Against the Mythologies of the 1969 Criminal Code Reform

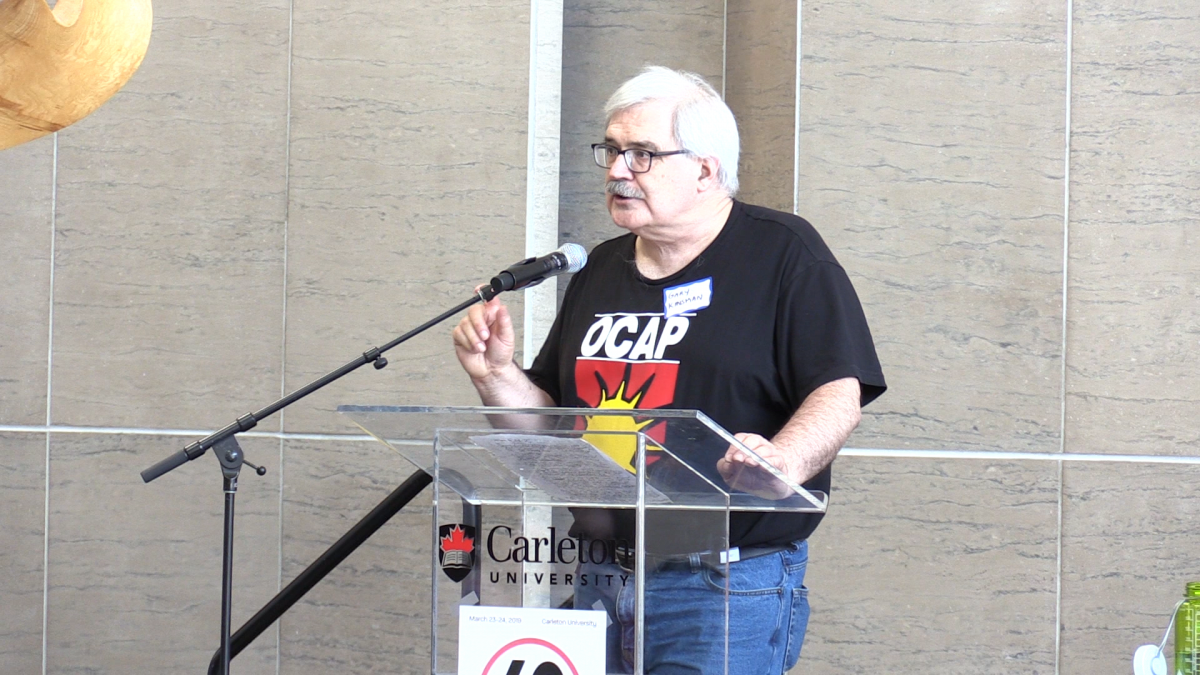

An Interview with Gary Kinsman

In June 1969, amidst the rhetoric of the “Just Society,” the White Paper on the extinguishing of Indigenous sovereignty, and the early years of state-sanctioned multiculturalism, the Canadian government passed an omnibus Criminal Code reform bill. The Omnibus Bill is often cited as the moment homosexuality was decriminalized in Canada, when Pierre Elliott Trudeau was benevolently trying to bring about equality for lesbians and gays, or when reforms established the right of women to access abortion and reproductive rights. None of these claims are accurate. Ryan Conrad spoke with Gary Kinsman in late March 2019, to reflect on the mythologies of the 1969 Criminal Code reform in light of recent state actions and how these acts of recuperation and co-optation impact left queer organizing strategies in the present.

Gary Kinsman is a long-time queer liberation, AIDS, anti-poverty, and anti-capitalist activist living on Indigenous land and in solidarity with Indigenous struggles. He is currently involved in the AIDS Activist History Project, the No Pride in Policing Coalition, and the organizing committee for “Anti-69: Against the Mythologies of the 1969 Criminal Code Reform.” He is the author of The Regulation of Desire: Homo and Hetero sexualities (Black Rose, 1996), co-author (with Patrizia Gentile) of The Canadian War on Queers (UBC Press, 2010) and co-editor of Whose National Security? (Between The Lines, 2000), Sociology for Changing the World (Fernwood, 2006), and We Still Demand! (UBC Press, 2017). His chapter “Forgetting National Security in ‘Canada’: Towards pedagogies of resistance” was just published in Aziz Choudry’s edited collection Activists and the Surveillance State (Between the Lines/Pluto, 2018). He currently shares his time between Toronto and Sudbury, where he is Professor Emeritus at Laurentian University. His website is radicalnoise.ca.

How and why do you position yourself as anti-1969?

Not everything that happened in 1969 was bad. The Stonewall Riots took place in 1969, which are an origin point for contemporary queer liberation movements. There were also workers’ rebellions around the world. What the federal government is trying to get us to remember about 1969 is their narrative of one particular slice of that gigantic history, the 1969 Criminal Code reform. They want us to accept that this entailed the total decriminalization of homosexuality. Sometimes they say partial decriminalization and sometimes around abortion they also will argue it was the legalization of abortion, which of course it wasn’t at all. There was no decriminalization of homosexuality in ’69. Only two of the many offences used against queer sex were addressed, no offences were repealed, and you could only engage in these if you were 21 and over with one other person in a very limited “private” realm. Charges against consensual queer sex escalated after ’69.

Why I position myself as anti-1969 is to oppose this official celebration of what the Canadian state did for us in 1969: allegedly the decriminalization of homosexuality and major access to abortion services. In late August of 2018, while having lunch at Glad Day Bookshop in Toronto, Tom Hooper and I had this idea to have an event opposed to the celebration of the 1969 mythology. We formed a broader organizing committee and put together a conference on March 23rd and 24th in Ottawa. The conference had two different dimensions. One was as a fulcrum through which to do broader popular education against the mythologies of the 1969 reform. The other was to organize the conference itself. One of our central objectives was to put the 1969 reform in a much broader social context such as, for example, the White Paper on the annihilation of Indigenous sovereignty and the emergence of less overt forms of racism. That is, the explicit racism of immigration policy that said whites were preferred was replaced with a points system that was still operationalized in a very racist way, and the initiation of Canadian state multiculturalism that validated ethnic/cultural differences, but did not recognize in any way social or class inequalities. We also put it in the broader context of Pierre Trudeau’s central project of the so-called “Just Society.” We wanted to point out that this “Just Society” was not about a just society in terms of ending social inequality or anti-poverty measures; rather, it was about support for individual rights and was based on the destruction or limitation of social rights for Indigenous peoples, the Québecois, workers, and other people organizing collectively.

Can you give some examples of how the government is celebrating the 1969 Criminal Code reform and how they function?

There are a number of different ways the federal government is facilitating this official celebration. To start, it has given $770,000 to EGALE (a mainstream LGBT rights group), most of which has been used to fund a documentary film that Sarah Fodey is producing, titled Sex, Sin and 69. I, along with many others, refused to be interviewed for this documentary for two basic reasons. First, I asked for clarification about whether it was going to be independent of EGALE and I could not get it. I also wanted clarification that it was adopting a critical approach to the 1969 reform. They could not clarify that beyond saying that it was going to include a “diversity of opinions.” I’m not interested in being involved in a project that could be used to glorify or mythologize the 1969 Criminal Code reform.

There is also money from Heritage Canada that was used for Winter Pride in Ottawa. Although this funding led them to initially focus on the 1969 reform as being the decriminalization of homosexuality, when we raised critiques they shifted to describing it as the partial decriminalization of homosexual acts, which at least is more specific. It also looks like Heritage Canada funding led Pride Toronto to initially suggest that the 1969 Criminal Code reform would be the central theme for Pride Toronto this year. We responded to that with a lot of energy and they shifted their focus to the celebration of Stonewall. But a lot of Prides are being approached by Heritage Canada funding suggesting that “You’re going to get funding if you’re going to promote this perspective of the decriminalization of homosexuality.” There was also funding given to various Pride Committees across the country to do flag raisings to celebrate ’69 as the decriminalization of homosexuality. This may have a bigger impact on smaller Prides that are much more dependent on this funding. An event was also held in Calgary on May 14th to commemorate the 1969 Criminal Code reform. Again, we organized and Tom reminded them of the Goliath bath raids in 2002. We have had some success moving organizations at least partly based in our communities away from that official celebration of ’69.

The Canadian mint also produced a $1 coin that will commemorate the 1969 reform in a very disturbing way. The coin design suggests, using the slogan of equality, that there is some sort of connection between what happened in 1969 and equality that has supposedly now been achieved 2019. Of course, there was no equality in 1969 and there still is none in 2019 despite major transformations as a result of our movements and organizing.

These are some of the ways the Canadian state is attempting to get people to remember 1969 in this mythological way: as supposedly the year that Pierre Trudeau—as a gift from above—gave us the decriminalization of homosexuality. We are contesting and challenging that history-from-above narrative and will continue to do so.

It seems that there are connections and parallels between the 1969 Criminal Code reforms and the more recent official state apology by Justin Trudeau, which dovetailed with the settlement of the class action lawsuit by former LGBTQ public servants and military personnel fired from their jobs, “The Expungement of Historically Unjust Convictions Act,” a new omnibus Criminal Code reform bill, and a national LGBTQ memorial. This is clearly legacy-building of the Trudeau political dynasty. What are some of the other connections and parallels that you see?

First, it is important to understand the three different components to the apology and its limitations. One of the components was Justin Trudeau’s actual statement, which had lots of limitations and gaps and is also a very white apology. For instance, he never apologized for the intensive state surveillance of LGBTQ organizing in the 1970s and early 1980s. The second part of the apology was the class action suit and redress for people who had been purged. At this moment in time, the claimants have just received the minimal amount of $5,000 despite their lives and careers being destroyed. They may have to wait for another year to get the greater redress they were promised. Part of this process includes the memorialization fund. I am not sure exactly what is happening with that, but it’s probably going to be skewed along the lines of these mythologies rather than the experiences of people who were purged from the public service and military. The third component is the legislation that was supposedly going to provide a mechanism through which people could get their Criminal Code convictions for consensual homosexual acts expunged. However, it is very difficult to apply for, and it doesn’t cover offenses, which the gay and lesbian historians’ group vociferously argued needed to be included, such as the Bawdy House, indecent acts, vagrancy, and other offenses. It also includes a discriminatory age of consent set at 16 even though during many of those years the age of consent for heterosexual sex was 14. And yet, they’re wondering why so few people are applying for it. They later introduced Bill C-75 to try to get rid of antiquated and unconstitutional laws, but it is still in the Senate and has not been passed. We did manage to go to the Justice and Human Rights committee of the House of Commons (the same infamous body preventing people from actually testifying in regard to the SNC-Lavalin fiasco) and with the support of Murray Rankin from the NDP, we argued for specific amendments, including repealing Bawdy House laws, vagrancy, and indecent acts. At the House level, the Bawdy House laws and vagrancy were added, which means that the earlier legislation around expungement could now actually include these if the bill is passed. We are still pushing on repealing indecent acts.

The apology was, in part, the result of the organizing from below by the We Demand an Apology Network, comprised of myself, other people who have done research on this, and people who were purged from the public service and military. But the way it has operated, and the context within which we are now organizing against, is basically along the lines of an apology from above: “We have apologized for this now so you should forget about it. Don’t think about what we did to you in the past and become part of the contemporary Canadian nation state without any major transformations having taken place.” In other words, beyond the apology being a process to facilitate socially organized forgetting, they have also used it as a way of bringing middle-class, white layers within our communities into firmer alignment with the Liberal Party and the nation state. For instance, EGALE, in its infinite wisdom, gave its very first leadership award to Justin Trudeau for saying “I’m sorry” decades too late. This is not the first time EGALE has done work to bring white middle-class people into collaboration with the Liberal government. The problem with the apology, as well as with the celebration of the 1969 reform, is not simply that they were limited, but that they are both attempts to re-organize our communities against movements that are critical of the Liberal Party’s approach and have pushed for more radical changes. As I mentioned, at the very same time as the 1969 Criminal Code reform you had, under the same rubric of the “Just Society,” the attempt to extinguish Indigenous sovereignty with the White Paper. Indigenous resistance put a stop to that. At the same time as the apology and some limited attempts to get rid of some of the laws that have criminalized consensual queer sex, you see once again, state agencies attempting to destroy Indigenous sovereignty, this time, however, through the means of establishing it as a form of sub-municipal governmental authority. So, as they try to create this progressive veneer around LGBTQ issues, they are also centrally going after Indigenous struggles including over sovereignty, pipelines, fracking, water, and more.

These are attempts to reconstruct class relationships within our communities to favour those people who are on the side of the police, corporations, and the Liberal government. Beverly Bain did this very interesting presentation at the anti-1969 conference where she argued that the types of surveillance, purges, and exclusion campaigns that went on against lesbians and gays were part of the same campaigns against Black activists. Now you have campaigns against Black (often Black queer and trans activists), anti-racist, and anti-police organizers, prison abolitionists, and those of us seeking more radical social transformation who are cut out of the social fabric as the “deviants” and “security risks.” You can read some of what is going on in Pride Toronto this way. First, you had attempts to expel Queers Against Israeli Apartheid. More recently, you have had successive attempts to go against the membership’s decision to keep the organized and institutional presence of police out of Pride, which includes Pride Toronto’s acceptance of funding from Public Safety Canada. The initial installment is $450,000 to study police/queer relations all across the “Canadian” state. They want to reconstruct relationships in our communities to align Pride Toronto and various different organizations on the side of the police against us. This has incensed Pride committees and other people across the “Canadian” state. They want to construct those of us who are opposed to collaborating with the police as “the problem.” There is an attempt to use the moment of the apology, along with the 1969 mythologies, to re-align politically in a classed and racialized way relationships within our communities against those of us who want more radical forms of social transformation, against those of us who want to continue to organize against the police, and against blood bans, HIV and sex worker criminalization, and other struggles.

Can you speak further about resistance to this kind of social organization of forgetting as well as some of the impacts of state repercussions on queer/trans left organizing today? How does the anti-1969 conference in Ottawa fit within this?

Challenging the social organization of forgetting is based on the resistance of remembering our radical activism. I really don’t like doing that much work within state relations. But I think in a certain sense when we are pressing, persistent, and building alliances beyond what are usually built, we are able to win some limited victories within those sets of relationships. In terms of the anti-1969 conference, organizing against that mythology has provided a fulcrum to bring together people who were not only critical of that account of what happened in the historical past, but also against the same type of social forces organizing in our historical present. It has produced very interesting alliances between sex workers, more radical or militant queer and trans activists, queer and trans activists of colour, Black activists, and some Indigenous activists. It is also helping us to build the relationships, alliances, and networks which will sustain a new and different way of organizing for trans and queer liberation that is no longer trapped within these narrow rights frameworks—no longer trapped within the ways in which state relations want to define us or want to lay out for us, what the terrain of struggle is—and that begins to contest and move beyond state relations.

The reorganization of social relations amongst queers and the diminishing of the queer political imagination through actions of recuperation by the state: this seems to be particularly dangerous. The state is taking a proactive role in re-engineering how we relate to one another as marginal subjects, how we remember what has been won and by which means, as well as how we continue to imagine and strive towards a radically queer future. It seems really daunting and scary in a way, and although this type of recuperation is not new, it seems accelerated and scaled up at this particular historical moment thanks to the imagined anniversary of the decriminalization of homosexuality in Canada.

I think the stakes are quite high right now, partly because the whole rights mythology—the rights “revolution” that so many people have been left out of—has created this notion that somehow we are already there, that we are already fully equal especially with same-sex marriage. The disjuncture between the liberal, white middle-class notion that we’ve already arrived, that we don’t need anything more, is one of the reasons why Black Lives Matter Toronto’s (BLM-TO) beautification of the 2016 Pride parade is totally incomprehensible to people within that mind set. If we have already arrived, why are people disrupting the party? The racist notion operates this way: if Black people are constructed as being outside the community, as “others,” and gay people are coded as white, how can Black people actually be a central part of the queer and trans communities? Of course, BLM-TO was initiated and fueled by the energy of queer, trans, and genderqueer people, but this white gay racist imagination can’t even conceive that. We need to go back and re-think things with those people who have been excluded from the rights revolution as well as to challenge identifications with the Canadian state and the idea that rights struggles were ever going to achieve everything we needed. We are talking about multiple groups of people: people of colour who are queer and trans; people on the streets; young people who get expelled from their families; working class and poor people who can’t afford to be part of that white middle-class; people who are HIV positive who are criminalized; sex workers; people who use drugs; people living with various forms of disabilities and more. And we need to make connections between them and start conversations about how to reunite in more radical ways, and by radical I mean getting to the root of the problem. We need groups that can actually engage in battles for queer and trans liberation that are not seen as separate and distinct from all the other struggles for liberation that are going on in people’s lives, that grasps how intertwined and interconnected they are. Thinking about the anti-69 conference we had in Ottawa, some of its unique features are an important part of this. One was a very firm commitment to oppose settler colonialism, which I think was more profound than other events I’ve attended. A real attempt was made to prioritize the voices of people of colour, especially of Black queer and trans people. Not that we did any of this perfectly, but I think that trying to establish that as a sort of baseline for organizing is something that we actually have to build on and learn more from.

There are still tensions there. Take Rinaldo Walcott’s insightful critique of how focusing on anti-69 can still be trapped within the state form. I think that’s a very legitimate critique. How can we organize without being trapped within various strategies or regulations of the Canadian nation state? Clearly, it’s not simply about the Canadian nation state. Everything we were talking about at the conference had a much broader diasporic and transnational character to it. We have to figure out how we are going to displace that centering of state relations. And obviously when challenging the central celebration of the Canadian state, there are ways in which even our opposition can begin to mirror that and get trapped within its shifting forms even though that is not our intention. As John Holloway suggests, we need to simultaneously organize within, against, and especially beyond state relations.

We have to challenge the mythologies that are trying to construct the notion that the white, middle-class queers have achieved everything they ever wanted. I don’t think that is true, but what it has made visible is the class and racialized struggles that exist in our communities and the ways in which state allied forces like EGALE crystalize this division. Racialized class divisions among queer and trans people are much more visible than they were ever before, but it’s still difficult to name them because we still have to shatter the mythology of “community.” Community is not a bad word, but the way in which community has been mobilized is often to privilege white middle-class layers to become spokespeople, those who have the proper language and credentials to be able to speak for the community. We need to start to challenge that in very profound ways. As I discuss in my recent work on “The Making of the Neoliberal Queer,” it is not adequate to use the term “queer” in and of itself as a radical declaration; elements within queer theory and activism have operated to separate our struggles from racialized class struggles. We need to name, challenge, and struggle against the emergence of this neoliberal queer layer that has these white middle-class characteristics.

How did the anti-69 conference succeed in bringing these people together and raising these kinds of questions?

We didn’t have much time to organize it. I don’t think we actually brought the organizing committee together as a whole until the end of September, so we actually managed to do something quite significant in a relatively short amount time and on a relatively small budget. I would have liked for more people to have been there, more activists and students, but by and large it was very successful. It had an energy and uniqueness to it, a sense of people building networks and political and social connections that was really crucial. We are going to try to keep people connected as an Anti-69 Network. Our first project was to challenge the launching of the 1969 commemorative loonie on April 23rd at the 519 in Toronto. We did extensive media work, held a successful media conference and some of us crashed the Liberal Party rally where they launched the loonie. We are hoping that this network can continue doing education and activism. It was really weird at the conference where people were approaching me asking “when is the next one happening?” At that point in time, as an organizer you’re certainly not interested in thinking about that, but there were a number of people who approached us asking that. The experience was important enough for people to feel a sense of “more of this needs to happen.” I’m not sure it needs to take place in the same type of venue. We have to figure out ways of keeping these conversations and that type of organizing alive. I think it’s a crucial resource. What we established was something very important. It’s not a solution in and of itself, but it begins to provide us with some of the resources to develop an alternative way of moving forward.

I found it interesting that during the closing panel there was a bit of, “What do we do next? Let’s not be just another conference…” I found it a totally bizarre question because everybody in the room was already doing stuff. For me, the conference was an opportunity to reconnect with folks I hadn’t seen in a while who are doing great things and hearing what they are up to. But also, to solidify relationships with people who I want to be more closely connected to. I got to build better relationships with people whose work I’ve used in the past when I’ve taught or to think through complex questions.

There was a real constraint on us financially when organizing for the conference. It was only a day and a half, and much more of what you’re describing could have happened if it was longer. There was limited time for those things to happen, but I think they did in lots of ways. Sometimes it happened in individual sessions when people realized they had common interests or someone gave them a new idea. Some happened in the collective context of planning. We tried to have an event that was not simply academic, but also had major activist connections. For many people it was a unique event and that’s partly why you had people asking what comes next. In some ways they were saying they don’t just want to have conferences like we had in the past, but gatherings that are more like this one or events that get us thinking not only about the past, but also get us thinking about struggles that are happening in our historical present. If we had to do it again, I think we would try to make it longer so that there were more of those relationship-building opportunities. There needs to be broader ways in terms of how to keep that relationship building alive, and those conversations, practices, and activities alive and connected. There is a real hunger for them all over the place. There is actually a real need to get into these types of conversations of relationship and movement building in a different sort of way. I don’t think people are finding the past ways in which more radical people have related around queer and trans organizing satisfying. I think we need new and different ways of moving. What that will look like exactly, I’m not entirely sure.

For those who missed the anti-69 conference in Ottawa last March, where can they go to learn more about the network, upcoming events, and access tools to start conversations in their own communities?

The best way of keeping in contact is through our website: anti-69.ca. In particular people should check out the Frequently Asked Questions we have put together that develops our major critiques of the ’69 mythologies. We are also on twitter: @Anti69ers. Soon we will also have both video and audio of a number of the conference presentations online via our website, so they will be widely accessible as educational materials. If you want to be added to the Anti-69 Network list please email me at gkinsman@laurentian.ca and you will find out about all our upcoming events. If you want to organize an anti-69 event in your community, please contact us.