British Columbia Fights Back: The almost-General Strike of 2004

Melissa Moroz, Gene McGuckin, Shane Calder, and Bob Wilson

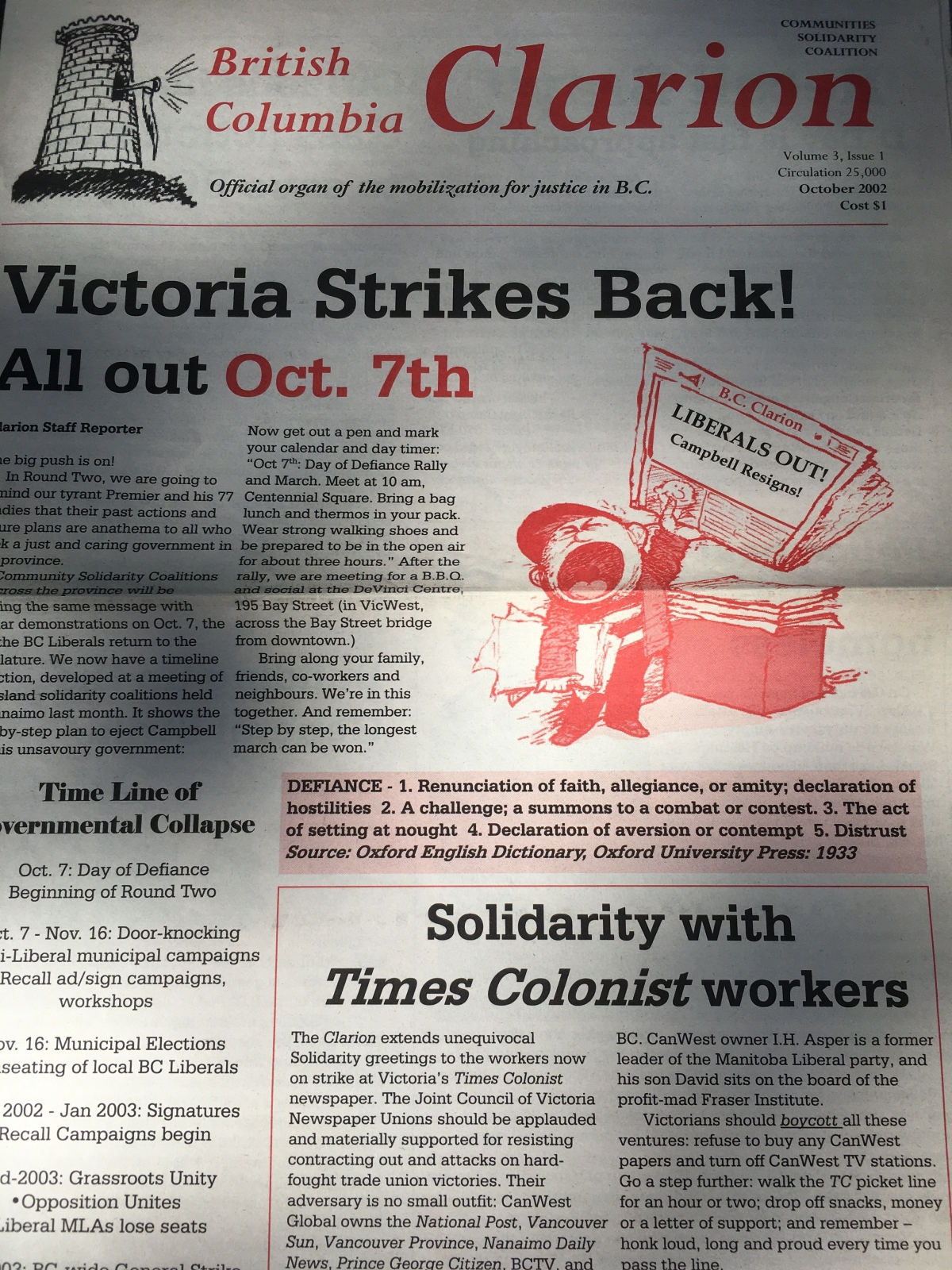

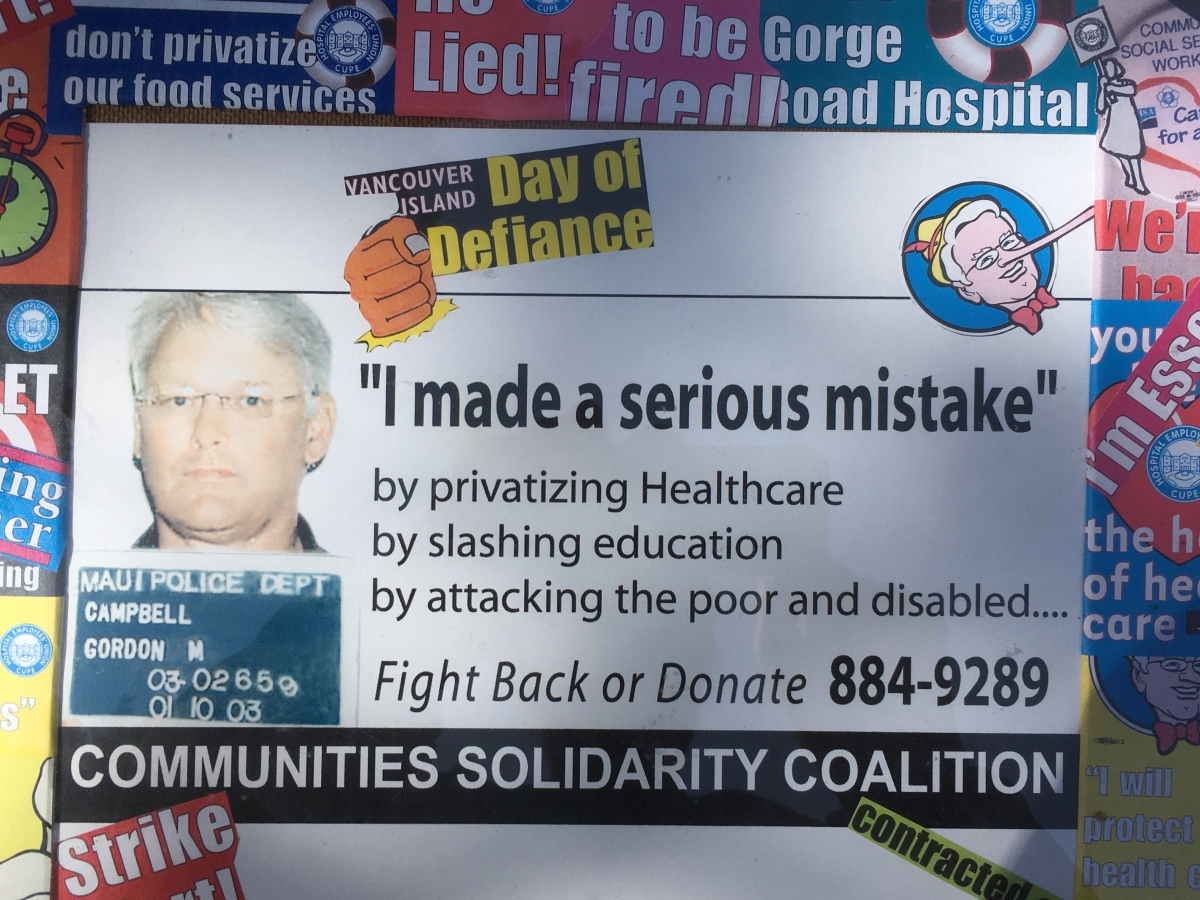

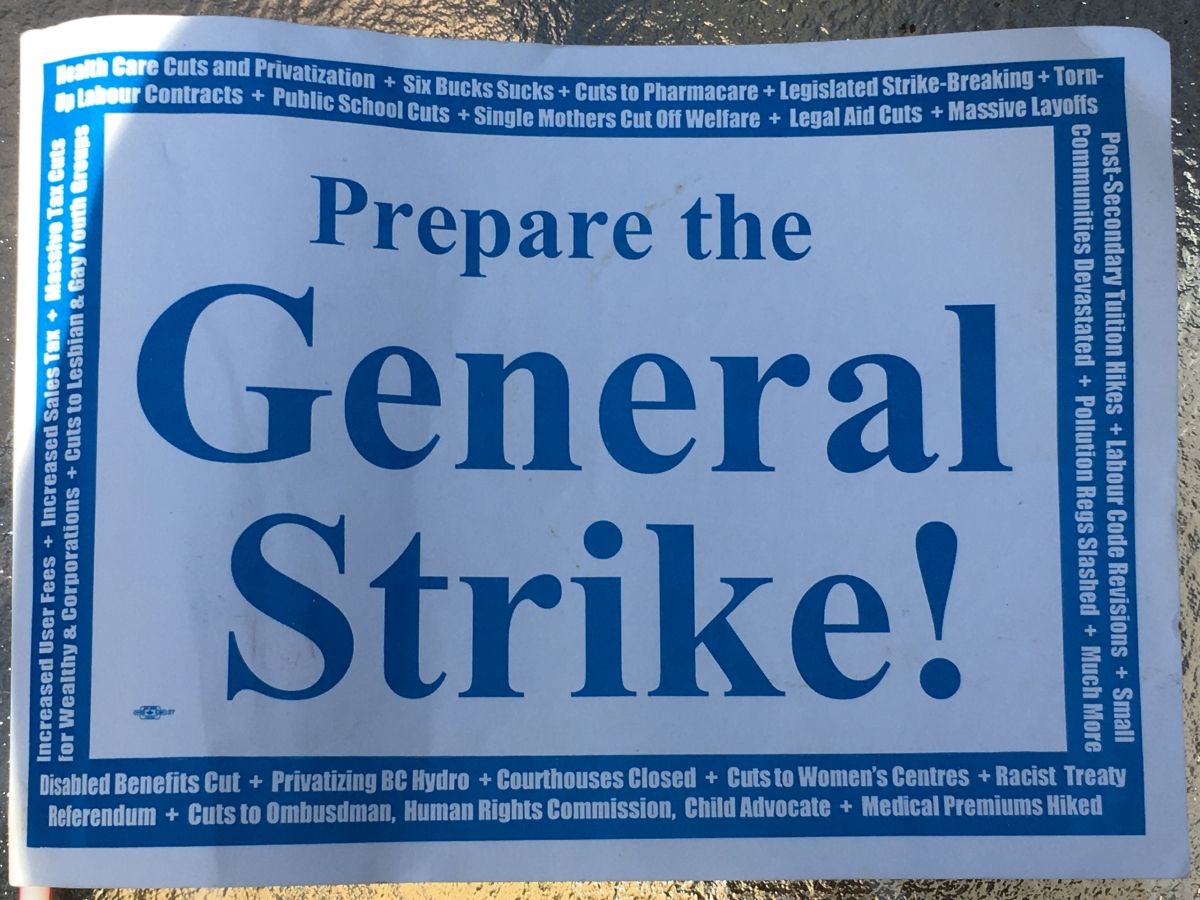

The election of the BC Liberal Party in 2001 sparked a resurgence of mass movement building, involving a high level of community-based organizing all across British Columbia. With the creation of broad coalitions involving traditional trade unions and militant community organizers, thousands of people mobilized when Liberal Premier Gordon Campbell instituted sweeping cuts to welfare, women’s centres, and education. The cuts also included direct attacks on organized labour. Specifically, Bill 28 tore up collective agreements with teachers and declared them an essential service to bar teachers’ unions from taking strike action. Then later, Bills 29 and 94 targeted the healthcare sector, which ushered in a new era of privatization through public-private partnerships, depressed healthcare workers’ wages and workplace protections, and resulted in 10,000 workers being laid off.

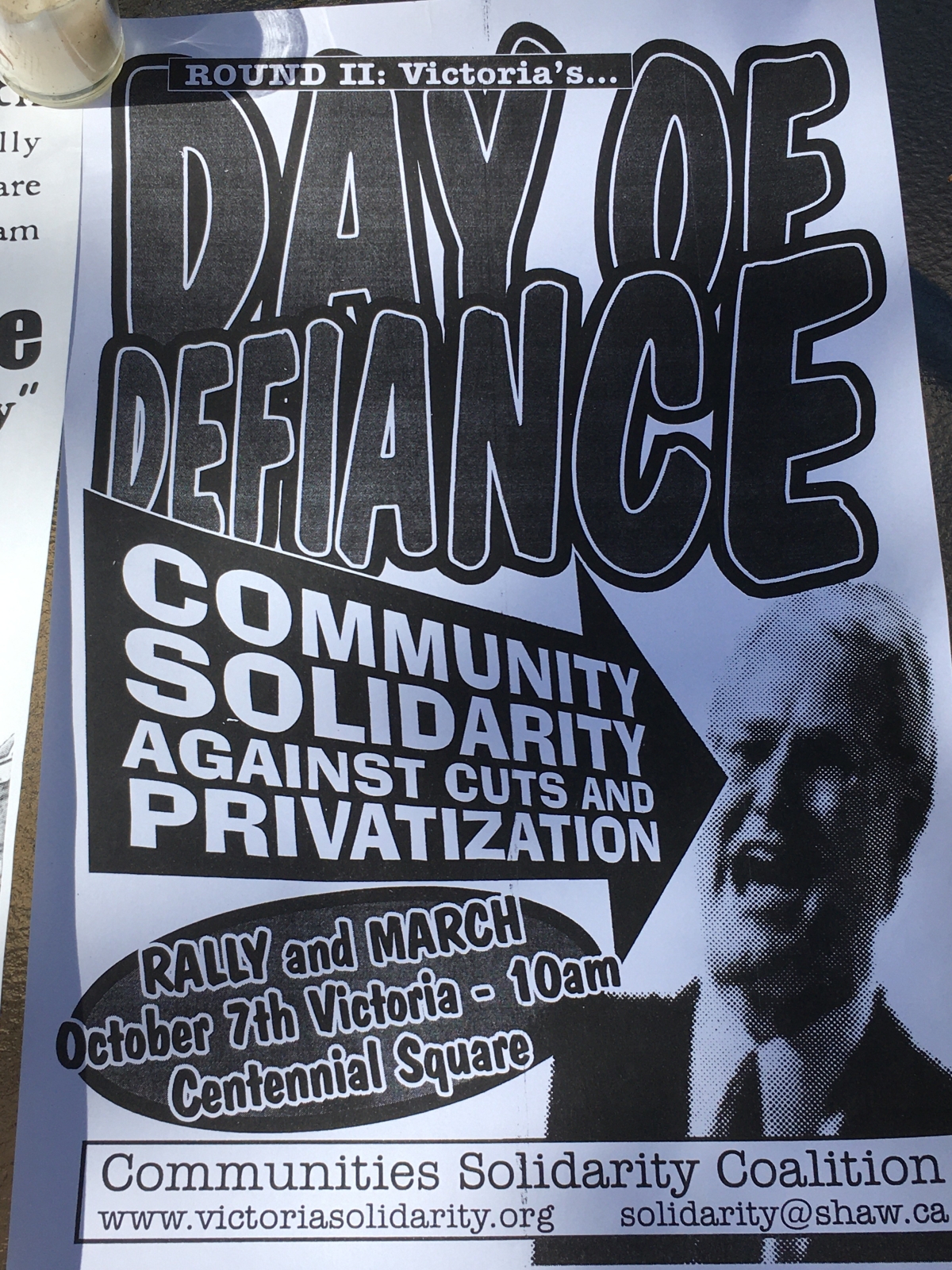

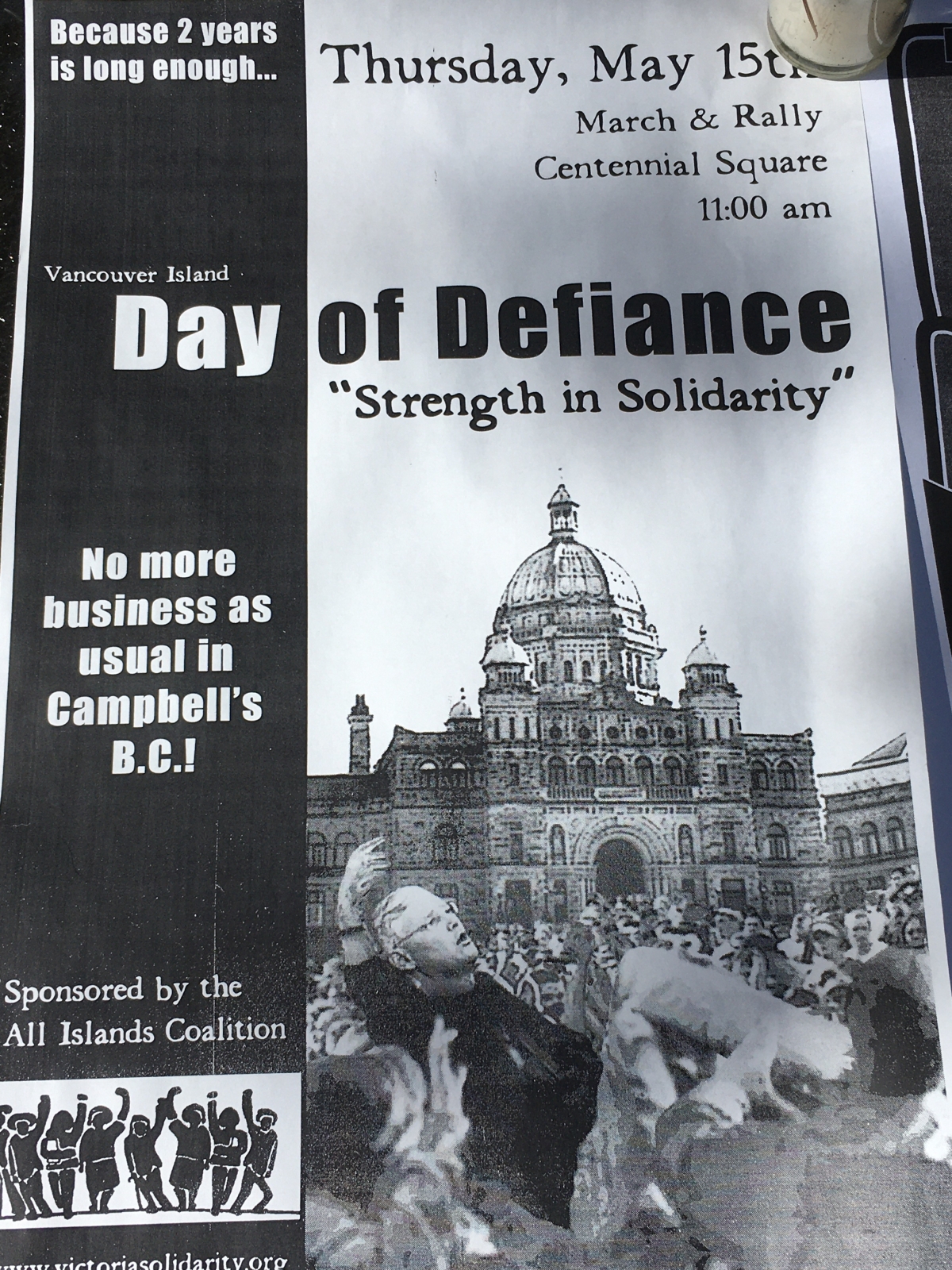

The responses to these cuts were diverse. New models of coalition-building saw BC labour giants working closely with and supporting grassroots organizers who were recently trained from organizing in anti-globalization movements. The largest of these coalitions was the Communities Solidarity Coalition. During an intense process of mobilization around a potential general strike in the province, a 10-week squat in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside became an especially important site of direct action and solidarity with the labour movement. By investing in community responses, the traditional BC labour institutions drew on the expertise of anti-poverty activists, feminists, socialists, and anarchists in the province, helping to mobilize in response to the austerity agenda of the BC Liberals. Rank and file support for a general strike was palpable from 2002-2004 but was ultimately called off. The result was the cementing of massive defeats in both the healthcare and education sectors.

In 2020, the New Democratic Party (NDP) gained a majority government, garnering optimism about shifts away from decades of austerity. In light of this shift we wanted to return to those days in the early 2000s and revisit the politics and lessons that emerged from within this moment of coalescence between organized labour and grassroots organizing.

In April 2020, Sharmeen Khan sat down with Melissa Moroz, Gene McGuckin, Shane Calder, and Bob Wilson who were active in this instructive organizing moment to discuss their reflections and lessons from this period.

Shane Calder is an activist and organizer born and raised on Lekwungen Territory (Victoria, BC). A perceptual curmudgeon, Shane’s current fight is to end the war on drugs and honour those who have been killed by it.

Gene McGuckin retired in 2008 after almost 30 years as a blue-collar worker at a unionized paper recycling mill in Burnaby, BC. He was president of his union local for 10 of those years and spent 22 years as the editor of a monthly local newsletter. He was politicized in the 1960s while living in the US participating in anti-racist and anti-war struggles. He came to Canada in 1970 as a draft dodger. He has also worked as a printer, a steamship stoker, a newspaper reporter, and an elementary school teacher.

Melissa Moroz works as a labour relations officer for a small union called the Professional Employees’ Association (the PEA). She enjoys working directly with members organizing for collective agreement improvements through bargaining and changes to the Employment Standards Act.

Bob Wilson lives and organizes in Victoria and has three children. He worked in health care from 1979-1993 and then worked for the Hospital Employees Union from 1993-2021. He was a member of Communities Solidarity Coalition from 2001 until 2010.

Can you please introduce yourself and talk about your role in the resistance to austerity in the early 2000s?

Melissa: I currently work for a union. I wore a few different hats during that time period. I was a staff person for a small union, Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) 4163, which was the education employees union at University of Victoria. My official title was “Recruitment and Communications Director.” I wouldn’t describe the local as particularly militant, but it had a few people on the local executive that didn’t want to be just a business union, so my position was created and I was organizing for them. I was also a grad student and was involved with the group Communities Solidarity Coalition (CSC) and a member of a few other groups as well that either sprung up ad hoc or were facilitated through the student society at the University of Victoria.

I was also organizing and supporting Camp Campbell, which was an almost month-long occupation on the lawns of the legislature in Victoria in February of 2002. We started the camp right after a Canadian Federation of Students (CFS) rally calling for reducing tuition fees. There were maybe a dozen activists mostly from University of Victoria and Camosun College who organized the camp. For us, the CFS march and rally at the legislature were not enough. We made and brought our own signs to the action to amplify more radical messages. The plan was, after the last speech of the CFS rally, we would set up tents, tables, and other infrastructure that we had hidden on the lawn of the legislature. There was no going back; within 15 minutes of the final speech, we had set up the occupation at the legislature.

Gene: I’ve been retired for 12 years, but now I’m working with the Vancouver Ecosocialists, which has a few people from the Vancouver Prepare the General Strike Committee in it as well. I’m also working with Burnaby Residents Opposing Kinder-Morgan Expansion. And, I’m a grandfather and still learning.

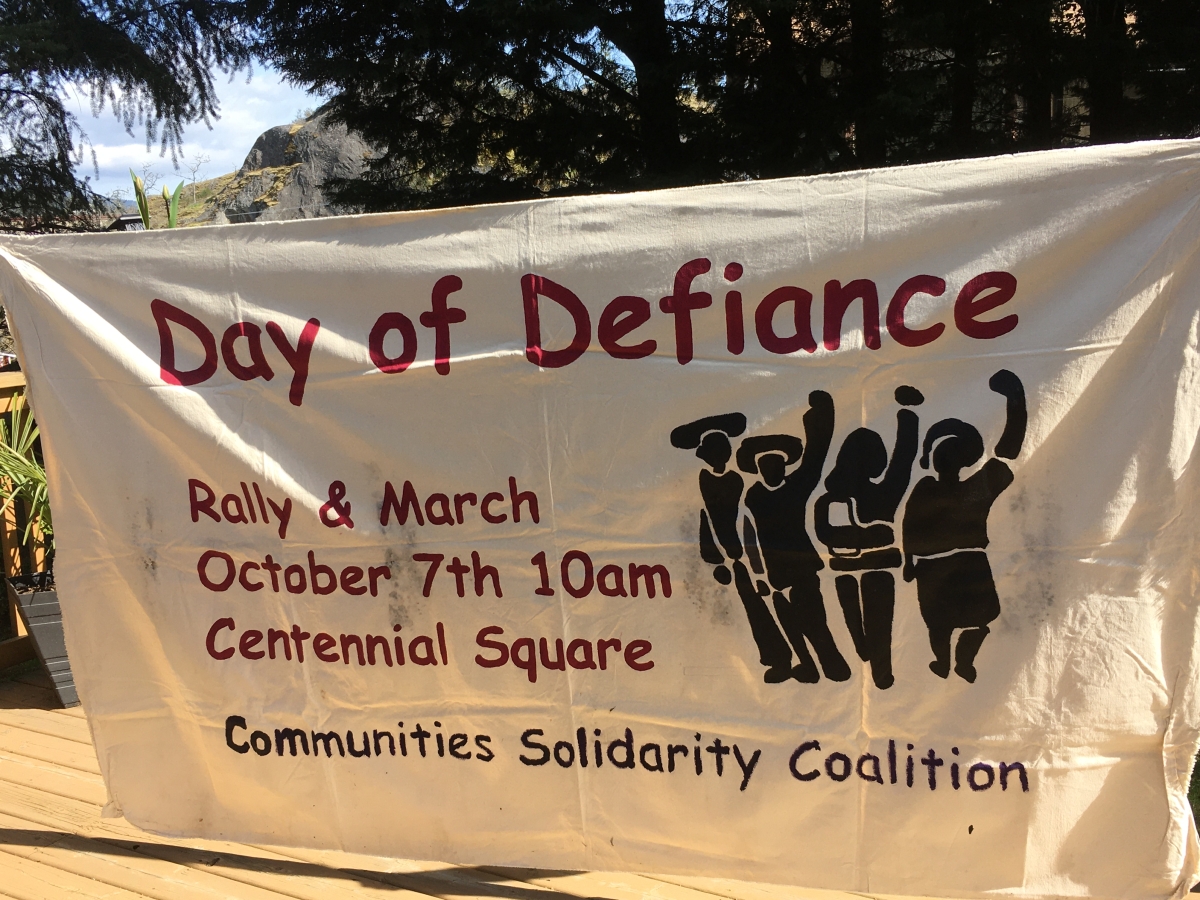

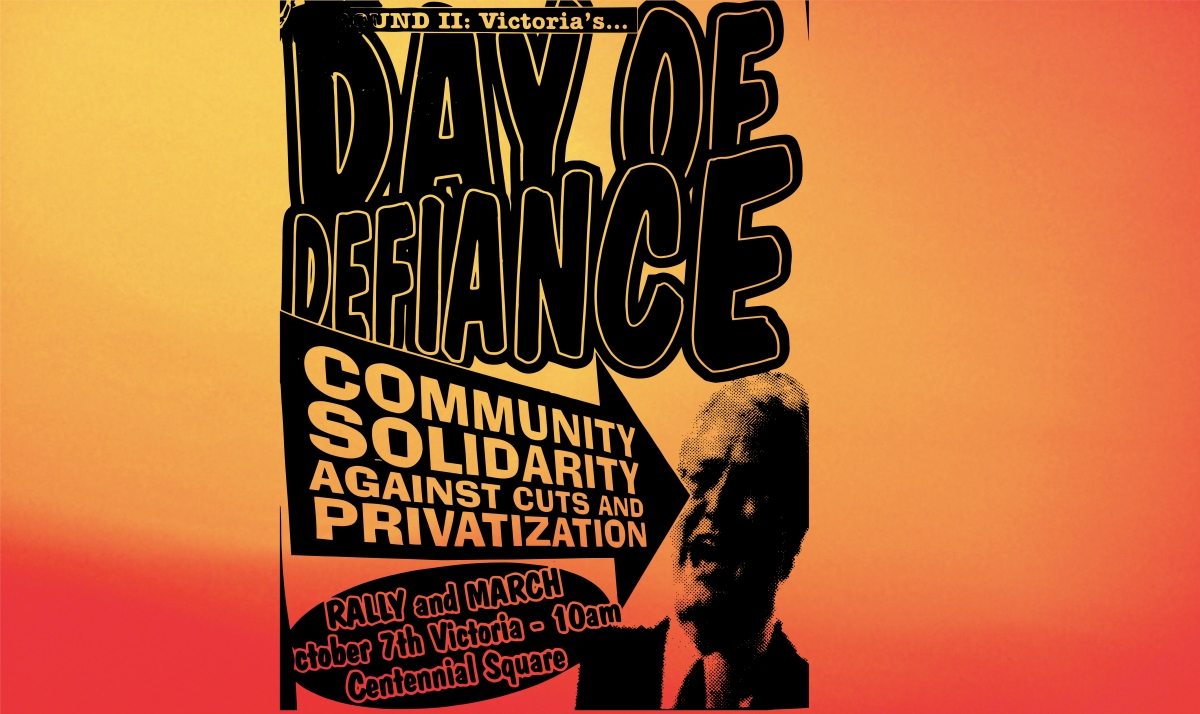

I met you all in 2002, during the October 7th Day of Defiance. At that time, I was the bargaining committee chair of a Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union (CEP) local at a paper recycling mill in Burnaby. I had been president of that local between 1986 and 1995 and I was the editor of a monthly newsletter that I started through the local in 1986 and published until 2008. In 2002, myself and a couple of other people decided to call a meeting of people interested in preparing a general strike. In May of 2002, there was a large demonstration in Vancouver against the austerity that the Liberal government was carrying out. So we pulled together enough people to have an impact on that demonstration and put pressure on the bad union leadership and on other unions to be a bit more radical. We handed out hundreds of leaflets calling for a general strike that were printed with the same colour of the BC Federation of Labour (BCFL) logo: blue ink on white paper. As planned, many union members at the demo originally thought the leaflet was from the Federation. We started a Prepare the General Strike Committee and held a number of meetings from early 2002 until we, with many more people, attempted to have a general strike during the May Day protests in 2003 (and any protests in support of hospital workers). Anyway, it was a great experience until everything got sold out.

Shane: I work for AVI Health and Community Services, a frontline service organization working in the midst of the war on drugs. I facilitate a coalition of the willing, so to speak, meaning a lot of people who are at the centre of the war on drugs such as people who are at risk of death and are criminalized by virtue of their drug use, as well as parents who have lost kids, service providers, social workers, and people in recovery. My work is largely educational for the purposes of consciousness-raising and gathering people into groups to create democratic engines that are necessary for political mobilization.

Back then in 2001, I was landscaping and trying to finish my degree in social work. We’d just come out of the anti-globalization movement and I became involved in actions against what the Campbell government was doing. When the nurses were mobilizing, I had heard that there was going to be a meeting to talk about a coalition and I remember thinking, “Well, we have to make sure this room is full of radicals.” And it just kind of went from there. I worked very closely with everyone on this call for a good number of years on all kinds of projects.

Bob: Back then, I had heard of Gene and we were doing the same stuff in Victoria. I worked for Hospital Employees Union (HEU) at the time, and in a staff meeting in December of 2001 I was assigned to cause as much shit as I could on a full-time basis. So, I went to the Victoria Labour Council meeting in December of 2001 and got a motion passed there to form the CSC. We met in January 2002. It came together quite well at the beginning, and we had quite a bit to do with the big BCFL rally on February 23, 2002.

There was also the emergence of Camp Campbell on the legislature lawn. One of my first tasks was to ask them to move to a smaller space so that the BCFL could have their rally. I felt we couldn’t ask them to leave but could maybe ask them to accommodate the rally and be part of it. So we got involved with supporting the Camp. After the giant May Day rally in Victoria, which was the first big event for the Coalition, I then was asked to go and shut down the town of Duncan as part of an escalating BC Fed campaign.

Melissa: I was also pretty naive in terms of organizing at the time, but the students that I had organized with were experienced enough to know that when we organized Camp Campbell we did that outside of the formal structure of the CFS. We knew there was no way that they would support an occupation of the lawn of the legislature, so we used the momentum of their Reduce Tuition Fees rally to set up our camp. I remember that they were supportive, but we knew to be cautious and not to rely exclusively on organizing with them because they would probably bail at key moments, which has some parallels to the BCFL. The BCFL built the camp a kitchen and that was a real boost of solidarity—as was having 35,000 workers join us on the lawn of the legislature!

Bob: Absolutely. And we had met right at that time as well, and I think a whole bunch of us knew we had to have our own plan outside of the labour movement, so that we couldn’t be shut down by them.

Shane: There were a couple of things that happened before this group formed that are worth mentioning. Geoff Plant, the attorney general at the time, orchestrated a public referendum on treaty negotiations. So we organized with Indigenous organizer Rose Henry and the now defunct Community Coalition Against Racism to gather in as many ballots as possible. As thousands gathered on the legislative lawn, we rolled up an old oil barrel and dumped bags of ballots, and people burnt them. This got them such bad press right out the fucking gate that they had to back down from the referendum immediately. It seems like a lot of the work we were doing was just trying to get them to back down on their promises, so there were no gains. They came out promising privatized health care and completely revamped education—it was a real slash and burn.

I think the government realized, “Oh shit, we can’t do that because these radicals are pouring out of everywhere and calling for militant actions like a general strike!” They pulled back really quickly. The large demo in February that Melissa spoke of at the legislative lawn was massive, and everyone came out. But at that rally, they realized their mistake because, at the next one they did in May, which Gene mentioned, they purposely put the stage on a hill, in a very inaccessible spot, and quickly tried to pull the militancy back.

Gene: Where we really made inroads was during the 2003 BCFL convention in Vancouver. A member in the Prepare the General Strike Committee, who was a member of the Telephone Workers Union, figured out a way to pull out phone numbers and emails for every single union local in the province. We used this list to contact 600 different places in BC—locals, federations, head offices, things like that—to tell them we were planning for a general strike. As the BCFL convention came up, we emailed out a model resolution calling for a general strike. During the convention, variations on that model had been submitted by 15 locals from six different unions and four labour councils. When we got to the convention, we managed to get daily caucus meetings organized and attended by people from dozens of different locals where we devised a tactic: since the resolution on the general strike would only be debated as one item, even though it had been submitted many times, we had people agree to speak about the need for a general strike during the debates of other resolutions, such as those on attacks on unions and social spending. As a result, the need for a general strike was put on the convention floor 30-40 times per day. After lunch one day, coming back from supporting the Woodsward occupation, the convention’s marshalling squad had been instructed to make sure no one went into the convention carrying general strike flags—which we had been producing by the hundreds and handing out at various events for weeks. But word of that made it to the back of the line and people just started tucking them in their briefcases and jackets. As the debates happened, people got up and waved their general strike flags. The BCFL leadership threatened the expulsion of people with general strike flags, but of course, they never followed through. We spent two to three years making life difficult for the bureaucracy at BCFL conventions.

What is fascinating to hear about is the willingness of major unions to work with militant community organizers and work behind the scenes to support grassroots organizing. What are your thoughts about that kind of collaboration with official union leadership and grassroots organizations?

Bob: What the labour movement has is money and when they put the resources into grassroots organizations, it goes a long way. I eventually gave up, but for a while, I was trying to get five of the larger unions of BC to fund a full-time community organizer role to help that relationship grow. I was a good example of that because I was being paid $80,000 per year to do that and I did a lot, so if they all paid someone like that or gave resources to groups so they could hire someone it could be done. But I’d say it comes down to established labour institutions’ fear of the movement; they need to be in control all the time and you lose control when you give power to the grassroots.

Shane: I have some mixed views around this. I have been on a lot of picket lines and I noticed the mainstream union movement abdicates any responsibility to the social good outside servicing the contract and their members. Not that there isn’t a place for that, but that is not inherently socialist. You need to be really strategic and we were able to do that in our work with the union. Some unions were supportive and really needed the support of the community, but some were duplicitous and kind of dangerous. Those near the top of union institutions are very protective of their power and have rules in place at their conventions that dampen, not enhance, democracy. Also due to their very close relationship to the NDP, they believe that the end result of the general strike has to be a change in government. So they ended up not supporting the general strike because they believed the NDP was not ready to take power. At the time, we were making the argument that we didn’t care who was in government, we needed to demand to stop the austerity agenda right at our doorstep. The NDP couldn’t get their head around that and neither could the leadership in labour.

Melissa: Most of the unions I’ve been involved with have been non-partisan and don’t have an electoral strategy. They may acknowledge that an NDP government is better than a Liberal one and do an analysis of what life was like under the previous government, but that is not an electoral strategy. Some unions have invested a lot of resources in an electoral strategy, but in general, a lot of unions are mostly focused on servicing their members. They’d like to be something more and may have activists in the executive or a strategic plan that speaks to getting out in the community and building solidarity, but it takes resources to do that. Where is the culture of organizing and being an activist union? It’s a shit ton of work and you need to know what that work looks like. You need to have a vision and imagination about another world being possible. You need to have those really brave people in leadership to stick their necks out and to talk about anti-capitalism—not just about how the system is broken, but to draw people into fighting for something bigger.

The best part of organizing within unions and what makes me most optimistic is that whenever I am tasked with calling union members and saying, “Hey, this action is happening,” or “there’s a picket line,” people are pretty consistently supportive. It’s just building those connections and that’s a lot of freaking phone calls and personal connections—it’s not just a Facebook group. When you had unions like the CUPE locals making the links between social movements fighting cuts and workplace actions, that’s when powerful relationships got built.

Shane: I’m not the only one who looks at Ontario and wonders where the fucking unions are and where the fight is, right? This could be my cynicism, but those people would rather focus on electoral strategy than create relationships with the community.

I still have memories of the almost general strike that got taken away. There are many differences of opinion on the success or failure of that time. Some people said we showed the Liberals people power and what we were capable of with the HEU strike and they won’t attempt that level of cuts again. But I also remember that people felt deflated and disempowered after the general strike was called off. Can you talk about the impact of calling off the general strike?

Gene: Between 1983-2004, it wasn’t as though there weren’t any attacks on unions or popular forces; after all, that was neoliberalism’s rocket rise. But, we didn’t have a significant struggle that was led by or acquiesced to by the unions because people remembered putting all their hopes into this incredible struggle in 1983 and then having six to seven guys at a fucking porch party in Kelowna calling it off. 1 In order to get people ready to risk hurting their families or communities, changing their routines, and taking time out of their lives, there has to be a chance of winning. But, then, they look around and they see our own leaders on the other side. The same thing happened again after 2004. Up until 2005, the BCFL would call periodic demos of tens of thousands of workers, every four to five years. And now, it has been 15 years since there have been thousands of us in the streets. Seeing ourselves and each other in the struggle together—not just me and my belly-aching friends who are upset about this—is another major component of believing you can win.

Shane: I feel movements have about an 18-month shelf-life. Something occurs, it motivates people, and they come together and there is a certain novelty in the new relationships, in the structures, and a sense of hope… but that dwindles. What was awesome about this struggle was that there were a number of events that occurred prior to and during that were all refreshing. That helped build a sense that new things were possible. For my generation, the student movement throughout the 1990s was a massive motivator. By 2002, there were a lot of activists with years of experience. There were notably women’s brigades, the anti-globalization movements, and anti-poverty days wherein the student movement met union activists who showed up to support them. Bob brought those people down and was involved very early on and no one knew each other, but bonds were formed. That helped us locally for a lot of years and was deeply motivating for thousands of people. So we were able to sustain our momentum past that 18-month cycle, but I would have to agree there was a real sense of betrayal after the failed general strike in 2004. It seemed pretty clear at that point that the unions were no longer behind the general strike. Even for a bit we were hoping that people would come around, but it didn’t happen, and any astute observer would note that wasn’t going to come back. We had put our eggs in that basket and it was over.

Bob: There was a lot of lost hope. On that May first, there was so much potential and if that couldn’t get us what we needed how do we ever build that again? For non-union people to be ready to walk off the job. . . it was a big task but I think it was possible. I remember stopping for gas and the gas worker said, “I’m walking out next week for the May first general strike.” So it really was an active betrayal; all it took was for top BC labour bureaucrats to meet in the same room and shut it down. We struggled a lot for four years doing a lot of good events and continuing that fight, but it just got smaller and smaller until the main activists just said, “we are done.”

Melissa: We had built this momentum going from village to village picking up people just to show up at the castle where they don’t let you in, but the response ended up being “ok we are all going home.” It was so hard; it was so deflating. We handed the leadership of the big unions a victory on a platter and they didn’t take it. I guess they saw things differently; they believed we weren’t organized enough to do it ourselves on that big of a scale. A general strike is hard to do without organized labour’s full support. They have a lot of power and credibility, so if they’re against us it makes it even more difficult.

Some workers, activists, and union locals held the line after it was called off by the BCFL, but it was too difficult without the numbers, strike funds, and threat of penalties. I often go back and wonder: “what was our plan had we been successful with the general strike and toppled the government?” I wasn’t thinking too much beyond that. We needed to build beyond just that moment and start to figure out that bigger plan.

Bob: Although it was a single issue general strike, if we pulled it off and won, people would have felt that power and taken the next issue on. You don’t need to take the government out: people were walking out to support the HEU, not on their own issues.

Melissa: That is true.

Shane: We put a lot of work into a list of demands. There was a fairly exhaustive process to build demands with housing, poverty, education, and so forth. We hoped that those demands would be galvanizing enough.

Gene: I disagree a bit that it was a single issue strike. In terms of what was publicly voiced, yes it was one issue. But you must have seen what I saw on the picket lines: all the people that drove by and honked weren’t honking because they were strictly union backers, but because we were fighting for their health care. They knew a whole bunch of things had been taken away from people across the province. I agree we don’t need a general strike that takes down the government, but you have to be open to the idea that people participating in it want to change the balance of forces—and what that all looks like day two, well, that’s for history to decide.

Speaking of history, the next year when there was potential, not for a general strike, but for huge confrontation, was when the teachers were out on strike and, defying legislation, 60 percent of the population supported them. That was some indication of people still being tuned in. But, at precisely the same time as 10,000-15,000 teachers and supporters were having a huge rally and forum at the Pacific National Exhibition grounds in Vancouver, [BCFL president] Jim Sinclair was asked during a radio interview if he thought the teachers would accept a package of back-to-work compromise recommendations that had been put forward by arbitrator Vince Ready. But instead of saying, “Well, the teachers are meeting today to consider that and have a problem with those number of recommendations,” he said to the entire audience listening, “I don’t see why they wouldn’t accept them.” This was a signal to everybody that the labour movement as a whole was out of the struggle and the teachers were on their own. They were crushed in the next few days.

I want to ask about how we deal with these cycles. Where we might have a period of a nicer neoliberal government, and mobilization is at a low until Conservatives enter and ramp up the cuts and then again, there are calls for a coalition and a general strike. Speaking from Ontario, many younger activists are curious about previous fights when the Harris Conservative government was elected. Right now you folks in BC have a new NDP government. Can you give some final thoughts to this circular pattern around provincial and city fightbacks against provincial governments and city councils?

Bob: One thing is to not put too much credence into history. It is good to know what worked and what didn’t, but it’s a new movement and it has to have its own hopes and goals. The bottom line is to never give up. I’ve noticed lots of good stuff going on over the last few years and it would take some sort of crisis to pull that together, but there has to be hope and there’s no reason to not have hope.

Gene: I don’t think it’s about whether there is going to be another crisis; we are living in crisis and it’s unfolding and expanding. There will be people who try to fight back against forces of oppression and create alternative ways of dealing with the crisis by putting together large coalitions. We can’t predict what is going to happen weeks from now or a year from now. You keep on keeping on and keep saying we have the power and show historical examples of when that was true. I wouldn’t be emphasizing the times that we lost. Although we should understand some of those losses and why our leaders sold out. I believe that rests on the fact that labour has only one strategy: electoralism. And they think that radical action by working people will make middle-of-the-road voters associate this with the NDP and therefore not vote for the NDP.

Melissa: With the COVID-19 crisis, all the HEU-related problems (such as the privatization of long term care) became more acute. It’s fascinating to watch things we’ve been fighting for so long like free transit and wage increases happen overnight. I never imagined a situation wherein the change could happen so quickly. Maybe it will spark a “wow this is possible, we can do these things but there has just been a lack of political will.” Sometimes you feel like you’re just repeating your message, “safe drugs,” “housing for all,” “public health care,” it’s like your song, right? And all of a sudden something happens and there are a bunch of people singing your song and you don’t know if it’s going to catch fire. Sometimes you have to keep pressure your whole life.

Shane: We were very good at making relationships with people and did a lot to ensure that we weren’t just having a protest but that there was always food and money on hand to help with people transport. We believe people shouldn’t pay out of pocket to protest, so we would fundraise. We would get paid for different things and that really helped and it doesn’t take a lot to do that. For a while, the unions seemed to really want broad-based support and that’s a vulnerability we can exploit. In the construction of those relationships, there was always a sense of “this helps us and this helps you.” But we all got savvy to each other’s games: the British Columbia Government and Service Employees Union (BCGEU) locked us out after one of our members wrote a scathing critique of the BCGEU—that’s all it took.

I would say start with locals, find where the union activists are, and work with them to figure out how to get resources into the community. It’s a very worthwhile endeavour and it’s more likely to succeed when the population is freaking out. When putting together a coalition, figure out who is the carrot and who is the stick, and organize committees for different tasks: someone to agitate, someone to go into the meeting and say “how can we all get along?” *