also just recognizing that there are some needs and services that we as settlers can’t provide, so we need to work together to make sure that there’s more of a holistic approach. Fiona wrote the sign, “You have the permission to heal,” and healing is going to look different for different communities. We can’t offer everything that everybody needs to heal at one site, but we are at least knowledgeable enough to connect people to others or point people in the right direction. We have more to do to build more connections between movements and organizations and more work to recognize that we are all striving towards similar goals, and the more we can work together the stronger we are. It gets difficult because the powers-that-be do not want us to organize collectively, so they make efforts to try to sow discord and suspicion. And they’ll keep doing that. It’s ongoing work that we need to do.

If you’re somebody from outside of the harm reduction community you need to educate yourself to really challenge the notion that people who use drugs are your enemies. In any movement or community there’s going to be people who are drug users, and who deserve to be part of those movements just as much as everybody else. Also, we all use drugs. Some of us use the ones that happen to be illegal. Most harm reduction organizations are desperate for allies. We’re often pretty alone.

Can you talk about the difference between decriminalization and legalization?

Fiona: Decriminalization means removing the laws making something illegal. So under a system of decriminalization, the people trading or moving the drugs would remain the same. Legalization allows for taxation and for the government to control the substances if they so choose. Then there’s corporatization. On one hand, I want access to safe drugs, but on the other hand I don’t want McDonald’s selling me my drugs. It’s this interesting line where the black market becomes a grey market in the decriminalization system. Selling drugs is also a low barrier job opportunity, and a lot of people are supported by that. If you legalize, you take away their jobs.

Matt: The issue is that there are a lot of different models for decriminalization, and it’s really easy to get wrong. You can look at decriminalization of sex work, that’s a good example. There’s a Scandinavian model of decriminalization of sex work that’s incredibly oppressive and doesn’t help. There’s decriminalization where you decriminalize users who are using small amounts but heavily criminalize drug dealers. At the other end, there’s decriminalization where you’ve done everything except take the laws off the books. Then there’s mixed decriminalization, like Portugal, where the laws are still on the books, so if you’re doing things that are considered societally disruptive they can haul you in on this crime you committed as a way to gain leverage and control over you. But McDonald’s can’t start selling a crack burger.

I personally support the legalization of all substances by prescription, and the decriminalization of all substances including manufacturing, selling, and possession, down to the point where it’s on the books just to stop corporatization. I’m not super stoked about the idea of the government regulating my drugs; I’d much rather have the government regulate my drugs than a corporation regulate my drugs. That way, there can be a grey market. I shouldn’t have to rely on the government for all medication that I want to take. It’s my body and I should be able to put what I want into it. So if I can get a doctor to prescribe it for me, great. If I want to order it over the internet, great. That’s the way that we deal with most other things. We have fda laws about what food is allowed to be in Canada, but I can order whatever the hell I want, I can order unpasteurized cheese from France for example.

There are two ways that I see decriminalization happening. One is that things get so bad that you have no choice but to try something new. Or it’s chipped away over time. We could have police agencies in Canada say, “We won’t arrest or prosecute drug crimes anymore,” which I think would be a good first step.

Fiona: I think one of the things we need to start talking about is how much money our pop-up alone is saving the city of Toronto, ems, and hospitals.

Matt: The thing is that, if it came down to the money issue, we would have decriminalization. That’s the problem, it doesn’t matter how much money we save. Because there’s so much more money being generated by the drug war for the people who are profiting from it. The money that we’re saving is for taxpayers in general, but not for the right people. I think that the leaders of legalization and decriminalization are going to be countries that have less wealth, and don’t have the power that countries like the us and Canada and most countries in Western Europe have. My belief is that they’re going to push it forward in big leaps and bounds, and then it’ll be a slow chiseling away for the places that often call themselves global leaders. And there’ll be the holdouts. The us is probably going to be a holdout for a long time.

What would it take to end the overdose crisis in Toronto or in Canada?

Matt: To address the overdose crisis, you need to end the war on drugs. That’s the only way to do it. Otherwise it’s all band-aid solutions. I mean what we’re doing in Moss Park is a band-aid solution. We can’t even address all of the overdoses in that area. Two people died when we were closed. Without an end to the drug war, without an end to criminalization, everything is just a band-aid. Now when you have the un calling for decriminalization, it’s going to happen. But at this stage, it’s unclear if it will happen swiftly like it did in Portugal or slowly over decades. If we addressed the issue of capitalism, it would happen so much faster. Oil profits run the world, but so does cocaine money and other drug money. Those large banks that are making billions laundering drug profits do not want an end to the drug war. And people like Donald Trump, who make a lot of money from the current economic system, do not want an end to the drug war. We tend to focus on our individual governments for change but the drug war is tied to the global economic system of wealthy nations.

Fiona: Give us a safe supply of drugs. We need to decriminalize, we need to have safe sources for drugs. It’s like the chicken or the egg problem. Does it start with an attitude shift in the public and the politicians change? Or does it start with the politicians and activists speaking out and then the public changes? What causes any kind of paradigm shift? I would say it’s education and spreading facts. Harm reduction is logic based. Harm reduction is common sense. We’ve tried putting people away in jail for selling drugs. We’ve tried putting people in rehab for using drugs. Has that changed anything? No. So let’s try to look at this from a different perspective. •

Notes

7 Portugal is an example of successful drug policy: Susana Ferreira, “Portugal’s Radical Drug Policy is Working, Why Hasn’t the World Copied It?” The Guardian, December 5, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2017/dec/05/portugals-radical-drugs-policy-is-working-why-hasnt-the-world-copied-it.