We Have Never Experienced Such Concern: Transnational Bonds of Solidarity from Minamata to Grassy Narrows and Whitedog First Nations

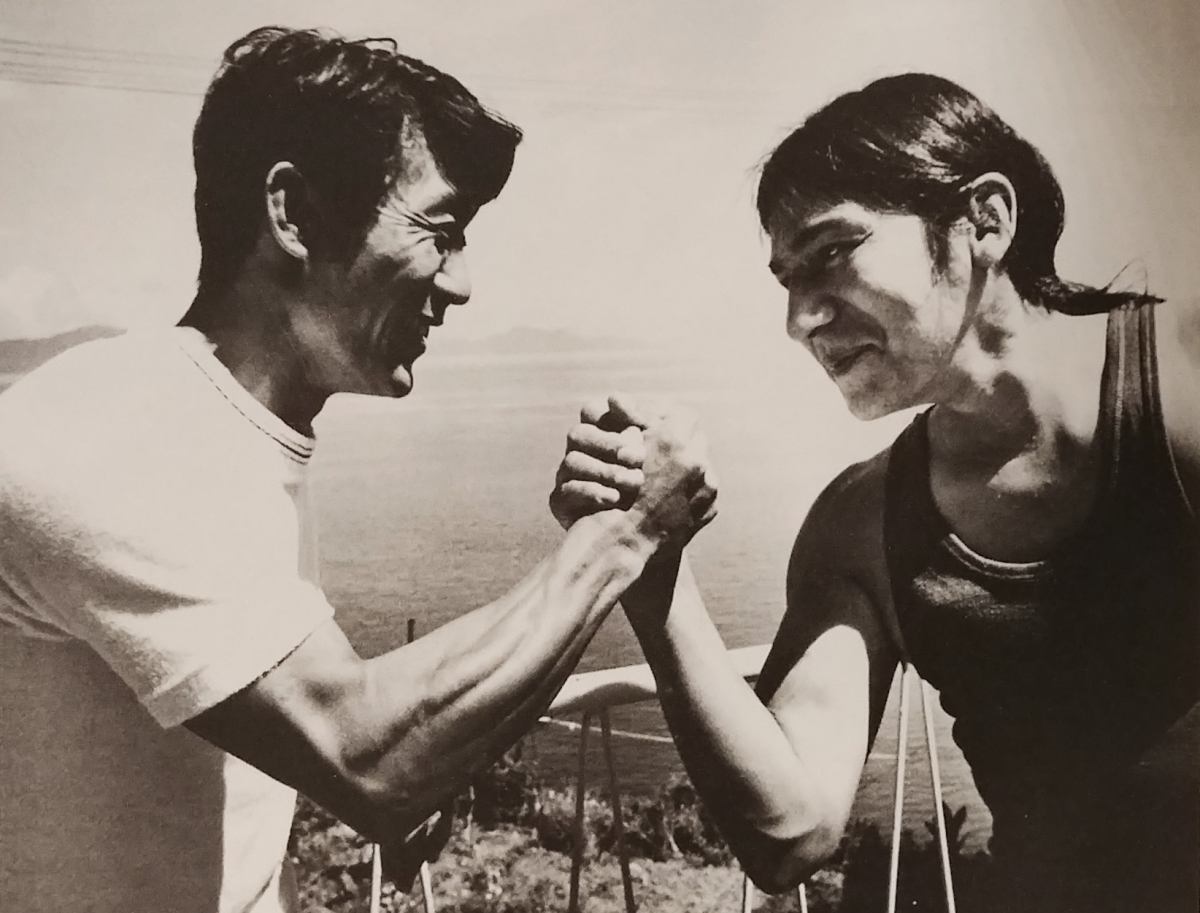

Tommy Keesick from Grassy Narrows teaches Teruo Kawamoto from Minamata the “radical” handshake, Japan, 1975 (photo by Dick Wallace in George Hutchison, Grassy Narrows)

“The racism has to be put aside. It’s not just an indigenous problem, it’s a human problem.”

CANADA’S COLONIAL ARROGANCE

“Thank you for your donation.” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s smug comment towards a frustrated supporter of Grassy Narrows First Nation at a $1500-per-ticket Liberal party fundraiser was caught on video and quickly went viral in March 2019. Trudeau later apologized for his response, made in the lead-up to the 2019 federal election campaign, but continued to stall on his government’s 2017 promise to build and fund a mercury treatment home in Grassy Narrows, also known as Asubpeeschoseewagong. Trudeau’s critics argued that his glib reply, while uncharacteristic of his usual “sunny ways” demeanor, actually showed his true colours. Indifference towards the wellbeing of Indigenous peoples and their traditional territories is par for the course for Trudeau, and indeed every previous colonial Canadian government.

This was only the latest episode in more than fifty years of mistreatment experienced by the mercury-afflicted communities of Grassy Narrows and neighbouring Wabaseemoong Independent Nations, commonly known as Whitedog First Nation. Community members have tirelessly campaigned to hold federal and provincial governments, as well as the culpable corporations, accountable for recklessly disregarding Indigenous lives and the environment. Their holistic vision of mercury justice includes cleaning-up the river system, preventing further environmental destruction by halting industrial logging, building the treatment home, and securing compensation for all people in mercury impacted First Nations. These activities are part of an ongoing process of asserting sovereignty over their land in order to restore Anishnaabe culture and wellbeing.

Facing significant pressure, Trudeau sent Seamus O’Regan, then Minister of Indigenous Services, to Grassy Narrows in May 2019 to broker an agreement. The minister showed up more than an hour late and put pressure on community leaders to sign a non-binding deal that did not meet their needs. When they refused, O’Regan left without an agreement. The government only offered to pay for 1/2 of the necessary construction costs and 1/4 of the operating costs for the mercury treatment home. Rather than putting the funds in a secure trust, as requested by Grassy Narrows, Minister O’Regan later presented a contract that said the federal government could walk away from the agreement with 30 days notice without cause and without consequence.

Following a series of grassroots actions by Grassy Narrows people and their allies, mercury justice became a major talking point during the federal election campaign. NDP leader Jagmeet Singh made a high-profile stop in Grassy Narrows and spoke about Grassy in his speeches and televised leader debates. Trudeau responded by saying that “money is not the objection” to moving forward with the mercury treatment facility, but made no specific commitments.

After the October 21 election, it remained unclear whether Trudeau’s Liberals, reduced to a minority government, would take a new approach to the file. After more than 50 years of denials and delays, mercury justice advocates refused to “wait-and-see”. One week after the election, community members from Grassy Narrows, including the sons of the late Chief Simon Fobister, travelled to Toronto to call for immediate action. In December, Grassy Narrows Chief Rudy Turtle blasted the Trudeau government’s “paternalistic” approach and lack of movement at an Assembly of First Nations gathering in Ottawa. Marc Miller, the newly-appointed Minister of Indigenous Services, asked to meet with Turtle the next day.

Finally, in April 2020 Grassy Narrows secured a historic $19.5 million agreement with the federal government to build a mercury treatment facility. Minister Miller promised that 30 years of up-front operating funding – estimated to be worth $68 million – would flow later, once the next federal budget could be approved, and could later be put into a trust. With repeated federal budget delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this has still not taken place at the time of writing.

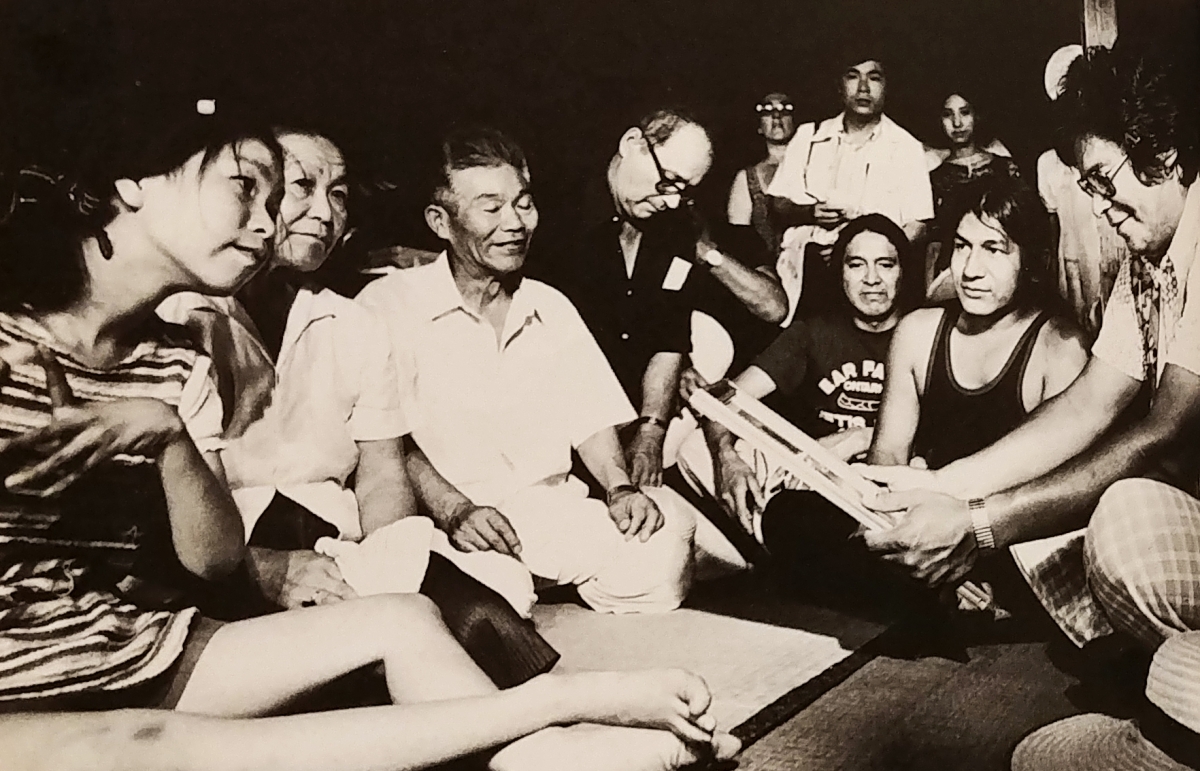

Bill Fobister (rightmost), Tommy Keesick (to his right) and Andy Keewatin from Grassy Narrows visit with Jitsuko Tanaka (leftmost), a Minamata patient in 1975 in Japan (photo by Dick Wallace in George Hutchison, Grassy Narrows)

TRANSNATIONAL BONDS OF SOLIDARITY

“We cannot think of your problem as a stranger’s problem. We Minamata Disease patients, as victim’s of Japan’s industry and government and capitalists, have these several decades been discriminated against by the world around us and have tasted poverty and physical and mental suffering … It will be a blessing if our long years of suffering can help you in even one single way.”

– Tsuginori Hamamoto

The state-sanctioned harm and neglect towards Indigenous peoples poisoned by mercury stands in stark contrast to the enduring bonds of solidarity these communities have cultivated with mercury survivors in Minamata, Japan. This transnational solidarity provides a crucial, but underappreciated perspective on how members of Grassy Narrows and Whitedog First Nation persisted in their campaign to secure mercury justice from Canadian settler governments and corporations. It is an example of a rich tradition that Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar, writer and artist Leanne Betasamosake Simpson refers to as “Anishnaabeg internationalism” in the 2017 book As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance. By leveraging their connection with Minamata, mercury poisoning sufferers here punctured the suffocating blanket of denials from Canadian governments of the 1970s, and developed a powerful relationship of mutual aid that they have sustained for over four decades. Their alliance emerged from a deep connection, forged by shared experiences of industrial mercury poisoning, state complicity, and devastation wrought upon their ecosystems, people, and traditional ways of life.

Left: Demonstration and memorial service led by Minamata patient families with members of a Chisso workers’ union joining in solidarity in 1970 (Center for Minamata Studies)

Right: Marchers with the Grassy Narrows River Run event departing from Queen’s Park in 2014 in Toronto (Samay Arecentales Cajas)

Mercury sufferers in Japan confronted the Chisso Corporation that shamelessly dumped mercury effluent into the Minamata Bay from 1932 to 1968, more than a decade beyond the initial discovery of what became known as Minamata disease. The poisoning of Minamata Bay destroyed local fisheries and afflicted thousands of locals with symptoms including numbness, muscle weakness, loss of vision, damage to their hearing and speech, and in more pronounced cases, paralysis and premature death.

When Indigenous people in Canada first complained about the symptoms of mercury poisoning, their concerns were ignored. Federal and provincial governments repeatedly denied that there was a serious issue and officials resorted to racist victim-blaming, suggesting that Indigenous people were suffering from the effects of alcoholism. It required incredible effort on the part of members of Grassy Narrows and Whitedog First Nations to break the grip of anti-Indigenous racism and pro-industry boosterism, which promoted toxic contamination of remote Indigenous communities as a fair trade-off for corporate growth and profits.

A turning point in the public understanding of mercury poisoning came when experts on mercury poisoning from Minamata, Japan were invited to come to Grassy Narrows in 1975. The Japanese scientists quickly corroborated the concerns of Indigenous peoples in Grassy Narrows and Whitedog. Soon after, Minamata patients made the trip to Canada, further underscoring the commonalities between their respective experiences. Minamata patients joined activists from Grassy Narrows for a protest on the steps of Queen’s Park, the provincial legislature. The strategic involvement of Japanese scientists and mercury survivors introduced an irrefutable voice to amplify their research and advocacy efforts (though the government still tried, referring to the scientists as “travelling troubadours”).

In turn, leaders from Grassy Narrows and Whitedog received an invitation to visit Japan later that year. Minamata patients were radicalized by their own struggle for justice and were driven by a desire to ensure that no one else would suffer the same way they did. They urged their guests to learn from their experience: “Please don’t repeat the mistakes we made in Japan … if you rely on [the company], the central government, or the provincial government – they will do nothing for you,” said Tsuginori Hamamoto of the Minamata Disease Patients’ Alliance. Underscoring this ethic of public pressure and direct action, they presented their guests with a loudspeaker. Tony Henry from Whitedog remarked, “We, the Canadian Indian, have never experienced such concern.” This comment can be understood as an indictment of an unbroken chain of colonial Canadian governments that claim to uphold their treaty responsibilities to Indigenous nations while simultaneously dispossessing them of their land, culture and even children. And rightly so, as the federal government has yet to take sufficient action to disprove this sentiment.

The relationship between these communities remains strong. Return visits by the Japanese scientists played an instrumental role in building a scientific body of evidence and drawing mainstream media coverage, such as a 2014 CBC report titled “Grassy Narrows: Why is Japan still studying the mercury poisoning when Canada isn’t?” Grassy Narrows people have used each successive report by the Japanese researchers to validate their lived experience, and as a springboard to raise their own voices through press conferences and creative public demonstrations. Sufferers have maintained direct relationships through regular visits and joint activities like conferences, as recently as February 2019. They have put mercury justice on to the world stage, calling for greater environmental protections and helping to pass the UN’s Minamata Convention on Mercury.

Judy Da Silva in Japan in February 2019 for a conference on environmental pollution and its social impacts hosted by the Center for Minamata Studies (Judy Da Silva)

NO MORE WORDS, NO MORE MEETINGS, NO MORE PROMISES

When mercury justice advocates in Grassy Narrows call for a treatment home to be built in their community, they refer to the existence of a similar facility in Minamata, Japan, one which some have seen and visited first hand. This facility served as the original inspiration for the demand championed by former Chief Steve Fobister Sr. during his hunger strike at Queen’s Park in 2014. Returning from visits to Japan, Grassy Narrows mercury sufferers have remarked on how in Minamata sufferers are treated with dignity, respect and even honour – a stark contrast to the denial, neglect, and racism the people of Grassy Narrows face when trying to access care in Canada. This internationalist perspective raises the bar for the justice that Grassy Narrows people know they deserve and helps to make the unrealized dream seem possible.

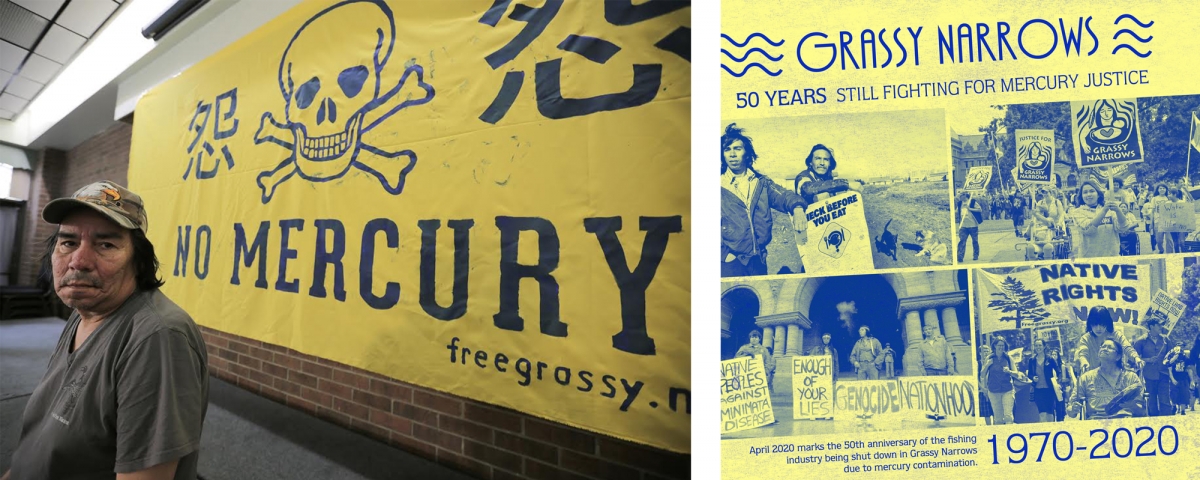

Left: Former Grassy Narrows Chief Steve Fobister Sr. before announcing his hunger strike in Toronto in 2014 (CBC)

Right: Graphic created to commemorate 50 years of fighting for mercury justice in Grassy Narrows (Free Grassy)

While the Minamata connection is important, it is only one part of an incredible legacy of resistance, which begins with the amazing strength, resilience and perseverance of Indigenous people, and key leadership from grassroots women and youth. Along with their special relationship with Minamata patients, Grassy Narrows people formed important alliances with Indigenous allies and non-Indigenous groups in Canada as part of their practice of internationalism. On their recent visit to Toronto, the delegation from Grassy Narrows held a press conference at the Workers’ Action Centre and later a protest with Toronto-based supporters outside of the regional office for the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC). Brian and Leroy Fobister, the sons of the late Chief Simon Fobister, were joined by current Chief Rudy Turtle, elder Bill Fobister, and grandmother Judy Da Silva.

Bill Fobister (left) and Brian and Leroy Fobister (right), outside of the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada in Toronto in October 2019 (Ryan Hayes)

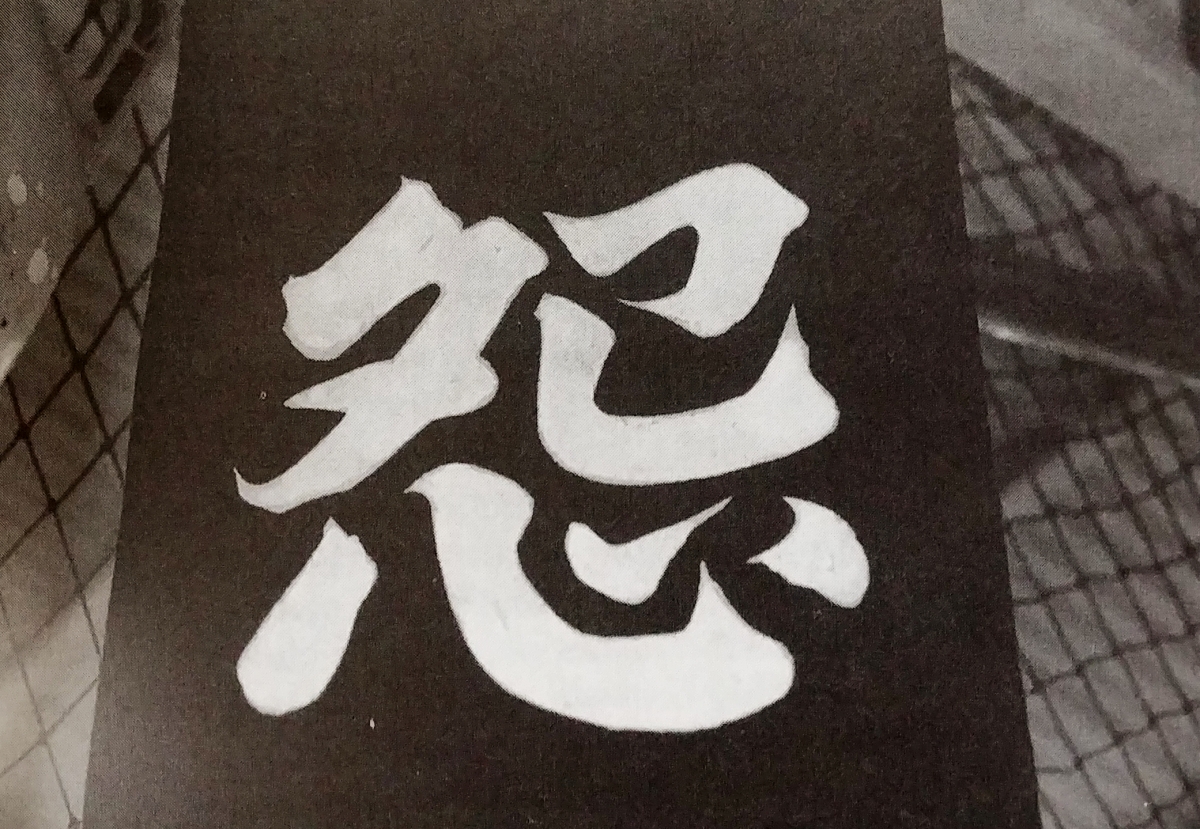

They had a large yellow banner with them, a fixture at most Grassy events and actions since 2014. Alongside the urgent “No Mercury!” slogan and the toxic symbol of the skull and crossbones is a less immediately identifiable Japanese character urami. The symbol, which became prominent in Japan during the Minamata struggles, is sometimes translated as “grudge”. The urami character appeared on mercury sufferers’ “flags of vengeance” in stark white paint on tall black vertical banners as part of their unrelenting campaign for justice. In much the same way, the people of Grassy Narrows have made it clear that their efforts to protect the health of their people, water and land knows no bounds.

A banner used in the Minamata movement with the character for urami (Keibo Oiwa, Rowing the Eternal Sea: The Story of a Minamata Fisherman)