The Ground Beneath Our Feet

Commoning In, Against, and Beyond the Mechanisms of Urban Accumulation

We are sitting in Prinzessinnengarten, a 6,000 m2 garden adjacent a busy roundabout in the heart of Kreuzberg, Berlin, during our regular Commons Evening School. Behind the fence, a large construction site with three towering cranes looms overhead: construction is underway on “The Shelf,” a hub for tech-companies willing to pay astronomical rents. It is one of many in a cohort of developments by Pandion, a prominent real estate shark—astute in artwashing techniques—operating in the city. We meet here every Monday evening to learn and unlearn together through the processes taking place in the garden, collectively forming an agenda that is both hands-on and theoretical. We explore the opportunities and challenges of commoning and the ways in which we can contest the mechanisms of the commodified and speculative city, specifically the mechanisms of temporary use. We discuss, we listen, we go on excursions to other places facing similar struggles, they come to visit us and share their experiences, we water plants, we compost, we get our hands dirty cultivating the land. On this particular Monday, a feminist-activist group working together with refugee women—to create workshops and support structures for sharing the knowledge and skills necessary for navigating bureaucratic procedures—joins us to discuss holding workshops and festivals in the garden, and we enthusiastically discuss plans. This is one of the invaluable aspects of the garden: alongside the everyday activities of gardening, bee-keeping, and the bike repair workshop, it is a space where groups from various social movements—ecological, anti-racist, feminist, or broadly anti-capitalist—can hold talks, film screenings, workshops, and festivals in the shared laube (arbour) space, fostering alliances between multifaceted struggles. After the group leaves, however, a degree of somberness sets in as we confront the current insecurities: the temporary use rental contract expires at the end of the year, a part of the garden has decided to move elsewhere, and the demands that we have put forward in dialogue with the governing bodies—for a long-term lease or permanent protection of the space—remain unmet. A few weeks later, we host a “deep mapping” 1 workshop in the garden where we explore the perceptible as well the less registered relationships and meanings of the garden, within the broader city context, in space and time. One of many aspects and questions that arises from this exploration is: why should we pay rent for public land that is commoned as an open space? On the other hand, if this garden is just one social space in a city that is facing unprecedented rent increases and displacement, why fight for this site when there are so many other threatened spaces, some of which are people’s homes, their basic material security?

The word boden in German has a very symbolic and powerful double meaning. It denotes both the soil, in a very material sense, and the ground, something that has become semantically abstracted through commodification. In the face of devastating ecological destruction, the soil from which life grows is perpetually enclosed, exploited, and destroyed. At the same time, the ground beneath our feet is being continually privatized and speculated upon so that large real-estate companies can extract money from that which sustains life, both ecologically and socially. The natural world is displaced for large-scale exploitative production; we are displaced from our homes; we are displaced from our remaining social/ecological spaces and local neighbourhood businesses. These threats we face to our everyday lives, our social fabric, and our natural world appear so big, so beyond our ability to change the course of history. But we, together, pose a counter-power—through different imaginations and different practices of our everyday and social lives, through defense and creation—on this ground, with these feet, these hands, these bodies. We cannot act from nowhere. We need somewhere to place our feet, to grow roots in the soil. Together we can defend and create life. Prinzessinnengarten is more than just one place: it is a place where life continues to grow from the ruins of “business as usual.” To fight for and steward this ground is both concrete and symbolic. It is rooted here, but the branches stretch out in solidarity, struggle, and strategy to fight for all vulnerable social-ecological spaces, all threatened spaces necessary for our everyday subsistence, all spaces where life grows in, against, and beyond the commodified and speculative city. We start here, but we do not stop here. This situates practices and spaces of commoning within a broader struggle against the capitalist (re)production of space and for de-commodified and emancipatory spaces in the city where we can come together across differences to explore different ways of thinking, feeling, doing, and being in common. It situates these practices within, against, and beyond the qualitatively evolving displacement enacted by capital as it usurps urban/rural space, and the lives and labour of those who (re)produce it in the pursuit of endless economic growth, recognizing that a predatory relationship to land, and those who inhabit it, cannot be severed from capitalism’s origins in historical processes of colonialism. 2

Since the end of 2017, I have had the pleasure of being involved in the Commons Evening School: a self-organized learning community inspired by the work of Paulo Freire. “Liberation,” Freire argues, “is a form of practice: the action and reflection of human beings upon their world with the purpose to change it.” Moreover, he suggests that “the act of knowing involves a dialectical movement that goes from action to reflection and from reflection upon action to a new action.” 3 By engaging in a collective (re)production of our common spaces and natural world, we highlight the often-suppressed experience and articulation of our everyday lives as social and cooperative, delving into questions regarding our alienation from each other, the space of the city, the land, and our own subsistence—under capitalist relations—in order to explore different ways of organizing the common(s). Beyond a demand, spaces and practices of commoning embryonically prefigure 4 alternatives on the ground, situating emancipation in the here-and-now, through means that are not temporally or spatially dislocated from the ends. Through these collective modes of consciousness and practice, we may come to conceive of various social relations and forms of oppression under capitalism—whether gendered, racialized, or economic—not as discrete, spatially and temporally displaced, or cleaved from one another, but rather, as inter-constitutive. This implies that the desire for non-hierarchical forms of being and acting together—against racialized, gendered, ableist, economic, and knowledge-based forms of power and exclusion—are embodied in the everyday practices of sharing, negotiating, and reaching collective decisions about a common space.

Commoning, as a verb, places emphasis on the relational and everyday practices of sharing and negotiation. However, in an urban context, these practices are (re)produced in and against the space and time of the metropolis, confronted with the constraints, the opportunities, and the contradictions it presents. In chorus with Guido Ruivenkamp and Andy Hilton, I and many others

generally avoid the focus on commons as shared resources and rather perceive commons as the creation of new forms of sociality, as new collective practices of living, working, thinking, feeling, and imagining that act against the contemporary capitalist forms of producing and consuming (variously enclosing) the common wealth. 5

The practice of commoning is a constant process of negotiation and sharing, always dependent on people (the commoners), the material/immaterial wealth—and responsibility—to be shared (the common), and, crucially, the space of the city as both “a social product (or outcome) and a shaping force (or medium) in social life.” 6 Commoning, as a collective praxis of reclaiming the right to the city, emerges as a prefiguration of a different sociality and a perpetual process of (re)subjectivation. These new productions of subjectivity, from below and in relation with others—through encounter and negotiation, learning and unlearning, doing and undoing—affirm Harvey’s insistence that the right to the city is “a right to change ourselves by changing the city.” 7

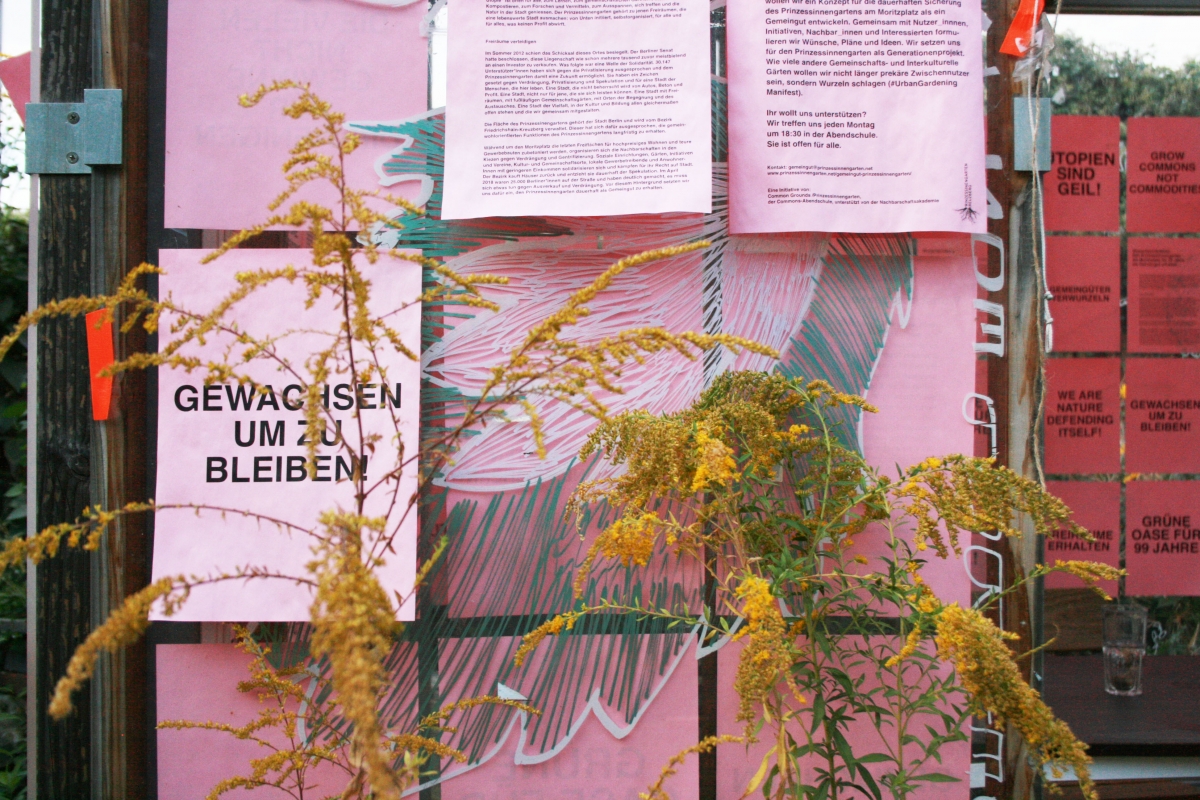

Prinzessinnengarten is one of many communal gardens in Berlin engendered as a catalytic space from the “bottom-up”—to create space for practices of commoning, biodiversity, and experiments in self-organization—in what were once considered urban wastelands. The space was conceived in 2009, after local residents obtained a lease agreement with the borough. However, most of these gardens, or social and cultural spaces, are designated as interim uses and, with increasing privatization and speculation, face an uncertain future. Their allure is captured in city-branding exercises to attract start-ups and investors, while Berlin planning and policy authorities continue to herald praise for temporary use as an innovative and successful urban strategy in the face of staggering displacement of residents, social spaces, and local businesses. The land that Prinzessinnengarten has occupied since 2009 is owned by the municipality. However, it is managed by a city-owned real-estate company that is shrewdly in the business of selling public land to the highest bidder. Regarded as a temporary-use project, and without borough or city level plans to secure its future, Prinzessinnengarten faced the threat of expulsion in 2012 when an investor wanted to buy the area at Moritzplatz. Alongside other vulnerable initiatives in the highly contested area of Kreuzberg, a petition titled “Let it grow!” was launched to bring attention to the insecure future of the garden and other “alternative spaces” of Berlin that had for decades offered free and open space for social, cultural, political, and ecological practices while eschewing the imperatives of monetary profit. This was a dual struggle: for both the protection of these spaces and against the sale of the city. With the support of 30,000 people, they were able to resist the privatization of the area at Moritzplatz where Prinzessinnengarten is located, prompting the transfer of the land from the Berlin Real Estate Fund to the municipality of Friedrichschain-Kreuzberg. This deepened the political aspirations of the garden and the energy generated from the mobilization was transformed into durable forms of praxis: the Common Grounds Association formed in 2013 and the Nachbarschaftsakademie, a self-organized platform for rural and urban knowledge sharing, cultural practice, and activism, began in 2015.

Common Spaces for (Un)Common Knowledge 8

Fast-forward to 2017: amidst continued privatization and exponential rent increases in Berlin, Nomadisch Grün, the not-for-profit entity responsible for many of the undertakings in the garden—including the café that pays the rent 9 —decided they would move to a different site by the end of 2019 when the current temporary-use contract expires. The future of the garden, yet again, seemed to be dangling from a flimsy string: this created a divergence between those leaving and those fighting to secure the site against the mechanisms of temporary use and commodified/speculative space. In the spirit of defending and creating, we started the evening school, and the Common Grounds Association—responsible for the large laube and the neighbourhood academy in the garden—began campaigning for a 99-year leasehold for the undeveloped area of Moritzplatz. Titled the “Wish Production” campaign, we aim to develop networks of solidarity with neighbours, tenant’s initiatives, and other self-organized spaces to not only pose resistance to the mechanisms of temporary use, but also to collectively explore the desires and needs emanating from the garden, as well as the wider neighbourhood context in which those affected live, work, and play. As Marco Clauson writes of the process initiated in the garden:

Tomorrow’s possibilities grow in the gaps of conventional planning processes, nurtured by social desires and needs. At the same time, there is the danger that these places, the movements they represent, as well as the visions, narratives, and terms they create, will be destroyed or appropriated by the process of transforming commons into commodities, alternatives into lifestyles, and poor neighborhoods into gentrified areas. This is why we have to protect them and ask for a different form of ownership: an ownership that does not give us the right to exploit, but the responsibility to nurture and care, the right not to extract, but the stewardship to create “life in the ruins of capitalism” in the hope that also butterflies can create a storm. 10

This dual process of creation and defense is central to the agenda of the Commons Evening School. At a time when, in Berlin, it seems that even transformative claims to, and enactments of, the right to the city will invariably be co-opted, commodified, and harnessed by gentrifying forces, we need ways to resist, together, the institutional/market capture, enclosure, and foreclosure of “bottom-up” or commoning practices. It may be questioned whether a space like Prinzessinnengarten, in a city perpetually gentrified through the co-option of subversive and creative practices, could be seen as contributing to such patterns. These patterns can render us feeling impotent when we reflect on ways of prefiguring practices of commoning and ecological regeneration in a manner that can subvert co-option and the spiraling patterns of gentrification and displacement. This, I believe, is the urgency of aligning practices and spaces of commoning with a broader struggle against the systemic issues created by the capitalist (re)production of space. We need de-commodified and emancipatory spaces in the city—for us and our non-human-others—where we can come together across differences to explore practices of sharing, different ways of thinking, feeling, doing, and being in common. We need to create and defend these spaces, and we need to defend them in chorus with all other fights against the capitalist city. To this tune, members of the Commons Evening School have collectively participated in various movements and protests across Berlin, large and small: from the mietwahnsinn (rental madness) demonstrations to a direct action taking place against our neighbouring Pandion site, organized by a large group of artists that came together to form a network of solidarity posing refusal and resistance to the art-washing techniques of gentrifying real-estate companies.

In this light, the Commons Evening School could be understood as a common space for (un)common knowledge. (Un)common knowledge refers to subjugated knowledge: knowledges from the peripheries and the depths, knowledges that de-center power and hegemonic capitalocentric, anthropocentric, patriarchal, and white/Western discourses. While these practices of commoning and (un)common knowledge-making seek to subvert imposed identities and uneven relations of power, they are not exempt from missteps. Reflexivity is central to ensure that enclosures do not form around homogenous communities. A question we often raise and one that we are actively trying to address is the creation of formats and activities in the garden—such as free family-friendly movie screenings, neighbourhood cooking nights, and Sunday shared picnics—that decisively move beyond a nominal openness towards an actualized and inviting openness. To this end, during a recent neighbourhood assembly in the garden, we were confronted with a misstep that had been overlooked: a woman brought it to our attention that large parts of the garden were inaccessible to her wheelchair, something that we needed to address. As Stavrides implores—counter to dominant institutions that reinforce inequality by establishing hierarchies of knowledge, decision-making, action, and claims to rights 11 —we must connect commoning with processes of opening:

opening the community of those who share common worlds, opening the circles of sharing to include newcomers, opening the sharing relations to new possibilities through a rethinking of sharing rules and opening the boundaries that define the space of sharing. 12

There has been a conscious decision to ensure that the current struggle and the Commons Evening School are grounded in the German language to ensure we do not alienate those who do not speak English, even when English can at times be a more common medium amongst a diverse group of native- and non-native German speakers. However, it requires a careful balancing act not to, in turn, alienate those whose mother-tongue is not German. To address this, people are encouraged to vocalize questions and opinions in whichever language they feel more confident. This is an ongoing process of reflexiveness, one that must constantly reckon with various forms of unintended exclusions that can emerge even in the pursuit of defending an inclusive time and space.

The “Wish Production” campaign has incorporated more traditional tactics, such as flyer distribution and dialoguing with politicians, but it has also drawn on creative modes to frame dissensus. 13 Spaces of commoning inherently tend to embody a dissensual nature in the city. Rancière suggests that fictions, as creative modes of framing dissensus, can reveal new relationships between appearance and reality, allow for different ways of sensing, and foster new forms of political subjectivity: “It is a practice that invents new trajectories between what can be seen, what can be said, and what can be done.” 14 In this spirit, the campaign has adopted creative modes to reveal the forces at play in the city, contest them, and carve different imaginaries and practices for the city as our collective oeuvre. For example, a workshop titled “Speculative Real Estate/Speculative Fiction” invited people to join us in imagining a future scenario whereby Prinzessinnengarten and other social spaces had lost their lease to the predatory speculative practices of real estate companies. Through a format of collective storytelling, we identified pressing issues in the Mortizplatz area to build fictional realms through which we could explore the problems, needs, dreams, and possible trajectories to be taken.

Fictions as a Mode to Frame Dissensus

Storytelling and sharing have also been mobilized to highlight that these struggles are not contained in a specific space nor in a specific time: they are both trans-local and trans-historical. Beyond the neighbourhood in which Prinzessinnengarten is situated, similar fights can be observed throughout Berlin as well as in other urban and rural contexts. Many activities in the garden have reflected on these struggles. People from the ZAD in Western France, 15 where one of the largest prefigurations of commoning grew from the activist practices that halted the planned construction of a mega-airport, came to the Commons Evening School to share their struggles and learnings. Patrick Kabré presented a documentary and discussed SolAir Silmandé, an artistic-gardening project in Silmandé, Burkina Faso. The summer program of the Nachbarshaftsakademie included a screening of the documentary Chão, about the Brazilian Landless Workers Movement (MST), followed by a discussion with MST representatives, and various events on socio-ecological justice in Brazil have reflected on expropriation of Indigenous Amazonian lands. All of these mutual exchanges have helped to situate the localized micro-political struggle for Prinzessinnengarten within a broader sequence of, and in solidarity with, trans-local articulations of, and struggles for, the common(s). In fact, Moritzplatz, where the garden is located, is also a site of historic struggle: in the 1960s, a major highway was planned for the area that would cut through one of Europe’s densest neighbourhoods and displace its residents. It was the resistance of the neighbourhood that prevented this and other forms of displacement via urban renewal. By constructing a historical timeline of the various struggles connected to the site and elsewhere, we sought to transcend the singular and local to create passages that could connect these historical memories with the present and the future. Additionally, two members of the Common Grounds Association worked alongside an alliance of urban gardens in Berlin to create a proposal for the permanent protection of these socio-ecological spaces in the city. Taking inspiration from the “Tenure Treaty to Protect the Berlin Forests”—introduced to safeguard Berlin’s nature from deforestation and construction after widespread resistance to the destruction of the Grunewald forest in the early 1900s—the “Tenure Treaty for Berlin Gardens” advocates for the permanent provisioning and protection of these spaces for commoning and the common good.

What does it mean to practice spaces of commoning, spaces and times in which our logics do not correspond to the external logics that we encounter in non-egalitarian and capitalist circuits of daily life? Spaces like Prinzessinnengarten embody vulnerable tensions within the logics of the city: the logics of property, of accumulation, of dispossession, of violence. How can we enact such spatial practices in, against, and beyond capitalism without becoming fodder for the co-option of added “cultural value” and its resulting accumulation by dispossession? How can a space like Prinzessinnengarten be defended, but as more than an enclave of emancipation? How can we conceive of an over-spilling and radiating beyond confined boundaries or new forms of enclosure? This critical positioning of commoning within but also beyond the notion of sharing, both material and immaterial, situates it as a process of negotiation, one that cannot shy away from inherent antagonisms. 16 Considering that spatial practices of commoning are reproduced vis-à-vis the normalizing order of the metropolis, we must locate the qualitatively evolving processes and mechanisms of capitalist-state governance and urban development patterns hostile to the common(s) to subvert them.

Primitive Accumulation as Process not Historical Fact

John Holloway employs the term “form-process” to present a new reading of Marx’s concept of primitive accumulation, something that Holloway argues, along with the corresponding enclosure of common land and the conversion of our human creative doing into paid labour, cannot be considered a foreclosed historical concept. 17 Rather, it is a constant process of separation: from that which we collectively produce and sustain through encounter, negotiation, and cooperation. As Holloway states, “it is not just a question of the creation of new private property… the old, past, established property is also constantly at issue. Even the property of land enclosed three hundred years ago is constituted only through a process of constant reiteration, constantly renewed separation, or enclosure.” 18 Here, we could return to the question that arose during the “deep mapping” workshop in the garden: why should we pay rent for public land that is commoned as an open space? As Kirkpatrick Sale remarks, contesting the fragility of structures we have come to accept as irrefutable, “owning the land, selling the land, seemed ideas as foreign as owning and selling the clouds or the wind.” 19

Here, we cannot bypass the important work of Silvia Federici—who visited the garden last year and discussed the current situation with us—on the enclosure of the commons, which occurred simultaneously alongside the enclosure of women’s bodies and colonial exploitation. Building on this seminal work, she has also explored the new enclosures, emphasizing the continuity of enclosure and accumulation throughout capitalist development. Rather than categorize accumulation as a “one-time historical event,” “it is a phenomenon constitutive of capitalist relations at all times, eternally recurrent.” 20 Federici draws on, challenges, and departs from Marx and Engels’ hypothesis that capitalist development would provide the material conditions for socialized production and distribution. Rather, she posits that, in the drive for endless accumulation, capitalism unleashes a relentless destruction of our natural world, communal spaces, and mutual relationships. 21

At a time when local authorities, urban researchers, and practitioners have heralded temporary use as something to be incorporated, developed, and harnessed, we must engage in a critical interrogation of this mechanism in processes of accumulation. The fall of the Berlin Wall and de-industrialization created a new aggregation and surplus of space, which, at first, alleviated West Berlin’s housing shortages and engendered many informal spatial practices. However, it was quickly accompanied by the rampant privatization of public goods. This process was further fueled in 2001 with the collapse of a city-owned bank, Berliner Bankgesellschaft: privatization, at an ever-greater speed and scale, was employed to service the 6 billion euro banking debt. 22 Large speculative real-estate companies, such as Deutsche Wohnen, took control of the city’s housing and other building stock. In response to excess supply, authorities and land owners employed the tactic of temporary use to “revitalize” vacant building stock and land. This process, alongside continued privatization and city-branding exercises, led to increased property values. 23 As Madanipour explains, for producers, temporary use is “an opportunity to fill some gaps, utilizing and increasing their assets” while, for the majority of temporary users, “access to space at a low cost, which would not be affordable otherwise, constitutes this opportune moment, facilitating experimentation and developing new capacities.” 24 This opportunity, once seized, is often absorbed into a desirable social trend, a trend that is far from innocuous. As we are witnessing in many cities around the world, it has also contributed to processes of (re)accumulation: when the interim use vacates, the spaces tend to be filled by enterprises willing to pay significantly higher rents due to the increased cultural value that has been syphoned from the uses temporarily occupying the spaces. And with this, we have seen the onslaught of displacement that ensues. Nowhere is this more pertinent than in the case of Berlin, where rents skyrocketed an unprecedented 70 percent between 2004 and 2016. A 1m2 patch of Prinzessinnengarten land now has a market value of €5500.

Temporary Use as Mechanism for (Re)Accumulation

How do we reconcile this phenomenon of gentrification with the contingent spaces of commoning—such as Prinzessinnengarten—that emerge in the gaps, the footholds, and vacant spaces? In fact, an experimental temporality is often inseparable from the emergence of many spaces of commoning. As Doina Petrescu from the architectural practice AAA explains, they often work to reveal the opportunities for inhabitants to occupy and transform disused urban spaces into common spaces, collectively re-appropriating and reconfiguring these immediately accessible spaces in the city according to their needs and desires. They can also act as sites of learning by which the situated knowledge-making can be transmitted to other locations and different projects, even when the project itself may only be temporary. 25 Moreover, as Stavrides implores, inventive practices of urban commoning, or “spaces-as-thresholds,” can “acquire a dubious, precarious perhaps but also virus-like existence: they become active catalysts in reappropriating the city as commons.” 26

We should not hastily abandon temporality and experimentation. However, we must find opportunities to enact other ways of doing and being in the city, when and where we find space to do so, while being rigorously aware of our place in urban development patterns. Returning to Holloway, he reminds us that within the form-processes of enclosure and accumulation we can also situate a present, everyday struggle: a “live antagonism.” 27 The spatial practices of urban commoning not only respond to immediate necessities and desires; they also enter the “live antagonism” and contest the normalized metropolis, finding and enunciating possibilities to negotiate, subvert, refuse, and act-otherwise. The activities of the Commons Evening School and the Common Grounds Association in Prinzessinnengarten presents us with a concrete example in which people are coming together, entering the “live antagonism” to contest the mechanisms of temporary use without degrading the temporal and unfolding nature of commoning, calling for the permanent provision and protection of social, ecological, and political space. It is a demand for the durable de-commodification of space to foster a “liminal space which invites liminal practices by people who experience the creation of potentially liminal identities.” 28

While most of these urban gardens and social spaces in Berlin emerged informally—when, where, and how they could—many are now refusing quiet acquiescence when forced to reckon with the mechanisms of temporary use. This is a reflexive positioning that has grown out of the exhaustion that accompanies temporal insecurity inasmuch as it has from the recognition that temporary use is contributing to urban patterns of accumulation. Instead of walking away, people are mobilizing and fighting to stay, and to grow, in solidarity with their vulnerable neighbours. I by no means want to present a rose-tinted image: a space like Prinzessinnengarten has at its disposal a certain leverage due to its prominence in the city. It is also not a simple feat. These spaces require sensitivity to foster alliances. Fighting for free and open social spaces may seem like a trivial pursuit to someone facing the imminent threat of losing one’s home. It is critical to convey that when we are fighting for these spaces, we are not only fighting for social-ecological spaces: we are fighting for spaces of solidarity and the radical sharing of power against and beyond the accumulation and enclosure of that which we collectively produce and sustain—of our commons.

Conclusion

When we fight for our rights to the city in chorus, we are fighting for the wholesale de-commodification of the city, for the right to housing, for the right to the city as our oeuvre, for the right to liveable lives, and for the “right to change ourselves by changing the city.” It is not an attempt to erase differences and tensions but to carve a space for collective exploration in and through these differences and tensions. As Stavrides implores, “commoning … may become a force to shape a society beyond capitalism so long as it is based on forms of collaboration and solidarity that de-centres and disperse power.” 29 By critically reflecting on the opportunities and contradictions posed by the contemporary metropolis, we may begin to carve tactical and strategic trajectories for our praxis. And, in doing so, we can reckon with and counter a hypothesis that our spatial practices of commoning—of carving out free and social space, space for our everyday lives and social reproduction—will struggle to emerge as more than pawns in capitalist co-option and result in the displacement of our neighbours and ourselves. This hope is a strategic hope. It is one that acts with a critical understanding of the forces at play in our city. It is the hope of creating and defending. Fragmented, we fall prey to capital accumulation. Together we pose a counter-hegemonic project of negation-creation-defense. *

Notes