Strike and Reclamation

Building Power in the Fight Against the Corporate University

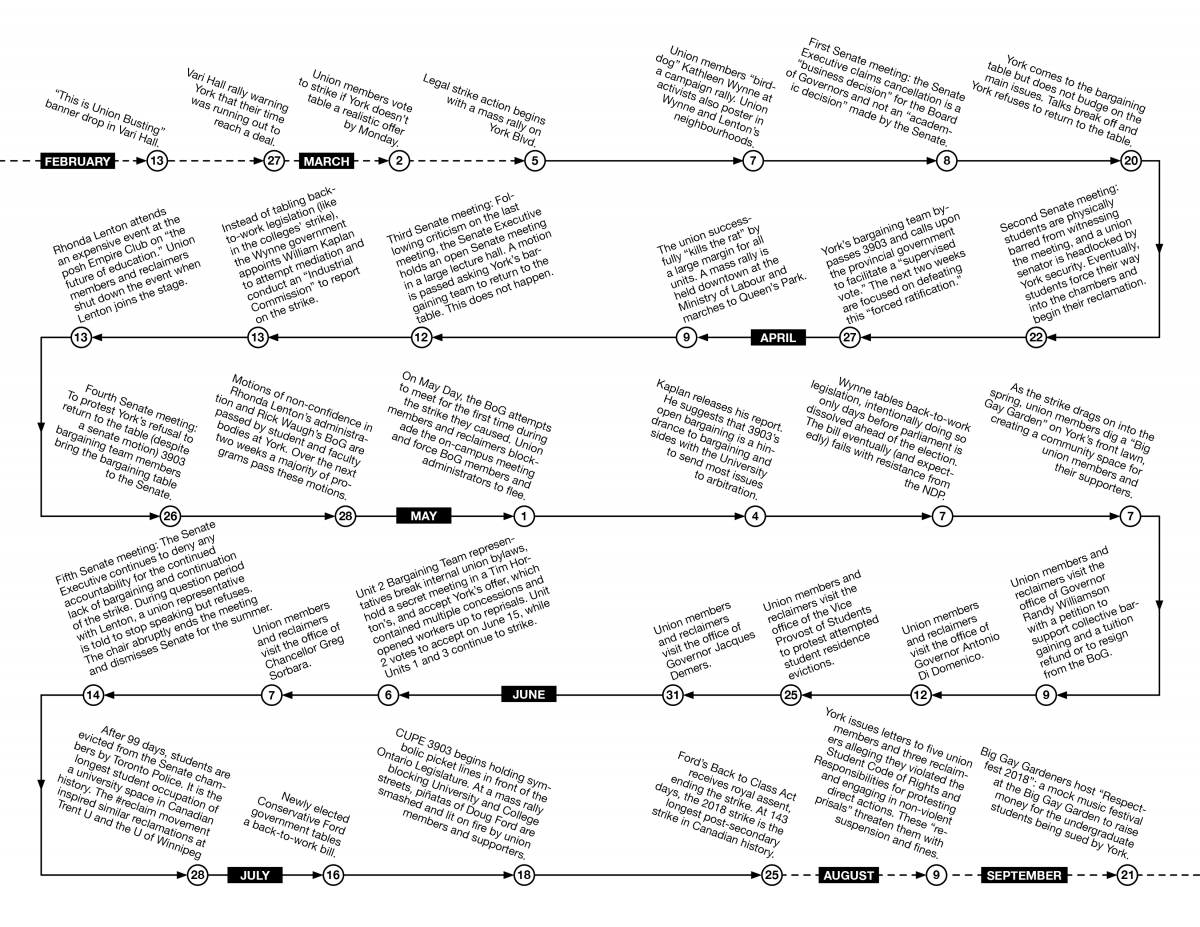

On March 5, 2018, members of CUPE 3903, the union representing contract faculty and teaching assistants at York University in Toronto, voted to take strike action against York after months of bargaining with the university had stalled and concessions remained on the table. Over the next 143 days, the university continued to stonewall the union until the newly elected Doug Ford provincial Conservative government circumvented the process of collective bargaining to pass unconstitutional back-to-work legislation on July 25, 2018.

Over the course of this protracted struggle, hundreds of workers maintained eight physical picket lines and an organizational and communications headquarters while undergraduates in support of the teachers reclaimed and continuously occupied the university Senate chambers for three months. Union members were also engaged in bird-dogging Liberal Premier Kathleen Wynne and the creation of an unsanctioned community garden—the “Big Gay Garden”—at York’s front entrance, while union members and undergraduate “reclaimers” engaged in civil disobedience, disrupted official university events, and visited the offices of the Board of Governors to hold them accountable to the broader community. After the strike, York University administration pursued reprisals on eight student-activists for their organizing during the strike using the student code of conduct. York eventually lost its suit against the “York Eight” when a court ruled that the university violated several of the defendents’ legal rights. Meanwhile, the Ford government has mandated the implementation of “free speech” policies on campuses across Ontario while the results of the forced arbitration have led to losses by CUPE 3903.

For this roundtable I sat down with Chelsea Bauer, a bargaining team member of CUPE 3903; Karl Gardner, executive member and chief steward; Susannah Mulvale, a rank-and-file organizer; and Karmah Dudin, an undergraduate student activist and member of Reclaim YorkU; to reflect upon last year’s fight against the corporatization of universities in general and the fight at York in particular.

Karl Gardner is an organizer and PhD candidate based in Toronto. He is a member of No One Is Illegal-Toronto and works with Upping the Anti. His political and academic work mainly focuses on migrant justice, Indigenous solidarity, and social movements in Canada.

Chelsea Bauer is an active unionist and staff representative in the post-secondary sector who believes that member-driven union activism and a strong student movement are vital as the post-secondary sector ramps up to challenge the Ford Government.

Susannah Mulvale is a PhD student in Critical Studies of Psychology at York University. She is currently Co-Chair of the Trans Feminist Action Caucus of CUPE 3903 and a Councillor for the York University Graduate Students’ Association. She is also an organizer with the Foodsters United union drive.

Karmah Dudin is a student at York University and a labour organizer with CUPE 1365-2, involved primarily with solidarity work and organizing student workers on campus. Karmah has had experiences challenging the corporate nature of the university via direct action and running to be the undergraduate representative on the Board of Governors at York University.

What is the current state of postsecondary educational politics in Ontario? What does the strike at York University reveal about the organization of universities, their governance, and contemporary approaches to bargaining?

Karl: York is an important microcosm for what’s happening in post-secondary education, not just in Ontario, but across Canada. We’ve seen a clear centralization of administrative power on our campus over the last 15 years. As public funding wanes, the university administration has taken more control to manage university finances and growth through mechanisms like corporate fundraising, attracting private investment, enforcing austere budget models, implementing performance metrics for departments, and stacking their Board of Governors with member who privilege corporate interests over community interests.

To achieve this, the number of administrative positions at York has ballooned over the last decade or so. In 2003, York paid $10 million in administrative salaries, and they’re paying $26 million now: that’s over a 150 percent increase. Students and CUPE 3903 members paid for this. We represent student-workers who pay tuition to our employers, contract faculty who are forced to live contract-to-contract with little job security, and researchers and graduate assistants. To punish student-workers––those of us who pay tuition to complete our studies while teaching part-time––universities have been increasing tuition as a way to make up for lost public funding. In Ontario, tuition has tripled since 1994, making post-secondary education increasingly exclusive and making students’ lives after graduation defined by debt repayment. And unfortunately, this is where international students really get screwed because their tuition is unregulated, so they’re charged even more money in order to access the same education as those with full citizenship. As a response to this downloading of the costs of education from the government onto students themselves, student debt has risen 40 percent over the last decade, and Ford’s recent changes to the provincial student loan structure are just going to make this worse. 1

In addition to tuition increases, there has also been a nationwide trend towards precarious teaching work on campus. Contract faculty are doing more and more of the teaching on university campuses across the country but are being denied the wages and job security of the tenured faculty they are replacing. Of the new academic jobs that are being created nationally, a recent study showed that 50 percent is contract work, and 80 percent of those contracts is part-time. So, at the same time that we see universities spend more money lining the pockets of the central administration and selling off more and more of the university to corporations, we see the erosion of learning and working conditions for those who actually make universities function.

Chelsea: It’s getting harder and harder to be hopeful and to see universities as positive spaces of change. And Doug Ford is merely accelerating the things that were already happening to make it so much worse. How do we deal internally with the university administration to make sure these changes won’t amplify the already difficult situations taking place on university campuses: the precarious work, the student debt, the declining enrolments?

Susannah: And all the decision-making at York goes on behind closed doors. The administration uses the rhetoric of “consultations” to justify their actions, but it consistently feels like the broader community has zero input on the decisions that are being made. Or if we do give input in these processes, it’s just so the admin can say they listened with no meaningful action.

Chelsea: It is disconcerting to me to see how much influence the Board of Governors has on decision-making processes, priorities, and hiring. The only group at York that wanted Rhonda Lenton to be president was the Board of Governors. Looking back on everything that’s happened, we now know that they wanted her for a very specific reason. She wasn’t going to cave or falter. She was going to do what needed to be done in order to make sure that the union didn’t gain any more momentum. And she enabled the university’s bargaining team to avoid meeting with the union at all, so that over the course of the 143-day strike, our bargaining teams spent all of two days across from one another at the table. The power is so centralized that even tenured professors are being excluded and decisions are being made, not only behind closed doors, but behind closed doors with six people for an entire educational corporation. How sustainable is this model? What does the university in 10 to 15 years in Canada look like?

Karmah: In terms of trying to build power in these spaces, I ran for the undergraduate representative on the Board of Governors during the strike. At the time, I was both running a campaign and occupying the Senate at York. I got some good publicity, but that was by accident. It was sketchy, and not even implicitly but explicitly. When I asked for the official election results multiple times, they were withheld from me. And my opponent even broke the campaigning rules—which I complained about multiple times—but nothing happened. They knew that, if I did actually win the popular vote and the results were public, denying my appointment would be a huge deal. So they purposefully kept these processes opaque.

I think there are opportunities here to actually infiltrate governance, and not just by their standards, but through holding mock elections and trying to actually push people into the governance that way. I think it’s worthwhile, especially if the goal is to push university administrations to respond to direct democracy and to take up certain ethical or political stances.

In their first year of rule, the newly elected Conservative Doug Ford government has introduced dog-whistle “free speech” policies, cancelled free tuition for low-income students, cut student loans, and tried to slash the budgets of progressive student groups by attacking mandatory student fees. How do you think labour and student movements should respond to these attacks?

Susannah: Speaking from the perspective of the York University Graduate Students’ Association (YUGSA), we’re currently trying to build coalitions on campus across the different groups that are affected and amongst other universities. The Canadian Federation of Students-Ontario (CFS-O) passed a motion to start organizing toward a general student strike, which I think is the direction that we need to be headed. We can look to the Québec student strike in 2012 for how to start mobilizing and planning for this, but we can also learn from the lessons of the 3903 strike. Currently at York, the student unions are focused on educating the student body about the changes. At first, people were very confused about what the provincial changes meant and didn’t really understand what was going on. We’re trying to combat the Conservative government’s vague “for the students” propaganda and to create a sense of urgency about student issues. We’re tabling, doing classroom talks, and trying to plan a rally for the end of the semester. Eventually the goal is to gain enough momentum so that you can have a walkout and work towards a student strike.

Karmah: I’ve talked to others who are also a part of the coalition building, but my worry is that the undergraduate community at York feels disconnected from the CFS or York Federation of Students (YFS). They don’t think of themselves as union members in that way. Do you find that there could actually be a realistic capacity to build towards a strike?

Susannah: I agree with you at this point, in terms of student disconnect and apathy. And it’s just not in the culture of undergrads to identify with their student union, or they simply don’t know that they are part of a union and that their union is there to provide all the services they have access to at the university. But the only way to change this is to literally get out there and start talking to people.

Chelsea: This comes up in my day-to-day all the time as I’m bargaining with a faculty association at another university in Ontario. I found that, often, union organizers get stuck in circular and reactive modes of organizing, which can add to the confusion of an already complex situation of university de-funding. But if you approach the situation with a centralized plan where everyone has a part to play, it’s a lot easier to manage.

For example, what if all the unions on your campus collectively petitioned the administration to uphold the use of student fees, despite the Conservative government’s attempts to undercut these services? Then you could organize a mass campaign to get a majority of undergraduate signatories. Key to this strategy is our ability, collectively, to pressure our administrations to actually look out for our interests because currently they’re complicit in the gutting of our institutions by not stepping up and fighting.

Tenured professors have a role to play here as well and need to become vocal advocates for job security in a precarious market. I know that there might not be a lot of union-friendly professors on campus, especially tenured professors, but you have to make it everybody’s issue, because if they don’t fight with us now, then they’re next. These cuts have an adverse effect on what students are working towards and the resources they have on campus. It’s important to frame the many issues we’re all facing, not as individual problems that have to be overcome, but as a collective struggle where we have to work together. Shitty governments come and go, but the university has a role here to step up and make sure that it takes care of its own community.

Karl: We’re in dire need for cross-sector solidarity, not only within the post-secondary education sector, but across other sectors affected by Ford: public school teachers, health care workers, migrant workers, legal workers… the list goes on. We need to see more militant job actions, workplace organizing that goes beyond those already on our side, actual disruptions to business-as-usual, and displays of a critical mass of people not willing to stay idle in these times. These things are a must right now because the parties in power know that rallies come and go. Public opinion can be fickle; today people are outraged and in a month people forget or move on. It doesn’t matter if it’s Vari Hall or if it’s Queen’s Park or the Ministry of Education; people can simply attend and leave those rallies feeling like they’ve done their part. But these brief protests are so easy to ignore these days. We can’t throw out these tactics, but we have to also engage in the longer-term project of deep organizing. We rely too much on tactics that come and go like a flash in the pan, which makes momentum difficult.

Similar to the rally-organizing model, petitions are signed and forgotten with the hope of change, but hope alone bears no fruit. How do we grow membership and social investment in key organizations on campus? Karmah is right: a lot of undergrads probably don’t even think of themselves as part of a union. How do we start changing that conversation so that the average student thinks of unions as a vessel of our collective power? And how do we get students to not only identify this way, but actually act on this identity to defend it?

Karmah: Maybe I’m just pessimistic, but at the moment I don’t see any effective way that we can push back. We should still do whatever we can, but I see this as an opportunity to really question, “how do we think long-term here?” because we’re probably going to see another turn of the political cycle where the Liberals come back after people realize Ford is shit.

Most students aren’t even organized into any collective organization. If we want mass appeal, and for the majority of people to be able to feel like they have the capacity to affect change, then people need to be organized into something. The YFS is, I think, one place where that could happen. Something many people have been thinking about post-strike is the institutional capacity of 3903. Given the current neoliberal anti-union context, can 3903 continue to amass organizational capacity without completely burning out?

When striking against a multi-million dollar corporate university such as York, unions face a lot of public-relations pushback and questions in the media. What strategies did the university administration employ to sway public opinion and maintain control of university governance in this strike?

Chelsea: We had public opinion on our side in those first couple of weeks. One of the strategic things that we did after the strike vote meeting in March was make sure the membership empowered the bargaining team to go back to the table with York that weekend, before the strike officially began Monday. We drafted a list of key priorities and demands and asked York to negotiate before it was too late. That swayed public opinion because it forced York to publicly say on Saturday that they weren’t coming back to the table, ultimately forcing us to strike.

Our media strategy really came down to a few clear-cut demands: For Unit Two, contract faculty at York, we were going out over six conversions—six $100,000 full-time academic positions. That’s not a lot of money to bring a university grinding to a halt over. And for Unit Three, graduate assistants at York, it was 800 jobs that had been cut by the university when they rolled out a new funding system for graduate students that had the effect of “phasing out” access to union membership and representation, particularly for incoming Masters students. And York made no attempt to restore these jobs—90 percent of Unit Three—despite widespread pushback from 3903 and the YUGSA. As union members we saw this for what it was: union busting.

Susannah: I found the teaching assistant (Unit One) issues—about our work being tied to our funding—were hard to explain to people. I think that we struggled a bit with communicating that in a simple and understandable way.

Karl: In terms of us having public support in those early moments, I agree. But, in terms of the university’s general framing of the strike, I think leading up to and during the strike they successfully framed the bargaining process in terms of what was “reasonable” and “unreasonable” in ways that undermined the union’s legitimacy. They used the fact that we had a sector-leading agreement to say that asking for anything more—in such a climate of austerity no less—was simply greedy and that we were “strike happy.” Then, the university tabled concessions and framed them as reasonable given how advanced some aspects of our contract were. Of course, many of us didn’t fall for this, but I believe the pressure was felt in unconscious ways: we began to whittle down our demands to defend what we’d already won and appear more “reasonable,” all with the hope that this would bring York back to the bargaining table. In hindsight, this was not an effective approach. It’s clear now that York’s strategy was one focused mainly on public relations, attrition, and ultimately, union busting.

Karmah: York spent a lot of time and money to control the messaging of the strike internally. They bought out huge pages in Excalibur, the student newspaper, for months to speak to the undergrad population, who’s already susceptible to being pissed off because they do get screwed over by the strike. And the administration really knows how to exploit that division. In response, we tried to tap into undergraduate grievances with the administration because people already have grievances with York. No one really likes the admin. So we were trying to utilize that. And a lot of information came out to help us in this: the leak of Rhonda Lenton’s lavish expense account and bloated salary paid for by our student fees for instance. That said, we lacked an existing infrastructure connected to the York community. But one thing that helped us when we did get some media attention with the reclamation was to poke a hole in the idea that it’s undergrad versus grad student or contract faculty. We wanted to make the public more aware of undergraduate support.

Chelsea: What Karmah said certainly rings true. I wish that we had spent more time mobilizing the undergraduates in the build-up to being in a legal strike position. I know that we did a ton of tabling and there were some classroom talks, but I wish we had been mobilizing in a way that engaged undergrads to feel like they could participate in the process. What the reclaimers did went above and beyond, and some of the media that was generated by that action was fantastic. It really emphasized the fact that students want a better learning environment, and so our interests can align.

The three-month reclamation of the university’s Senate chamber by undergraduate students was an incredible and radical act of solidarity with the union and union members. What actions did the reclamation inspire? What role did the reclaimers play in the strike? And what were the challenges of maintaining this reclamation?

Karmah: The reclamation inspired a conversation beyond the strike. The strike was a good opening, but the strike and the reclamation built a political atmosphere that allowed us to think about a different university altogether. We were able to mobilize people on issues that are usually addressed in separate ways as separate problems. But we were able to look at the picture as a whole, and we made a conscious effort to connect the issues affecting students today: from tuition, to housing, to mental health, et cetera. The strike exposed a lot of these underlying issues, but the reclamation opened up a real space for discussion. And it even drew in a lot of regular students who weren’t necessarily politically involved. The space opened up opportunities to reach a broader student body and to encourage conversation about the issues that matter to us. The picket lines were a good space for people who knew what was going on, but for people who didn’t necessarily know how to engage with a picket line, the reclamation was another place to go.

We held town halls where anyone that came to the reclaimed student and community chambers was able to directly take part in decision-making about the next steps. We used the space to come together and to come to decisions collectively. In terms of what role the reclaimers played in the strike, the reclamation brought in more community interventions and broader grievances with the university. And we managed to organize beyond the strike including an action downtown as part of Students Against Israeli Apartheid.

On the other hand, the reclamation also exposed some real fundamental issues. Those of us that were involved in the reclamation came to it for political reasons, and we supported the union because the union aligns with our politics. But in terms of trying to expand our reach and influence as the reclamation, we found it difficult to mobilize undergraduates because of the assumption that the union stands against the community. Many undergrads saw the union’s position as being against their interests, not just against the admin. And I think that is not just a result of the university’s propaganda, but also reflects the union’s orientation toward the community and with solidarity in general.

Karl: The reclamation was a huge blow to the university during the strike, and it couldn’t have come at a better time. It gave York another front that they were forced to fight on, at a moment when they were seemingly getting comfortable dealing with our picket lines. The media attention the reclamation received was amazing, not only in terms of the student-based critique that went beyond the university’s failed labour relations, but, like Karmah said, it opened up a place to build political analysis for undergrads and CUPE members alike. It became an organizing hub for autonomous solidarity actions and organized undergrad support for CUPE 3903 actions as well. However, as a union, there was no formal relationship established with the reclamation: it came down to a group of our members doing solidarity work and forming relationships on a more individual level.

This was a big missed opportunity. As a union, we benefited from the reclamation, but we didn’t make good on our side of the relationship, which could have been a very dangerous alliance (for the university). Instead, it fell upon a core group of individuals in the union to cultivate solidarity with the reclamation, which ultimately was a thankless task. Because the relationship with the reclamation was never formalized or deepened in a sustained way by CUPE 3903, many issues arose in terms of accountability and mutual support. I hope we can learn from this experience as a union because the only way to win in the future is to actively build solidarity and not take it for granted.

Chelsea: Coming off of a big win in the 2015 round of bargaining, we really missed a chance to cultivate strong solidarity networks at York, and we had fantastic opportunities to do so. Rhonda Lenton becoming president of the university with no transparency: that was something that the cross campus alliance organized a bit around, but we should have demonstrated against it. There should have been multiple speaking events; we should have done a lot more to establish stronger networks. And what we saw with the reclamation was how weak those networks already were.

What important tactical and organizational lessons have you learned from the strike, and how should this experience inform bargaining in the future?

Chelsea: As always, it’s important to learn from this experience, something we also did coming out of the 2015 strike and moving into this latest round. In 2015 the “eighth line” 2 was such a mess, and getting people paid was such a mess, which led to a lot of really intense internal conflicts. But with the way we approached the 2018 strike, you can see how we learned from the past. The eighth line ran better, and we had a pay system in place from day one. So what can we learn from in this instance? If we’re going to picket for weeks and then be legislated back, and the university (or any employer for that matter) feels no real pressure to bargain with us during that time because they know we’re just going to get legislated back, what do labour disruptions look like moving forward? Not just at York, but for the labour movement as a whole? How do we move past just the picket line into something that’ll actually increase pressure to the point that it gets an employer back to the bargaining table? A lot of what we did on the ground at 3903 pushed the limits of what CUPE National would consider picketing. Why are unions like UNIFOR, CUPE, OPSEU, and CAUT sitting on million-dollar strike funds when the ability for strikes to have an impact is being legislated away?

We need to talk about these strategic questions, but we have to make sure that we protect our allies and members from all reprisals across the board, and, if they aren’t, we have access to funds to make sure they’re protected and compensated. Otherwise, how can we ask people to do this work?

Karl: There are certainly lessons to be learned, but it’s also a new context moving forward. Not only in the education sector, but across the board we see employers increasingly emboldened to take a “zero bargaining” stance and wait for either the union to cave or the government to step in. We saw that with the Canadian Union of Postal Workers, we saw that with Air Canada, and we’ve seen that in our case at York. And we’re going to keep seeing this pattern because it’s largely worked so far for employers under both Conservative and Liberal governments. It’s a curious thing because, reflecting back on the strike, so much of what we did in the early weeks and months was all directed at getting York back to the bargaining table. In retrospect, they were never coming back, no matter how much we lowered our bargaining proposals and ramped up our actions. This makes me wonder what we could have redirected all that ultimately fruitless energy towards. They way I see it, in the future, there could be two ways to go about this.

On the one hand, I wonder if we could have redirected all that energy inwards, to actually start deepening our relationships amongst our members and bring in increasing numbers of union members who were otherwise not invested in the strike. I wonder if we could have worked to build our base as the strike went on, and therefore gain in resolve and numbers the longer it continued. This might seem paradoxical, to get stronger as a strike goes on, but doing this internal work would have put us in a much different position. If York could have seen us build our base and grow our numbers as the strike went on, they would have been less confident to just wait us out.

On the other hand, and here I agree with everyone else, if we could have escalated our job actions and built power to be more disruptive during the strike, we could have used escalation as a tactic to actually strengthen our position at the table or coax our employer back to the table, where the employer becomes scared almost of what our members are capable of if they don’t show some semblance of movement. There were moments of that in the 2018 strike, but I think we need to break free from our fixation on picket lines, which have become almost status quo at this point. We need to become more militant in how we put pressure on the university administration.

Chelsea: It’s hard to look back. No one expected the York admin to do what they did, to stubbornly bring the whole university into a protracted fight for 143 days before ultimately getting what they wanted with back-to-work legislation. It’s just clear that they’re not bargaining, so we need to prepare people for this reality, to protect ourselves from their punitive responses, and to move beyond a merely reactive position in relation to York and its bargaining team.

Karmah: Clearly, the fact that York was willing to do what it did and destroy themselves and their reputation means they have a long-term plan. If somehow by some magical force, the whole community was on board with shutting down the campus and you actually had not only students’ sympathy but real student support, I don’t think they would have been able to do what they did. I do remember something specific from the strike: the first time that the Liberals were about to legislate 3903 back to work, a few professors, some of the reclaimers, and other community members met to discuss what we could do despite our small numbers. And we were really planning on a wildcat strike, with hard pickets everywhere to shut down the campus and to see how long we could last. Obviously, that’s not what ended up happening, but we were trying to actually build our capacity to do a large-scale solidarity action. Imagine having more support from bigger labour organizations like CUPE National to do this work. Just think about what we’d be capable of if we could compensate people for this kind of work. To extend that work to the community and to support the community; that would be great.

Karl: I’ll echo again that we need to think beyond the picket line. We’re stuck in a bit of a rut with traditional legal actions being the norm, where people are most comfortable. Unfortunately, that’s also where employers are most comfortable too. At York, due to the nature of our employment as teachers and TAs, we’re not only withholding our labour from the employer: we’re withholding our labour from our students as well. That puts us in a unique and complicated position when it comes to striking and running picket lines. It’s a tough line to walk to both withhold your labour from the university and express your support for your students. We attempted to make this connection with the expression, “Our working conditions are your learning conditions.”

The fact that York has added two subway stations on campus has also changed how we thought strategically about striking. Direct, on-campus subway access means our picket lines have become much less effective. This made it easier for York to brazenly keep classes open despite the ongoing strike, therefore encouraging scabs to continue working (which is not an issue if the university is forced to cancel classes due to picket lines). This new context sends a strong message that our traditional picket line strategy that has worked in the past will not work in the future. In spite of this, we did our best to shift our strategy, and we lasted 143 days doing so. But outlasting the university is clearly not a battle we should choose again, because as Chelsea and Karmah have said, York has shown a willingness to go full self-destruct in order to wait us out and have the government step in for them. It’s time we got more creative, more disruptive, and more unpredictable in when, where, and how we strike against York in the future.

Susannah: With all these critiques in mind, we also shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that we held a strike for 143 days—the longest strike in post-secondary Canadian history—which is in itself a success despite being legislated back to work and forced into arbitration. From an organizing perspective, holding eight picket lines and mobilizing hundreds of people for that long of a time is impressive. It has the effect of strengthening the labour movement, building a community of new labour activists, and politicizing students and workers. And my hope is that it will have long-lasting effects in ways that we don’t even know yet, that we can’t delineate right now, but that we’ll see in the struggles to come. *

Notes