Why Don’t We All Rise Up?

Thinking About Resistance with Nangwaya and Truscello

Why aren’t people outraged?” is not a question I often ask myself—it seems that outrage is everywhere, overheard in conversations and witnessed in public life. On the other hand, “Where is the collective expression of this outrage? Where is the collective struggle?” are questions that perpetually niggle at my mind. Living on the edges of the continent, in an isolated rocky province with a near unbroken legacy of poverty, a horrifying colonial history and present, and currently in the midst of yet another economic crisis, I often ask where the collective struggle is to fight the existing state of affairs? In times such as these, as dire as they often seem, concerted collective action is notable here for its absence. Why is there no unrest? Why are “the poor” (the vast majority of the province’s population) not “rising up?” And, even if they are, as individuals, what can—and must—organizers do to translate general discontent and anger into sustained collective action? As an often lonely organizer on these shores, I picked up Ajamu Nangwaya and Michael Truscello’s edited collection, Why Don’t the Poor Rise Up? I wanted to see if and how I could apply its myriad lessons to my own struggle in Newfoundland and Labrador (NL)—an isolated province with a small population bearing little politically in common with economic centres like Toronto or Vancouver.

The book’s divisions into two distinct sections—The Global North and The Global South—were the first surprise, in that several of the stories told in the category of the Global South addressed questions and concerns of organizing that seemed more relevant to my experience of organizing on the margins of the Canadian state. But the book, and its 17 chapters plus foreword and introduction, were full of such surprises of the small yet cataclysmic kind. Covering Indigenous struggle, race and policing, Black labour, the alt-right, and anti-poverty movements (in the North section) and anti-poverty, environmental, policing, and healing struggles throughout the Caribbean, Mexico, Kenya, Sudan, and South Africa (in the South section), the book is wide ranging and offers new stories if not always new lessons for just about anyone.

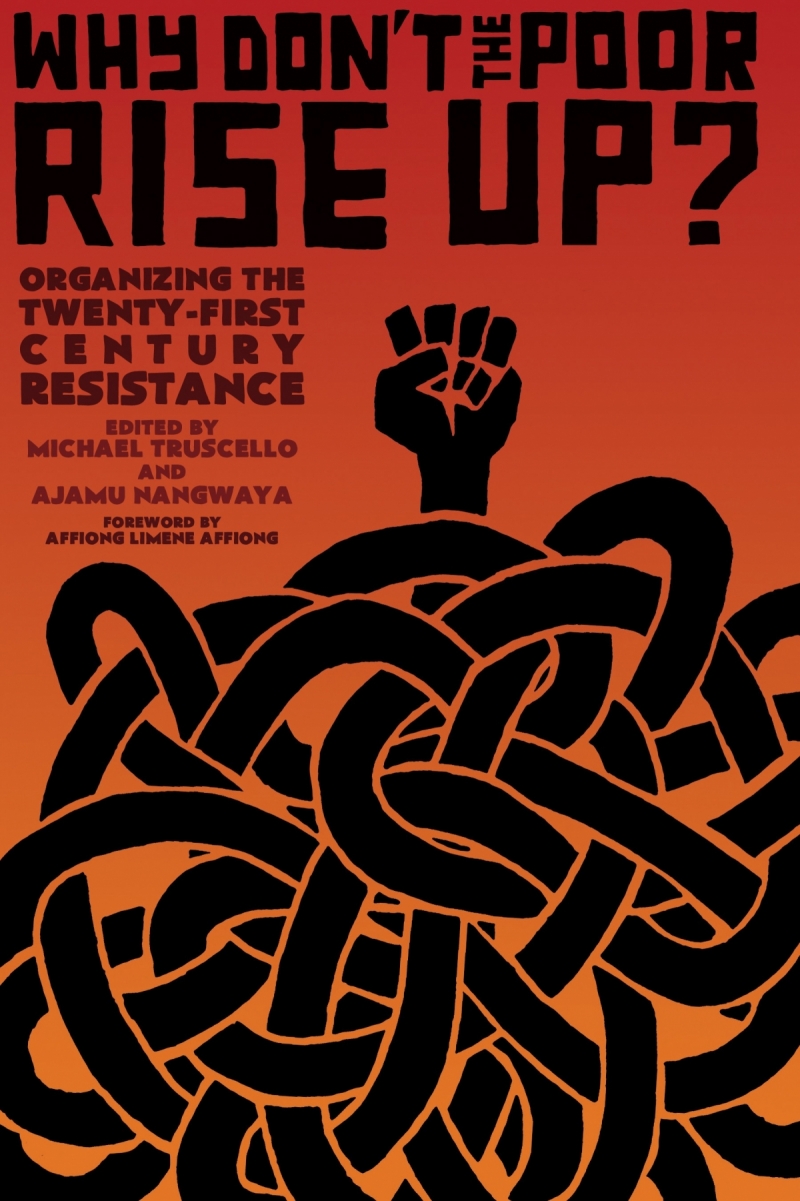

The title of Nangwaya and Truscello’s collection comes from a 2015 New York Times op-ed of the same name by Thomas Edsall, a journalist and Columbia University professor. While several of Edsall’s assertions are not wrong—neoliberalism has brought greater levels of individualism, household incomes for working class people have bottomed out while wealthy households’ incomes have skyrocketed—it is the fundamental premise of the assertion, that the poor are not in fact engaged continually in projects of resistance and uprising, that the editors of this collection dispute. Nangwaya and Truscello argue that the framing of Edsall’s question itself asserts a liberal narrative that is fundamentally incorrect and incomplete. And this argument is supported by foreword contributor Affiong Limene Affiong, who asks, “Is it true that the poor do not rise up? Or do we simply not recognise their resistance and rebellions?” (1). Alex Khasnabish addresses this question in his chapter on the radical imagination. He reminds us that asking why they don’t rise up is part of an “endless deferral of responsibility on the part of the socially privileged speaker” (120) and does not implicate oneself in the process of collective liberation. Instead, Khasnabish and several other authors insist we must work to collectively understand what is possible through struggle and what propels and animates movements of resistance. In order to bring these rebellions into recognizable light, Nangwaya and Truscello offer a set of global perspectives “on the ways in which the poor are defined, the forms in which they resist, and the obstacles to mass insurrection” (22). In the end, the collected chapters provide evidence that in fact we do rise up, we have risen up, and we will again rise up, and in so doing charts our collective missteps so that we can, as Samuel Beckett urged, fail again; fail better.

Not wanting to endlessly defer responsibility for resistance, reading this collection made me reflect upon my own place in the world and in struggle. I currently live in NL, a province recently revealed to have the highest levels of income inequality in Atlantic Canada. It is a place geographically removed from the rest of Canada and that physical distance reflects itself in a removed mindset: its rugged landscape populated by those proud of their ability to withstand isolation, barrenness, and an often unrelenting wind. It is also far removed historically and culturally from urban centres in the rest of Canada, only joining the country 69 years ago. This distance makes it a doubly difficult place to organize as a radical, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, settler interested in decolonization. Those who organise in NL perpetually lament the inability to bring more people together due to a lack of familiarity with the tactics of social movements and a lack of history of resistance (outside of the fishery), but also because of the distance felt from centres of political resistance, and the difficulty in connecting what is happening elsewhere to what is (or isn’t!) happening here.

NL is a place with histories of struggle. However, these struggles were often centred on individual or community-wide ways to cope, subsist, and survive rather than giving voice to collective expressions of outrage. Isolated into small coastal communities and at the mercy of merchants for generations, 19th century fishery workers engaged in spontaneous acts of rebellion but little organized resistance. Collective organizing came in the seal fishery in the 19th and 20th centuries—then-socialist Joey Smallwood famously walked the length of the island along the railway tracks organizing rail workers in the 1920s. Certainly organized collective struggle has existed in NL, but it also has a long history of bitter betrayal—Smallwood’s turn on unions in the 1960s, for example—and genocide—the Beothuk people, upon whose land the colony squats, were systematically murdered over the course of colonial settlement. Newfoundland and, even more so, Labrador are peripheral zones of extraction whose Indigenious and settler populations have been contained or put to use in the concentration of wealth central to processes of colonization and capitalist expansion. Organizing for resistance, rebellion, or even revolution at the edge of empire—in the peripheral zones of extraction—has long been a challenge. It is even more so when you live on a remote island with few experienced organiziners or long lineages of radical movements and ideas to draw from. From this chilly rock, amidst so much inequality, so much blatant thievery, racism, and resource extraction it may be easy to sense people’s outrage, but difficult to understand why there isn’t more unrest, more revolt, more “rising up.” Why here—and of course, elsewhere—is capitalism viewed as the only permissible game in town?

Ajamu Nangwaya and Michael Truscello’s edited collection emerged at the exact moment I was asking myself and others what we can do to advance struggles that already exist on this rocky periphery against the Muskrat Falls hydro project on Indigenous Innu and Inuit territory of Nunasiavut (Labrador) and against fuel poverty on the island of Newfoundland, specifically. In the fall of 2016, a collection of Innu, Inuit, NunatuKavut, and settler community members, now known as the Labrador Land Protectors, breached the fence at the Muskrat Falls hydro dam construction site on the lower Churchill River and occupied the worksite for six days, only leaving when Indigenous and settler government leaders reached a deal to “assess” the methylmercury situation. The Crown corporation of the NL government, Nalcor, was billions of dollars over-budget on the mega-project and had refused to clear all vegetation from the flood zone. The Land Protectors insisted that without removing vegetation the risk of methylmercury contamination into the Churchill River, Lake Melville downstream, and the surrounding flora and fauna was inevitable. Methylmercury is a neurotoxin that can cause damage to the brain and central nervous system, and is thought to cause a form of cerebral palsy. It is especially damaging to fetuses and infants. The flooding of the lands around the Muskrat Falls dam would, the Land Protectors insisted (armed with studies carried out by researchers at Harvard University), poison the water and animals that are the main food supply for the people of Nunatsiavut. “Eat less fish!” tweeted Liberal mp Nick Whalen in response to protests voicing concerns over the possible poisoning of the region’s traditional food supply. 1

Living off of the land and accessing “country foods” is integral to Inuit and Innu culture, but fish is also a main dietary staple to many of those in the settler communities of Labrador and on the island of Newfoundland. In a province where mass organizing outside of political parties and non-profits has been minimal of late, the Muskrat Falls protests generated near universal support within the province, even amongst workers on the project itself. On the island, the proposed Hydro rate hikes to cover the cost of the near $13-billion dollar project led to demonstrations and an explosion of organizing. Settlers on the island, accustomed to subsistence lifestyles based around fishing and hunting, commiserated with the Labradorians frustration at having their country foods contaminated by methylmercury. Questions of reconciliation, Indigenous sovereignty, respect for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (undrip), and the duty to consult emerged. Some workers at the Muskrat Falls site from the island quit in protest of the ballooning costs that would bankrupt an already fragile province and force even more people to bleed out from its shores onto the rest of the continent. Others used the tools they could to support land protectors who took over the construction site for the dam, providing information, food, and blankets to those who occupied the site. A security guard at Nalcor offices in St John’s left his position in disgust after overhearing the derisive way executives talked about the Indigenous land protectors. Demonstrations and marches took over downtown streets, and protests were held at the Confederation Building, the Nalcor offices, and at the steps of the Colonial Building downtown. There were high levels of Indigenous-settler solidarity and worker-Indigenous solidarity the likes of which I have never witnessed in any of my previous organizing. Settlers on the island began to seriously come to terms with the colonial past and present of NL in a way that was more fulsome than at any other moment in the province’s history.

The struggle over Muskrat Falls continues—both on the island and on Labrador. Although the discontent with this project and the austerity budgets of the provincial government remain, it has not yet translated into a broader rising up, a broader struggle against the perpetual forces of neoliberal capitalism that finance and advance the environmentally and culturally destructive forces of the state. Through this lens of frustration and questioning I turned to Nangwaya and Truscello’s collection for answers. While the explicit answers I received were few, ample in this collection are words of wisdom, provocations, and considerations for those struggling through projects of liberation in their own communities, core or periphery.

The “obstacles to mass insurrection,” or even mobilizing and organizing that Nangwaya and Truscello reference in their collection, are what I find myself perpetually confronting in attempts to organize on the periphery of both empire and of radical cultures. In collaboration with the Labrador Land Protectors protesting the Muskrat Falls, in 2016 we formed Anti-Poverty NL in the capital city of St John’s. An effort to organize from, with, and as poor and working class communities, we tied issues of “fuel poverty”—our inability to pay for rapidly inflating home heating and electricity costs—to the struggle against the Muskrat Falls mega-project and to demands for Indigenous sovereignty. We demanded that no one should be forced to choose between heating and eating: a way to connect and conjoin the demands that provincial mega-projects not poison traditional Indigenous food sources with the insistence that fees for essential heating and electricity services in a nearly always chilly region must not impact the working classes’ capacity to feed themselves. In this way, we tried—and try—to build a collaborative movement that learns from Indigenous cosmologies of building relationships beyond the human, works to develop solidarities across lines of colonization, and implicates settlers in processes of decolonization that affect us all. In this way, we are trying to answer “now” to the question of “when will the Left listen” (33) that Praba Pilar and Alex Wilson pose in their chapter on Idle No More. The obstacle of building settler-Indigenous collaboration persists, but Pilar and Wilson offer us much to consider when they suggest that settlers can join 500 years of Indigenous resistance when we “release the locks [we] impose on alliance by releasing universalized eurocentric narratives and cosmovision, epistemic violence, and salvation narratives” (42) and instead work together in struggle to new ways of being, thinking, and knowing.

The global reach of the histories and present day struggles elaborated in Nangwaya and Truscello’s collection help us situate our movements on the edge of empire. But stories, much like grievances, are not enough to generate movements. Instead, we must have reasons to believe in collective struggle as well as concrete ways to move towards that collectivity. Isolation, as Khasnabish reminds us, is nothing less than a recipe for defeat. The book’s most useful contributions for me, then, are the ones that move us to projects, that push us to think through the intricacies and delicacies of organizing, of how we overcome certain obstacles and lay down the foundations to base our forward movements. To this end, the many contributors to the book offer important lessons to add to my own toolkit of practices or considerations, as our project resisting Muskrat Falls and fighting for the end of colonial capitalist domination continues.

It is the totality of the claims, more than any single chapter, in Why Don’t the Poor Rise Up? that prove most strategically useful for organizers, and taken together, the book doesn’t so much provide a roadmap to fomenting resistance as a series of waypoints along the long and often fractured path of struggle. For example, we are reminded that we must find foundations of resistance in the transgressive elements of the people’s culture—the things that already exist as sites of resistance but are not immediately read as such by counter-cultural perceptions of radical politics. This could mean amplifying both the history and present moments of commoning—sharing hunted and fished food, and also labour, outside of the circuits of capital—or revelling in the cultural resistances to enforced productivity by celebrating cultures of leisure—folklore, storytelling, song, and dance that are woven into the identity of Indigenous and settler communities here. 2 Such shared transgressive elements are a reminder that we are, “much larger than what the state and capitalism conceded” (156).

We are reminded to instill within our movements the traditions of revolt and revolution, and to develop political cultures of opposition and resistance, while engaging in political education and class consciousness. We are reminded to rethink what it means to be poor, to search for the “resourceful” already present in our struggles, to consider new expressions of solidarity, and to organize with that solidarity in mind. We are reminded to look to the “minor stories” in our midst and to refuse to let our struggles to be co-opted by charity work or bureaucracy, but rather by organizational structures centred on disruptive power. And finally, we are reminded to note our successes and share in the successes of others, while also reflecting on and healing from the trauma of our losses.

These are but the most relevant lessons of Nangwaya and Truscello’s work to my particular context and ways of thinking, about organizing and resistance at the settler colonial project’s rocky periphery. There are stronger essays and weaker ones, of course, and there is disagreement about whether “the poor” as a monolithic yet not fully defined group are actually rising up, rising up and failing, or not rising up at all due to the dominance of a violent capitalism and white supremacy. The book was comprehensive in its attempt to give a global picture but had limitations in terms of its depth and the concreteness of the advice I, as an organizer on the periphery, could take from it. That being said, it is a book I will go back to many times because so many of the stories in it are new to me (healing in the aftermath of the Grenadian revolution for example) and the lessons in each of them are important. From my island hovering over the freezing waters of the North Atlantic, the struggles in this text I have learned most from today may be different tomorrow; the lessons most relevant to organizers in Toronto may be different from those in Regina or Iqaluit. Yet the strength of Nangwaya and Truscello’s collection is that there are many stories and, therefore, lessons for everyone. •